Share this story

- While teacher attrition may not have been as bad as some thought last year, it is still a problem for many districts. Find out who is hardest hit and what teacher attrition means for schools.

- "Somehow, someway, as a state, we’re going to have to make sure that we’re showing these individuals that we do value them," said Polk County Schools Superintendent Aaron Greene. Find out how teacher attrition is affecting districts.

The State of the Teaching Profession report presented to the State Board of Education in March suggested that fears about a mass resignation of teachers due to COVID-19 may have been overblown. The catch was that the report only covered last school year and many educators suspect next year’s report will say something different.

And, while the number of teachers leaving the profession may have only ticked up a little — from 7.53% in 2019-20 to 8.20% in 2020-21 — the number of teaching positions open (vacancies) in districts ballooned from 1,646 to 3,216.

The state Department of Public Instruction (DPI) District Human Capital Director Tom Tomberlin said in an email shortly after the State Board meeting that without further data it is impossible to say what was happening with vacancies in 2020-21.

“We don’t have the data to know if the current vacancy rates indicate a higher percentage of the total number of positions in the state,” he said in an emailed statement. “It is possible that LEAs are hiring more teachers with ESSER funds and the increased positions are raising vacancy rates.”

“LEAs” stands for Local Education Agencies, which is mostly another term for school districts. “ESSER funds” references Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief federal funds given to states to help deal with the impact of COVID-19.

Find an overview of the presentation to the State Board here.

Notable overall state attrition numbers

The number of teachers statewide leaving for “personal reasons” fell about 15% from 4,039 to 3,449. Overall, 44.6% of teachers who left the profession in 2020-21 said they were doing so for personal reasons.

This was the biggest category of teacher attrition, and can include things like family responsibilities, health, continuing education, family relocation, resigning to teach in another state, or just generally being dissatisfied with teaching. Perhaps related to the pandemic, there was a roughly 2% increase in the number of teachers leaving the profession due to “family responsibilities/childcare.”

The percentage of teachers who left the profession due to retirement also ticked up about 5%. In 2020-21, almost 20% said they left for this reason.

And, while still relatively small — about 1% of total attrition — the number of teachers who died in 2020-21 was up 16% from 2019-20. Sixty-four teachers died in 2019-20 compared to 74 in 2020-21.

Roughly a quarter of the attrition falls into the category of “other” or “unknown” reasons.

What do things look like at the district level for attrition and vacancies?

DPI measures attrition at both the state and district level. Below we list the top five and bottom five districts when it comes to teacher attrition at the district level — which DPI defines as “the combined effect of teacher attrition from public school employment and the mobility of teachers across LEAs.” Here is the data from DPI we used.

Districts with the highest attrition rates:

- Northampton County Schools — 35.7%

- Washington County Schools — 25.0%

- Caswell County Schools — 24.4%

- Weldon City Schools — 23.8%

- Polk County Schools — 23.0%

Districts with the lowest attrition rates:

- Elkin City Schools — 3.5%

- Clay County Schools — 4.3%

- Surry County Schools — 6.9%

- Macon County Schools — 7.1%

- McDowell County Schools — 7.1%

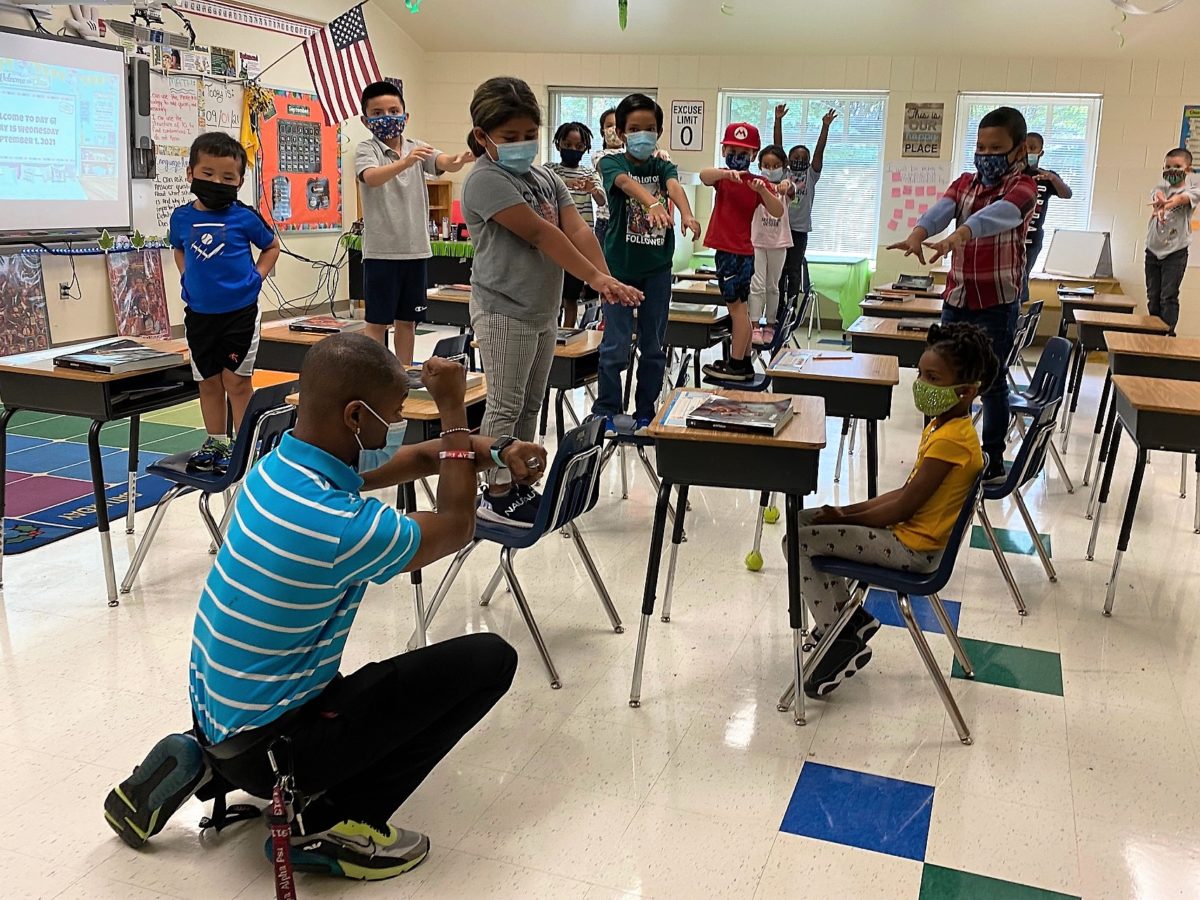

Districts were asked on both the first and 40th day of school during the 2020-21 school year to report vacant positions. K-5 schools had the most vacancies in the state: 690.6. (It’s important to note, however, that there are more K-5 schools than other types of schools.) Career technical education (CTE) was second-highest with 272.5.

The vacancy data below (from the State of the Teaching Profession report) is based on what districts reported on their 40th school day.

Districts with the highest teacher vacancy rates:

- Bladen County Schools — 22.6%

- Anson County Schools — 15.2%

- Thomasville City Schools — 13.5%

- Person County Schools — 13.0%

- Vance County Schools — 12.8%

Districts with the lowest teacher vacancy rates:

- Polk County Schools — 0%

- Graham County Schools — 0%

- Rowan-Salisbury Schools — 0%

- Buncombe County Schools — 3.5%

- Henderson County Schools — 3.7%

What do district leaders think?

Aaron Greene is the superintendent of Polk County Schools, which has the fifth highest teacher attrition rate in the state at 23%. He said that his district has traditionally had an attrition rate lower than 10%.

He attributes that to a number of things, including the departure of the baby boomers from the teacher ranks. But, he said, there is also the way teachers have been treated during the pandemic.

“At the beginning they’re the heroes, and then by the end they’re the scapegoats,” he said.

And competition from South Carolina is also a factor.

“Educators can make a significant amount more by literally driving five or six miles,” he said.

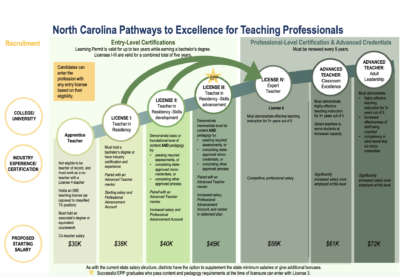

Washington County Schools has the second highest attrition rate in the state. Linda Carr, the superintendent, lays the blame in part on how some teachers are trained in North Carolina. A residency license allows people who have met certain requirements to start teaching while they are still working towards full licensure. Carr said that creates difficulties.

“The newly-hired applicant, is having to work full time, often raise a family, return to school to complete additional studies and commitments to keep the job all while trying to keep up with the latest trends and demands in education handed down by the state and the local public school unit,” she said in an email.

She said that residency candidates can’t do any of these tasks “at an optimum level” and the candidate is always in “survival mode.” This puts the district at a disadvantage if they have to rely on these kinds of candidates. (“Residency” is the new name for what was once called “lateral entry,” which is when people from other fields make a transition to teaching.)

“As a school system we are unable to move forward due to always circling back (and) training the newly-hired employee due to high turnover rates,” Carr wrote in the email. She calls the current issues she is seeing the worst they have been in 28 years.

Of course, not everyone is impacted the same.

Myra Cox is the superintendent of Elkin City Schools, which had the lowest attrition rate in the state at 3.5%. She attributed that low number to the fact that teachers simply like working in her district.

“I think they feel supported, and I believe that they are here to serve our students to their fullest capacity,” she said. She also noted that during the pandemic she felt like teachers were holding on out of concern for their students during a stressful time.

But Cox also admitted that competition from neighboring districts isn’t as strong as it might be for some other superintendents — if her district was closer to Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools or Guilford County Schools, for example, she said things might be different. She also noted that her district is able to offer teachers a 5% pay supplement.

But Travis Reeves, superintendent of neighboring Surry County Schools, feels differently. Surry County Schools had the third lowest attrition rate at 6.9%, but Reeves said he is only able to offer a supplement of about 2.7% on average, and many of his neighbors, like Elkin City Schools, can offer at least 5%.

“One things we pride ourselves on is supporting our teachers, both just from the granular side of administration, but also from the side of curriculum support,” he said, adding later: “Teachers want to feel supported. Teachers want to know that their principals are organized and are running a … good school.”

And what about vacancies? The number of vacancies in the state jumped pretty dramatically during the pandemic.

Greene said he has noticed a big change since COVID-19.

“We would put out an elementary opening and before COVID we would get 20, 30 or more applications,” he said. “Now we’re getting like four or five.”

Reeves said his district has had trouble filling positions all year. Surry County Schools has tried many strategies, including asking retirees to come back and work, having teachers cover extra classes, using virtual teaching, and increasing class sizes.

“You can’t manufacture a math teacher that can teach AP statistics,” he said. “Those are hard-to-fill positions.”

When it comes to coping with these issues, many districts are trying something to help keep or attract teachers. Greene said his district, for example, is trying to do a better job of marketing itself. But what would really help, he said, is if the state found a way to show teachers some love.

“It’s not a day care job or a babysitting job. These are professionals who have a lot of education, who have a lot of expertise and skill,” he said. “Somehow, someway, as a state, we’re going to have to make sure that we’re showing these individuals that we do value them.”