Share this story

- Up to 44% of college students report symptoms of depression and anxiety, and suicide is their third leading cause of death. Read more about how North Carolina colleges are addressing mental health.

- “As we emerge from the pandemic and build momentum for a great comeback, the mental health toll that faces our students will need to be addressed," @NCCCSPresident Thomas Stith said.

Upward of 44% of college students report symptoms of depression and anxiety, according to a 2021 report by the Mayo Clinic Health System, and suicide is their third leading cause of death.

These “alarming statistics” were presented by North Carolina Community College System (NCCCS) President Thomas Stith at the UNC System’s virtual 2022 Behavior Health Convening last month. The event, sponsored by NCCCS and North Carolina Independent Colleges and Universities, was hosted March 30-31 to discuss ideas and best practices for supporting student mental health across the state.

“Supporting the mental health of our students is paramount to their success,” Stith said at the conference. “As we emerge from the pandemic and build momentum for a great comeback, the mental health toll that faces our students will need to be addressed.”

North Carolina is ranked 42nd for its quality of youth mental health, according to Mental Health America’s 2022 State of Mental Health in America report.

More than 14% of North Carolina youth, 110,000 of 12- to 17-year-olds, experienced a severe major depressive episode, the report says. Nearly 52% of North Carolina youth with major depression did not receive any mental health treatment.

Colleges must prepare to meet such mental health needs, conference speakers said. They can do so by providing accessible mental health resources, faculty mental health training and financial support for students.

“Our students are in dire need of your support,” Stith said. “And it will take a statewide unified effort to gain ground on the significant impact that mental health is having on the future leaders of North Carolina.”

The multi-session seminar featured leaders from across the state, including state Secretary of Health and Human Services Kody Kinsley and Nash Community College’s Marbeth Holmes.

Here are some highlights from the convening.

Impact of the pandemic and need for funding

Early in the pandemic, the number of North Carolinans who reported experiencing symptoms of depression or anxiety increased from one in nine to one in three, Kinsley said in a presentation about the state’s pandemic response. That increase disproportionately impacted younger populations, he said.

Among college students specifically, presenter Brett Scofield noted the pandemic’s wide-reaching impact on mental health. Scofield is the co-interim senior director at Penn State University’s Center for Counseling and Psychological Services. He’s also the executive director of the Center for Collegiate Mental Health (CCMH), a research network of over 650 colleges.

Scofield highlighted an increase in nearly every category of self-reported distress at college counseling centers in the last 11 years, with the exception of hostility and substance use. During the 2020-21 remote learning year, reports for visits due to anxiety and depression stayed relatively flat from before COVID-19. CCMH data shows reports of social anxiety were down. Reports of academic distress, eating concerns and family distress all increased.

The demand for college counseling services increased across the board.

“When you have an increase in demand for services without concurrent support to find those services,” Scofield said, “counseling centers have to shift models.”

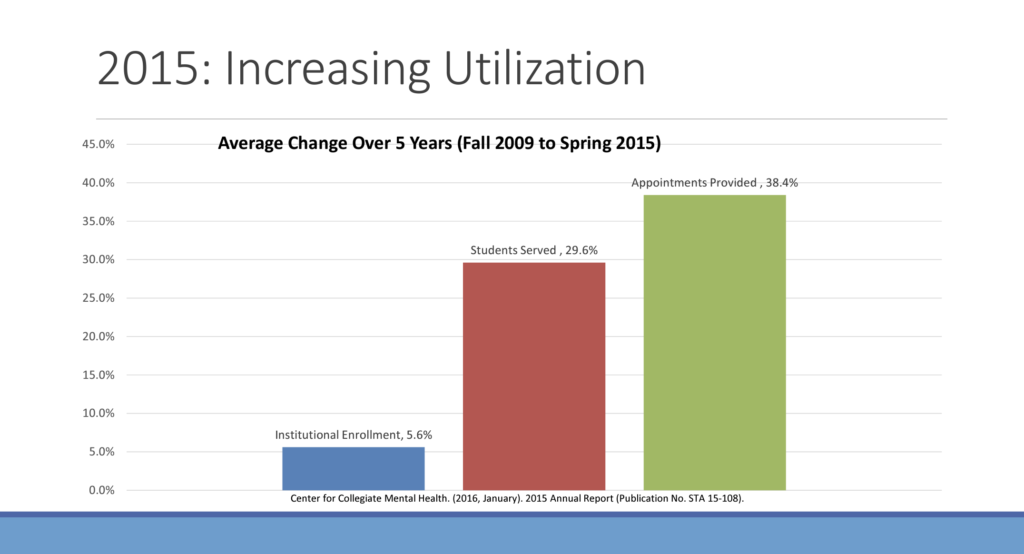

From 2009 to 2015, for example, institutional enrollment among the 100 analyzed colleges increased on average by 5.6%. The number of students served by counseling centers increased by 29.6% during the same time period, and appointments provided by 38.4%.

As a result, counseling services increasingly devote resources to rapid access and brief interventions, while routine counseling decreases.

“Faculty, staff, students, families, administrators in the university have an expectation of what the counseling center can do that is well beyond probably what they’re funded to do,” Scofield said. “Mental health in higher ed is described as a crisis, but we think the crisis is the capacity to treat them — not necessarily the number of students that are seeking services.”

Secretary Kinsley also spoke about funding during his presentation, noting the importance of investing financially in behavioral health.

At the start of the pandemic, more than 1 million North Carolina residents lacked health insurance — a statistic Kinsley said Covid exacerbated, and one that continues to impact statewide access to mental health care. Kinsley didn’t have health insurance until after college, he told attendees.

“My experience of not knowing how to navigate getting a doctor or finding a doctor,” he said, “those conversations are very much real experiences that over 10% of North Carolina’s population have today.”

![]() Sign up for Awake58, our newsletter on all things community college.

Sign up for Awake58, our newsletter on all things community college.

Kinsley also noted the “unprecedented impact” Medicaid expansion would have in closing the mental health coverage gap.

Currently only low-income workers, low-income people with children and people with disabilities qualify for Medicaid, along with pregnant pregnant people during their pregnancy and for 60 days after giving birth.

North Carolina is one of only 12 states that has not taken advantage of Medicaid expansion, North Carolina Health News reported in March, though a bipartisan committee in the state legislature is studying the possibility of expanding Medicaid. That expansion would allow households with an income below 133% of the federal poverty line to qualify for coverage.

Edgecombe County Public Schools found a way to use Medicaid reimbursement to offer social worker services to every student in its alternative learning program, EdNC reported last month.

“If we’re going to make a meaningful difference in our mental health and substance use disorder challenges, we have got to have Medicaid expansion,” Kinsley said. “Because without dollars for care, we’re only treating people in crisis. And if we’re only treating people in crisis that we have already lost the battle.”

Building a mental health tool kit

Beth Rice, the social and emotional learning (SEL) lead with the Department of Public Instruction’s Office of Educational Equity, gave a presentation on building a mental health tool kit.

The tool kit focused on Pre-K and K-12. Guidance for colleges centered on how to incorporate SEL into teaching programs.

The presentation defined SEL as “a strengths-based, developmental process that begins at birth and evolves across the lifespan. It is the process through which children, adolescents, and adults learn skills to support healthy development and relationships. Adult and student social and emotional learning competencies include self awareness, self management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making.”

School mental health: Comprehensive school mental health systems provide a full array of supports and services that promote positive school climate, social emotional learning, mental health, and well-being, while reducing the prevalence and severity of mental illness.

All learning is both social and emotional, Rice said. Research shows that integrated SEL approaches lead to academic achievement, and can close opportunity gaps and mitigate mental health challenges.

“North Carolina is ranked 42nd,” she said in reference to Mental Health America’s 2022 report. “So we have a lot of work to do.”

SEL isn’t often a part of college curriculum, but mental health first aid training for faculty can help students. Stith said the N.C. Community College System is currently investing in such training.

Other colleges partner with local providers to support students. Forsyth Technical Community College, for example, refers grieving students to Trellis Supportive Care in Winston-Salem, a local hospice organization.

Shifting focus from stigma to resources

Many mental health campaigns emphasize reducing the stigma around mental health.

While such messaging “certainly can’t hurt,” Daniel Eisenberg with the research institute Healthy Minds Network said student mental health investments must go beyond that.

“The solution to an increase in health seeking is going to have to go beyond just providing awareness and outreach, beyond educating students and making them more aware,” Eisenberg said. “For many individuals, there has to be something more that we do to facilitate it.”

At Healthy Minds Network, discussion about such efforts focuses on integrating mental health care into what students already do. One example, Eisenberg said, could be adding a brief mental health assessment or referral process to already-required academic advising sessions.

Marbeth Holmes, the dean of student success at Nash Community College, said part of investing in student mental health is addressing barriers related to education, health care and food. At community colleges, 20-40% of students face food insecurity, she said, and 50% are housing insecure.

In a “rural resource desert,” like Nash County, Holmes said the college must prioritize meeting basic needs among its students. She noted that such needs disproportionately impact Black, Latino, Native, first-generation, disabled and LGBTQ+ students.

“The most important thing we do in that process is advocate for the students,” Holmes said, “and then follow up.”

In 2014, Nash Community College implemented its Culture of Blue Love student program. The Blue Love fund provides Food Lion and Walmart gift cards, meal vouchers and transportation assistance. It also helps students facing eviction, utility disconnection and “catastrophic events.”

The school also offers a variety of wellness and academic assistance programs. Use of those programs led to higher semester completion rates, Holmes said, as well as higher grades.

Since starting Blue Love, Holmes said she increasingly tells students to “come back anytime, because you know I love you.” That culture is empowering, she said, and something Covid forced the college to lean into more

Most important to Holmes, Nash Community College works to build relationships with students — something she said all colleges must do to effectively meet mental health needs.

“We work very hard to build trust,” Holmes said. “If they trust us, they will utilize our services. If they utilize our services, their work and their stability and their wellness will improve — so that’s fundamental.”

Recommended reading