Share this story

- .@ClevelandCC hosted a prison-to-community simulation, highlighting the challenges incarcerated individuals face once they're released.

- More than 20,000 people are released from North Carolina prisons each year. Their reentry into society is marked by transportation issues, financial strains, and roadblocks to employment and housing.

- Studies show that both educational training and work release programs significantly reduce recidivism rates among those formerly imprisoned.

Each year more than 20,000 individuals are released from North Carolina state prisons and return to their communities. Roughly 95% of those incarcerated in the state today will be released. But the reentry process for this vulnerable population is challenging.

Imagine being asked to secure housing, transportation, forms of identification, clothing, food, and employment all within a short period of time. What would be considered an arduous task for most is even more difficult for incarcerated individuals being released.

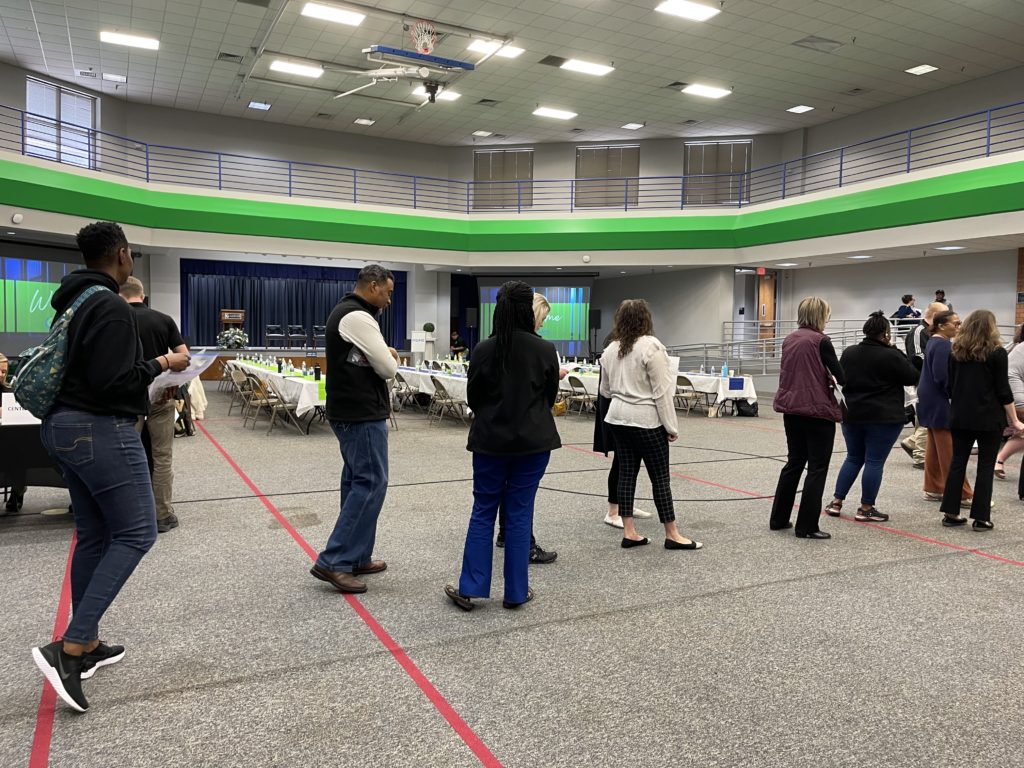

To illustrate these challenges, agencies and organizations across the nation conduct reentry simulations to show communities what recently released inmates come up against as they transition back into society.

On March 30, the North Carolina Department of Public Safety (NC DPS) led a reentry simulation at Cleveland Community College. The event, “In Their Shoes: A Prison-to-Community Simulation,” was sponsored by STI Fabrics and included participants from community colleges, resource agencies, local industries, judicial districts, community corrections, and chambers of commerce.

Stepping into their shoes

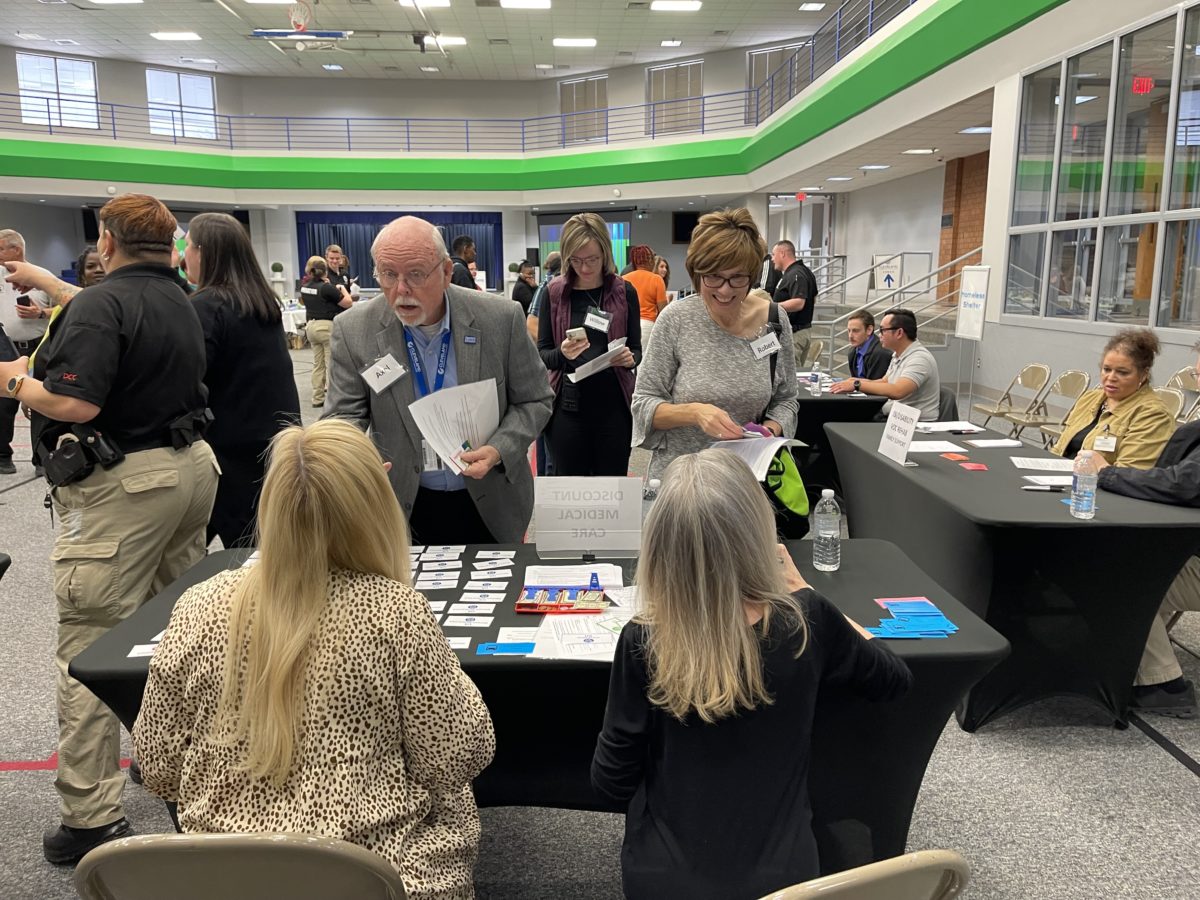

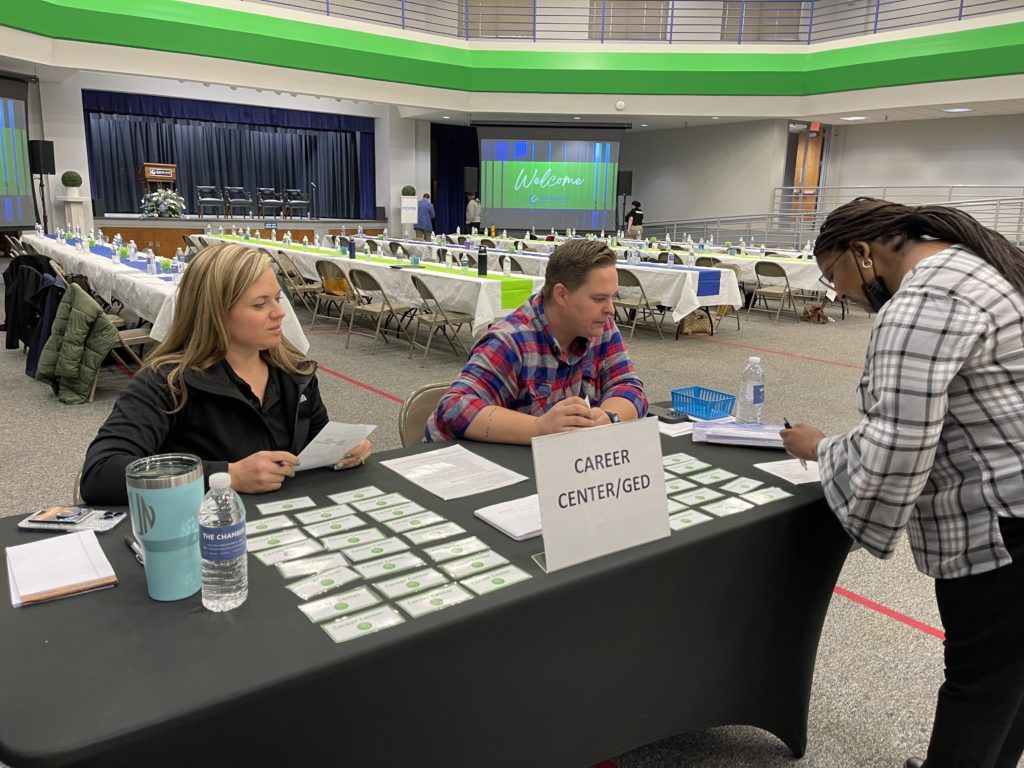

The simulation lasted one hour in a space that was designed much like the community a formerly incarcerated individual may experience upon release. Each table represented places someone recently released may need to visit — from the DMV to a career center to a food bank.

Before starting, participants were given a bag at random. The bag contained their identity, the crime committed, educational level, and forms of identification. Other details included their housing, financial, and employment situations.

Using the information made available to them, participants had 15 minutes to complete their assigned tasks. Each 15-minute interval was the equivalent of one week. Tasks included securing housing, a job, transportation, identification, and food.

Moving from each station required one transportation ticket – something that many participants said proved difficult because they lacked the financial resources to purchase the ticket.

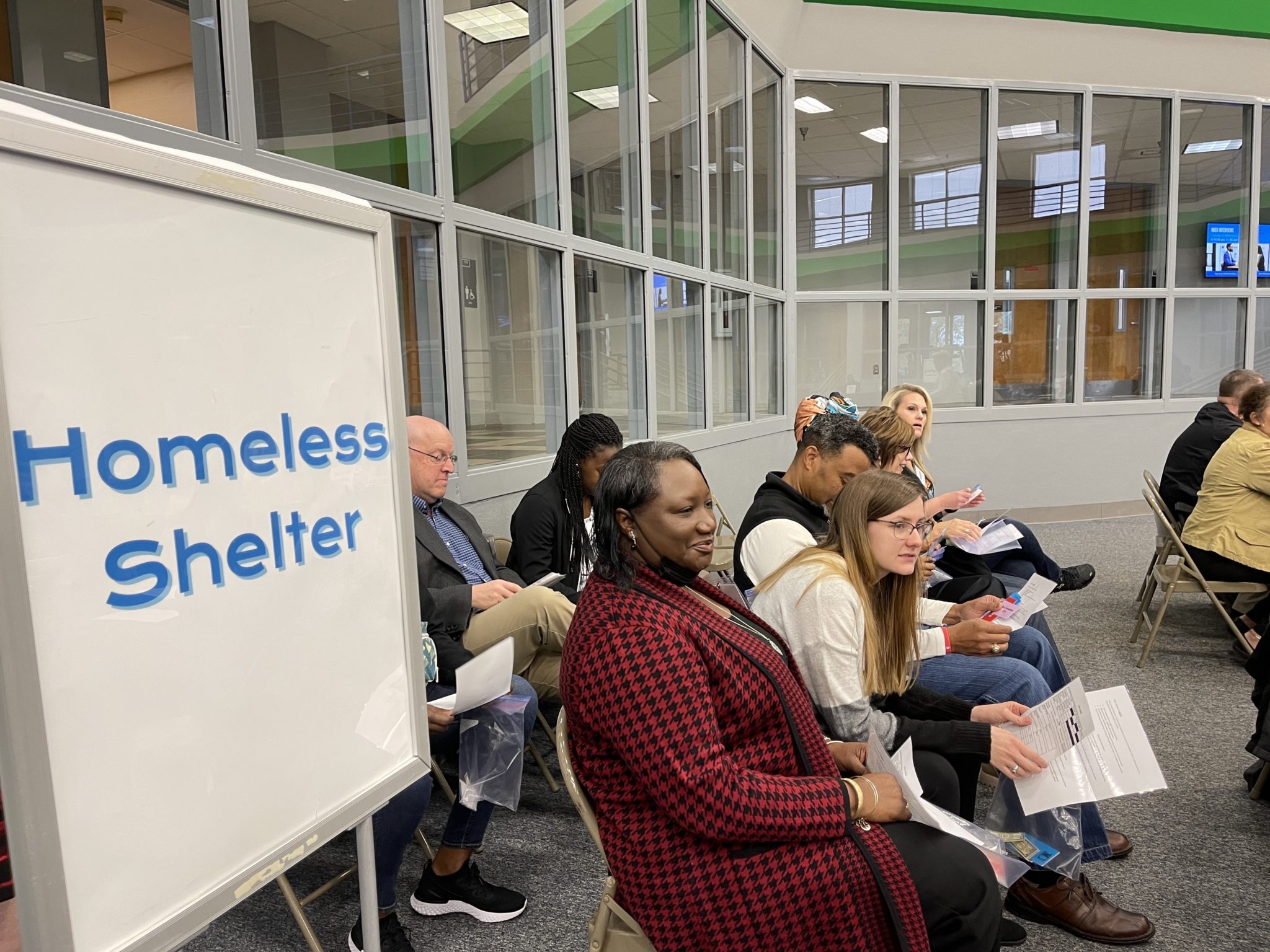

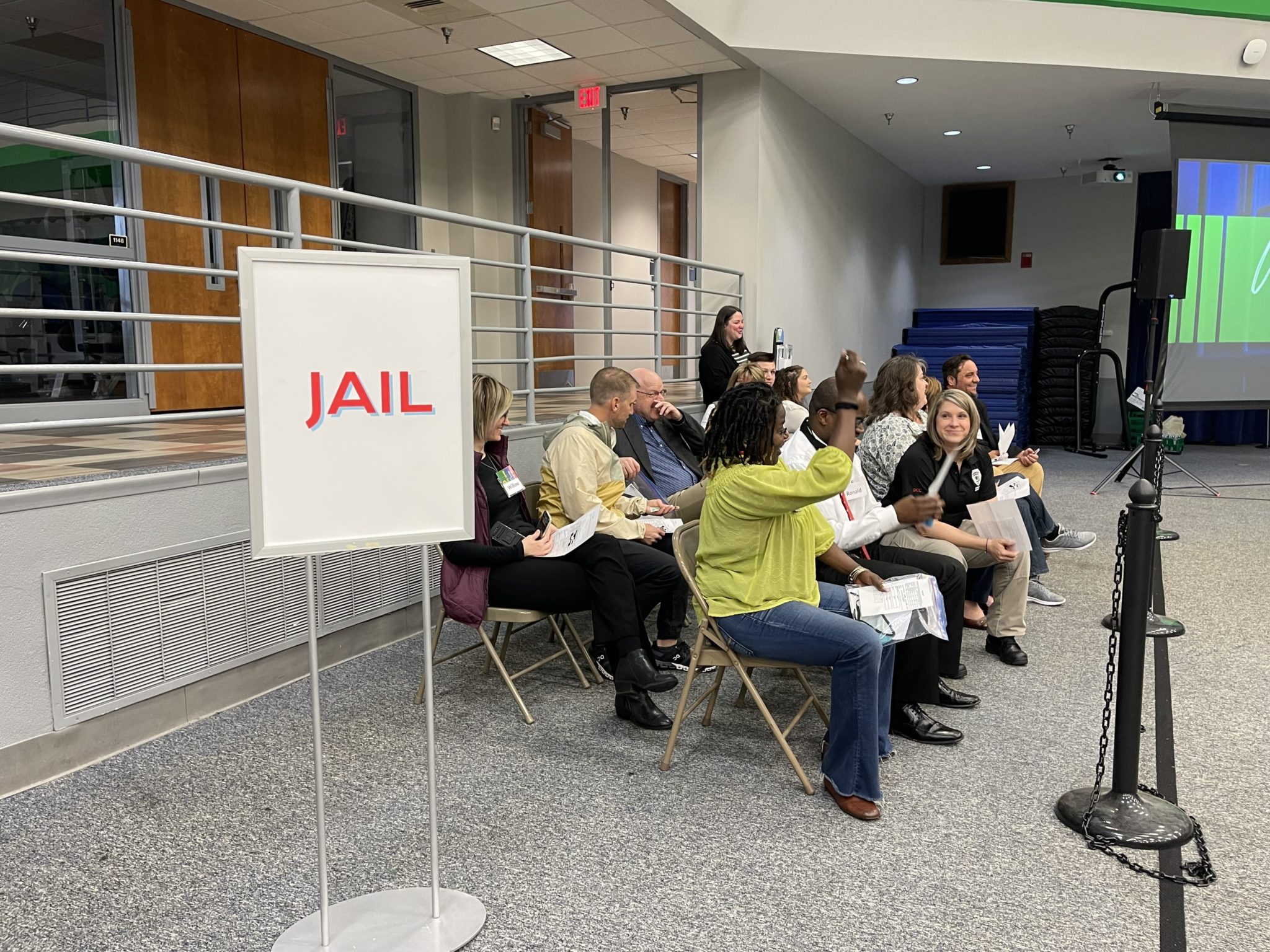

Failure to complete even one task on the list meant participants risked going to a homeless shelter, half-way house, or back to jail. In some instances, a participant would make it to the correct station only to receive a card that said, “You are five minutes late to treatment and cannot enter” or “There are no jobs available right now.”

The long lines, unexpected bumps in the road, and navigating an unfamiliar system left participants feeling overwhelmed and frustrated.

Many said it shed light on the struggles formerly incarcerated individuals deal with once released. Others said they understand why someone may choose to reoffend.

“When people get frustrated, they go back to what they know,” said Jennelle McCorkle, reentry officer for NCDPS.

A reentry plan from day one

Successful reentry starts well before an inmate is released.

There are two prominent initiatives in North Carolina aimed at reducing recidivism and creating positive transitions: work release and educational training.

While in prison, inmates can earn a variety of credentials, including high school equivalency and career and technical degrees.

A 2013 meta-analysis by RAND Corporation concluded that inmates who participated in educational programs had 43% lower odds of recidivating. And the odds of obtaining employment after their release increased by 13% among those who participated in educational programs.

Cleveland Community College is one of 41 community colleges in the state to provide educational training to inmates.

When the college gained ownership of a prison that closed in 2009, they were able to make significant upgrades to the facility that houses four educational programs.

The college serves prisoners from Lincoln Correctional Center in Lincolnton. Inmates enrolled in the educational programs are transported from Lincolnton to Cleveland where they receive training from college instructors. The education they receive is identical to that of a traditional community college student.

Once a prisoner completes the one-year program, they earn a certificate from the college. According to Brandon Ruppe, director of customized training at Cleveland, the inmates also receive a National Center for Construction Education & Research (NCCER) certification, which is a nationally recognized trade credential.

During the March 30 event, Dr. Jason Hurst, president of Cleveland Community College, announced a new name for the prison program at the college. The educational training program is now called I.M.P.A.C.T., which stands for Inspire and Maintain Personal Achievement with Constructive Trades.

Like educational training, the work release program provides certain incarcerated individuals an opportunity to be employed in the community while still imprisoned.

Inmates involved in the work release program have lower recidivism rates than the overall prison population. A 2015 report showed the recidivist incarceration rates among work release participants was 34%, while rates of those not in work release was 47%.

Inmates who participate in the work release program are screened and selected by prison managers and must be in their final stages of imprisonment. They are required to earn at least minimum wage, and their earnings are used to pay fines, family support, prison housing, and work release transportation costs. Inmates also have the opportunity to save money for when they’re released.

Sandra Jenkins, human resources manager at STI Fabrics, shared her company’s experience with work release during the reentry simulation.

STI started working with Gaston Correctional Center in 2019 to offer jobs to inmates through the work release program. According to Jenkins, the company has employed around 40 inmates. Some began to work full-time after their sentences were over. STI currently pays inmates $15 an hour.

When asked what employers who are considering the work release program should know, Jenkins said the program is an opportunity for businesses to hire individuals who want to work and have reliable transportation every day. Jenkins also said employers are not in this alone. She said there are others who have gone through this process and are willing to help companies start their own customized program.

“Offenders are released every day into our communities…We can either choose to be proactive in a positive way or wait to be reactive.”

Sandra Jenkins, human resources manager for STI Fabrics

What’s next for reentry?

As early as 2009, efforts have been underway in North Carolina to reduce barriers for those reentering society after incarceration. In 2017, the North Carolina General Assembly and Gov. Roy Cooper doubled down on the state’s efforts. The General Assembly established the State Reentry Council Collaborative (SRCC) which is responsible for providing recommendations to reduce barriers and help those reentering find resources. Cooper requested that a Reentry Action Plan be created to improve the transition from prison to community.

By 2019, the first-ever reentry summit convened to discuss the barriers faced by those returning to their communities after prison.

In 2020, Cooper signed an executive order to implement fair chance policies at state agencies and increase employment opportunities among those with criminal records. The full order can be found here.

The SRCC continues to hold meetings. A final report with their findings and recommendations is here.