|

|

There are plenty of reasons for a school district not to try new things on top of all the changes of the last two years of pandemic schooling. Yet when Erin Swanson heard of an opportunity to rethink Edgecombe County Public Schools’ approach to early learning, she knew that finding new ways to meet students and families’ unfilled needs was worth it.

Edgecombe joined a cohort of five districts pulled together in 2021 by The Innovation Project and the Friday Institute through an initiative called the Early Learning Network, funded by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. The network facilitated design-thinking sessions that focused on challenges and opportunities in early learning.

“I’m sure it feels right now like, ‘Oh my gosh, how could we add one more thing?'” said Swanson, assistant superintendent of innovation and strategic planning for the district. “I think for us, we’re like, ‘Gosh, if we don’t, then we’re going to be in the same space come five years from now.'”

That space, Swanson said, holds a lot of challenges. The district, like many across the state, has found it difficult to know where children are before kindergarten — and how to support their needs. This school year, the district is trying new things.

The district started with a broad goal that leaders had been thinking about for some time. “We wanted every family to have access to great early learning options for their kid,” Swanson said.

The district was already working to expand its 4-year-old pre-K classrooms to 3-year-olds, but it was running into space and funding obstacles. Swanson’s own 3-year-old is on a waitlist. So, through design sessions and interviews with teachers, students, parents, and other community stakeholders, the district conceived three initiatives.

The initiatives reach outside their own classrooms and schools, to parents, community spaces and partners, to child care providers and to families with children who are not yet in formal settings.

The first initiative is aimed at simply getting everyone on the same page. From health and social services agencies to the district, local Smart Start partnership, and early care and education providers, a lot of programs are trying to serve children and families.

“I do think people are connecting, but I don’t know that we’re doing it in a systematic and comprehensive way,” Swanson said.

The district expanded the role of its early childhood transitions coordinator, Deborah Thomas, to facilitate these connections. Thomas has begun reaching out to partners. In the meantime, the district’s other two initiatives are well under way — early learning pods, which Thomas also oversees, and parent literacy nights.

Pods for 3-year-olds

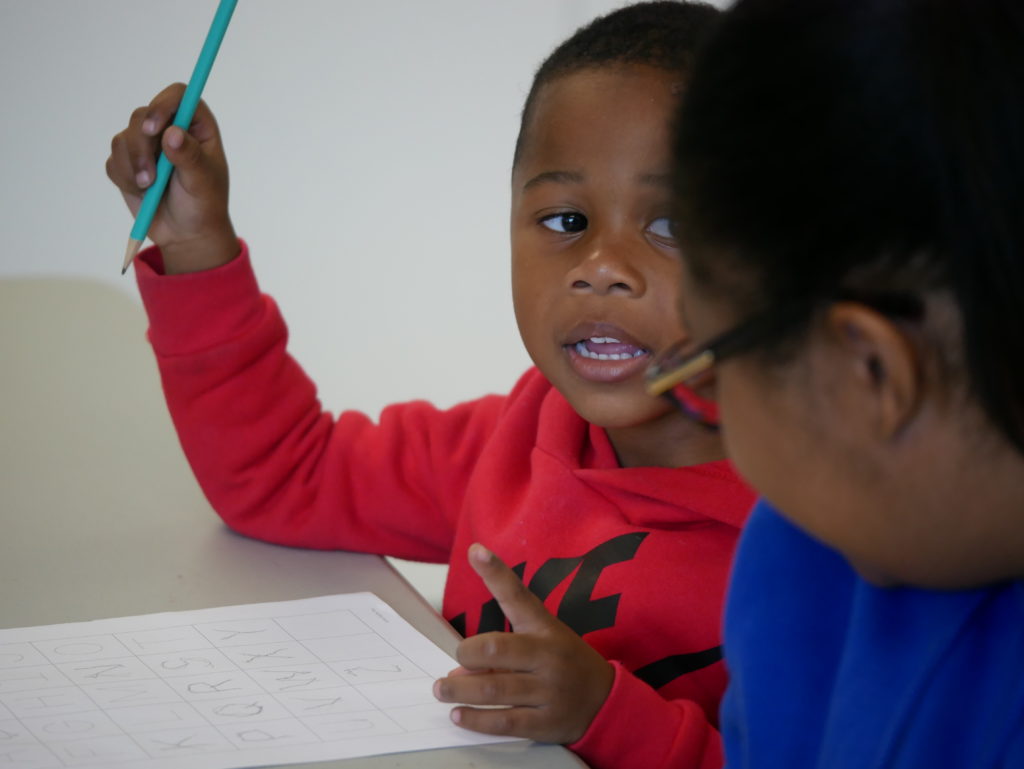

After Alnekia Boone saw what a high-quality early learning environment could do for her daughter when she was 3 years old, she wanted the same for her son, Zaiden.

Unfortunately, Zaiden is on the waitlist for 3-year-old pre-K this year. When Boone saw a Facebook post with another opportunity for Zaiden to learn through the district’s early learning pods, she was immediately interested.

“When he didn’t get accepted into the pre-K program … I saw this and I thought it’d be good for him during the week to try to get him ready next year for school,” she said.

Boone was also excited by the idea of Zaiden getting to interact with children his age.

“He’s with my grandma every day or with a family member for the most part,” she said.

Three-year-olds and their caregivers come to the pods — which Thomas hosts in libraries and community centers — for a couple of hours every week to have story time, interact with peers, do activities, and get a taste of a school setting. Thomas said parents are sometimes confused or intimidated by the term “school readiness.” They often conflate it with an ability to read and perform academic tasks, she said.

Zaiden Boone practices writing letters with the help of his mom, Alnekia Boone. Liz Bell/EducationNC

Carter Height and his grandmother Cynthia Coley learn about shapes and colors. Liz Bell/EducationNC

This weekly time together, Thomas said, is aimed at laying the groundwork for those skills, like familiarization with letters and shapes. But it’s also about developing other simple behaviors parents might not think of: “Let’s learn how to sit down in circle time,” Thomas said. “Let’s learn how to put our listening ears on.”

Having something to offer for children on pre-K waitlists, like Zaiden, was part of the motivation to launch the early learning pods, Swanson said. So was the district’s pandemic experience, when families enjoyed smaller groups in relaxed environments.

On top of that, “empathy interviews” during the design process helped the leaders understand the variety of families’ early learning preferences. Some wanted formal pre-K; some wanted a home-based child care facility; some wanted their children with a family member until kindergarten.

“Hearing from folks what their needs are and their preferences was helpful,” Swanson said. “I think otherwise there could have been this tendency for us to say, great, we have a thousand 3 and 4-year-olds in the district. Let’s try to create a thousand spots in our pre-K program. And that might not meet the needs.”

Thomas said she’s seen the biggest change in Carter Height, who did not speak during the first couple of early learning pods, which started in October. When EdNC visited in November, Carter was interacting with the other children and with Thomas.

Carter’s grandmother, Cynthia Coley, said she’s seen a difference, too. She brought him to the meetings because of his older brother’s kindergarten experience.

The older brother “never went to pre-K or anything, and he’s really behind,” Coley said. “I didn’t want that to happen to Carter.”

‘A community around literacy’

The third initiative, events called “parent educator academies,” is unfolding across the district through a partnership with The New Teacher Project.

The monthly events are intended to teach parents of K-2 students strategies for reading that are supported by research (a body of work often referred to as “the science of reading”) — and to provide a sense of community.

In December, EdNC spent time at a literacy night at Martin Millenium Academy, a K-8 school in the district. It was the second literacy night at the school, with similar nights taking place at elementary schools across the district.

It was also the first in-person event hosted by the district since the start of the pandemic.

“We’re learning something new tonight,” said Terill Adams, a mother of an MMA second grader in attendance among about 50 families. Adams said she attended the first one and came back when she heard this night would include new concepts: phonological awareness and phonics.

“It’s helping me because it’s been a long time since I was 7 years old,” Adams said. “… I don’t know how I learned to read, but trying to do it at home with the way she’s being taught helps me.”

Andi Green talks with parents while they practice reading strategies. Liz Bell/EducationNC

Parents and their children count the words in sentences. Liz Bell/EducationNC

Andi Green, a longtime educator and multi-classroom leader at MMA, went over some concepts like word and syllable awareness with families before they broke into small groups to practice.

Green said she sees the nights as a tool to “lift the capacity” of everyone — children, parents, and teachers — during a stressful transition period for many. The adults in children’s lives are concerned about the last two years of pandemic disruptions: academic, social, and emotional, she said.

“Parents are feeling stressed in thinking that their kids are behind,” Green said. “I think this helps with some of that understanding that your kid is perfect right here … and that we’re going to take them where they are and move them forward.”

Green sends out emails with resources after each meeting and is starting a social media group.

“This feels good,” Green said. “… We are building a sort of community around literacy.”

The first literacy night, focused on bedtime stories (as well as vocabulary building, fluency, and comprehension), had the impact Green wanted on April Best and her MMA second grader.

“It made us want to go home and read a book,” Best said.