|

|

Lauren Cappola knew she was sounding repetitive, but she felt compelled to ask the same question of her colleagues everywhere she went across the state: How are you connecting children with the mental health services they need?

As director of counseling services for Harnett County Schools, and a former counselor herself, she saw that the need for mental health services was clear — but so, too, were many barriers. Services outside the schools aren’t widely available in her area, and many school families lack transportation or insurance.

“I kept hearing the same thing,” she said. “We found a lot of people contracted outside services, which is a roadblock for us because there’s not a lot of agencies to contract with, and then you have to stay in a certain catchment area.”

Contracting with outside providers has worked in other places, such as Transylvania County. But Harnett is larger, with businesses and residences spread out. The school system didn’t have a lot of success with this model, Cappola said.

One day, she spoke with a colleague from neighboring Lee County, which had built a system-wide team within its central office that could provide those outside services inside school buildings.

“She was so excited,” said Jermaine White, the district’s assistant superintendent for student services, “and I thought, why can’t we try it. It just took an idea, we put some action behind it, and this is where we are now.”

The result is a five-person mental health support team that works directly with students in schools to provide mental health services that just two years ago lay outside their grasp. Student referrals, student treatment, and teacher knowledge have all gone up, White said, and the district continues to improve on this idea — most recently adding an art therapist to the mix.

First step: Navigating funding and personnel issues

The program began with the 2019-20 school year — just before the COVID-19 pandemic. At that time, the most visible roadblocks involved staffing and getting students to their referrals.

“There would be so many mental health needs of our students, but then there wouldn’t be enough therapists or any appropriate referrals for them,” said Jessalyn Pedone, the first mental health support specialist on the team. “So there were a ton of kids that just weren’t getting the service they needed.”

Some exhibited behavior issues at school. Others started isolating. Some stopped showing up for school at all.

“We were all working overtime trying to really help them and support them as best we could,” Pedone said. “But I think that, unfortunately, there was only so much we [could] do.”

When the district decided to build an in-house team, two issues arose: finding the personnel and paying for them.

White had to get creative with the budget. He didn’t want to build a new team with grant money because he worried about sustaining it. Instead, he found vacancies the district didn’t need to fill, and he reallocated those dollars for the mental health support team.

When the district asked Pedone to join the team for the 2019-20 school year, she jumped at the chance. As a social worker, she was trained and licensed to offer one-on-one therapy and trauma support. But ethics rules prevent school social workers from offering all their capabilities to students.

Following the model from Lee County, though, when Harnett County Schools established the team it restructured Pedone’s social worker role as mental health specialist, allowing her to provide all of the services for which she is certified.

Finding talent outside the county

As Pedone and a former district staffer began the project, Cappola and White worked on expanding the team.

Statewide, public schools are below national recommended ratios for social workers, counselors, and psychologists in schools. Part of the problem, historically, is lack of funding. Another part, White said, is finding local talent.

The district hired Christi Lowe from a district in Virginia and Jenae Cox from a mental health agency that served Orange County Schools. Initially, the district hired Lowe and Cox as social workers. Neither knew about the program when they were hired.

But Lowe was already feeling hamstrung by the ethics rules, and Cox was feeling sick over the number of students she was signing up at her outside agency who still weren’t receiving treatment.

“You see the need every day, and for me, I’m like, I know I can do it — but I can’t,” Lowe said. “So this was just so exciting to be able to join the team, and be able to do it.”

Cox added: “I was one of those outsourced therapists that was school-based, so our goal was more getting bodies rather than actually helping. Having the clients and making sure you have that huge caseload, but being unable to actually be effective, I just needed something different. They gave me a chance here. Thank God.”

Last year, Lowe and Cox joined Pedone to form the specialists team, with Heather Baumhauer providing mental health support, and Amanda Sambets serving as a facilitator. They’re all stationed at different base schools, with the three specialists splitting the county into thirds and the others floating. Each specialist serves seven to nine schools.

What services look like

Social workers and counselors identify students who may need services, making referrals to the mental health support team once a parent consents to treatment. Then the team, which includes the behavioral support lead, decides at its Friday meeting whether it will take the case.

Approval criteria for the program include such things as access and capability. If students, for example, have insurance to cover treatment and transportation to get to it, they might be good candidates to refer out. The district also refers out students whose needs fall outside the team’s scope of practice.

“But if a student isn’t approved for the process, that doesn’t mean we’re just going to kind of let them go to the wayside,” Pedone said. “We are very comprehensive, and so we want to make sure that we’re giving them whatever referrals are needed, helping them get to where they need to go.”

When the team decides to take a case, the specialists find appropriate times — outside of core courses — to meet with the student at school or via video conferencing. It simplifies things for families.

“Some parents would take off half days or whole days to make it work right, and so kids are missing a lot of instruction if they went to a weekly therapy appointment,” Cappola said. “Now we can provide that, and then they get right back to class.”

Teachers also get more interaction with specialists, helping build relationships. That rapport has helped create buy-in when specialists offer training, White said.

“I think when you sit around and listen to every one of our people talk, there’s a passion behind it which makes the difference,” he said. “You can’t not have the passion and do this right, because it’s going to become mundane and you’re not really going to put the effort into it.”

Adding art therapy, and who knows what next

White hired Sambets before the school year, getting her from the Wake County Public School System, where she taught exceptional children. Before moving to North Carolina, though, Sambets lived in New York, where she became licensed as an art therapist.

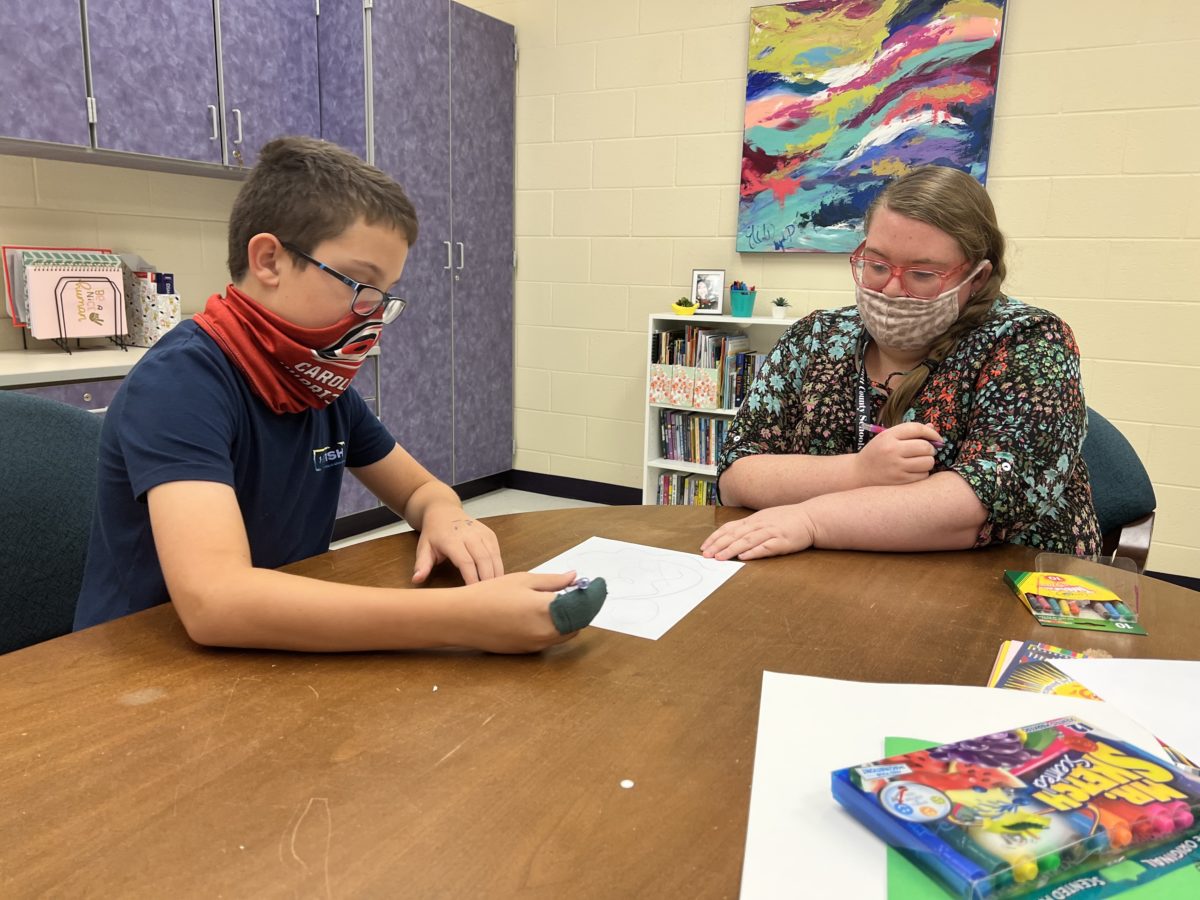

You hear a lot about art as therapy, or music as therapy. “Art therapy” is something different. It’s a clinical evaluation and treatment of students through art projects. Sambets connects with kids while they draw, putting color and shapes on a canvas while pulling stories and thoughts and feelings from their heads.

The support team says art therapy has been an added layer of support and, particularly for younger students who may not have the language for what’s happening to them, has provided a unique service.

Sambets watches carefully as a student draws, noting things like the sharpness of peaks in the triangular shapes and the overuse of straight edges. All of it tells her something about what’s going on in the child’s mind.

“And then from there, I can come up with a treatment plan,” she said. “Things will come out and I can say, OK, this is what we need to work on.”

Sambets also leads group activities. Last month, for instance, she partnered with one of the family engagement specialists to lead a grief group activity for students at one of the district’s dual language immersion schools during Hispanic Heritage Month. She helped students create an el duende painting. El duende means a heightened state of emotion, and the process usually means layering paint on a single canvas over a six-week period. These students worked on the art for two weeks.

North Carolina doesn’t yet recognize art therapy as a licensed profession, but the mental health support team has found ways to use Sambets’ skills in multiple ways to help students.

“So [the specialists] created a partnership where a student might be referred and then they go through a process where we staff [the student],” Cappola said. “We talk about their needs and their interests and things that may work for them, and then she works with one of these three ladies to integrate the therapeutic art services.”

Changing attitudes toward mental health support

White likes to talk about the many layers to the new project, but one he keeps coming back to is the foundational piece of weaving mental health supports into everything the district does.

“Sometimes people, left to their own devices, think that if they give a worksheet or give a talk about it, that that’s enough to address mental health,” he said. “Well, there are so many different things that we can do as a school system to improve people’s attitudes towards getting [students and teachers] assistance that they need. And that was missing here.”

Now, with outside service capabilities brought in-house, layered on top of what social workers and counselors provide, more students are actually receiving services, Cappola said. Plus, teachers are getting consistent consultation and training on best practices.

“I think the beautiful part about it is, as we’ve gone through this process and people are kind of catching on to this being a component of our school district, they’re less fearful to ask questions when they don’t know,” White said. “What’s been outstanding about this is that I start hearing people use more of that technical terminology and it’s clearly because they’ve been communicating with the people who do this, and they’re getting an understanding and want to know more about how to help these kids.”

The program’s success has White and Cappola thinking growth — again.

“Our vision is for us to have three times as many of our mental health support specialists to serve our district,” Cappola said. “We want to grow this. We want this to be desirable for qualified clinicians to reach out and say, ‘Hey, I want to come and I want to work here and I want to be part of this because it is amazing.’”