|

|

Michelle Chambers was dreading 2022. After a lot of stress, prayer, and family discussion, she had made the call to close A+ Child Care and Learning Center at the start of the year.

“That’s as long as we could hold out,” said Chambers, who has built the Monroe center from the ground up over the past 27 years. The pandemic had left her with no other option.

“We had used pretty much all of our whole savings just to keep things afloat,” she said.

Two weeks later, Chambers read an email about the roll-out of state-administered grants using federal relief money for child care providers over the next 18 months. The news — and the timing — seemed too good to be true.

“I was like, is this a scam?” Chambers said when EdNC visited in October. But once she saw the details, she broke down. “I just bawled,” she said.

The pandemic has put health, financial, and staffing strains on child care providers like Chambers. The stabilization funds will be enough to keep her center open for now, she said.

Yet there were serious financial problems in child care long before the pandemic, and recovery funds aren’t enough to fix them. Chambers was already navigating an industry many describe as a failure of the private market: The cost of care is too high for parents to afford, but not high enough to pay teachers reasonable wages.

Chambers, like other early care and education providers across the state, is in limbo — wondering what’s around the corner while hanging on through ups and downs.

“After 18 months, I’ll have to decide if things are still the same, and if I have to close my doors,” she said.

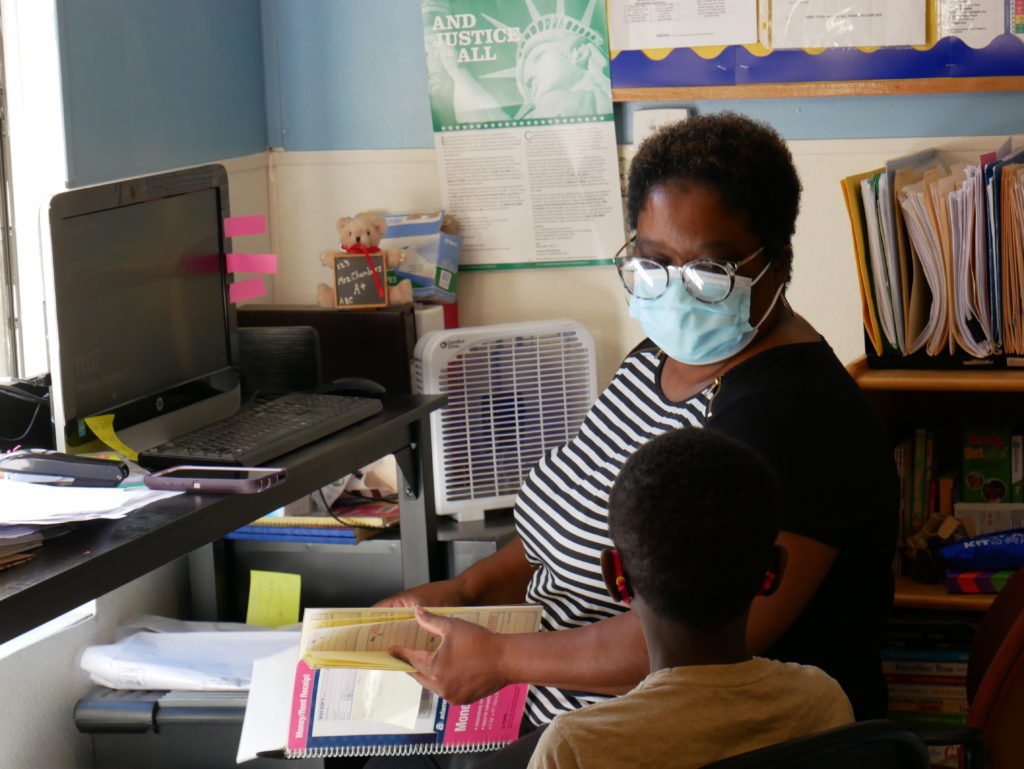

Chambers talks with her grandson, Ayson Selby. Liz Bell/EducationNC

Chambers works in a makeshift office in the same space as one classroom. Liz Bell/EducationNC

‘It’s about families and community’

Chambers’ journey to the child care profession is rooted in a desire to serve her community.

As a behavior management technician in Union County Schools in the 1990s, she communicated with parents about students’ discipline issues. She took pride in creating relationships with children and families. Administrators often would ask her to facilitate conversations and visits because of the trust she had across the community.

Over the years, she said, she started noticing that the doors where she was knocking were those of students who were younger and younger. Chambers was seeing kindergartners “without guidance,” she said.

“I started soul searching,” Chambers said. After talking with her husband, she got up the courage to tell her principal her idea: starting a home-based child care.

“I wanted to reach them and mold them so it wouldn’t be a shock when they went to kindergarten,” she said.

Chambers said she was surprised by her colleagues’ support and the community’s demand. Her original plan was to care for five or so children in her home.

“Then the teachers got involved, (asking): Can we bring our children to you?”

Before she knew it, Chambers had 55 children on her list. She went from operating a home-based facility to a center. She remembers jotting down the phone number for the company that provided trailers to the school district, in search of more room.

Maserasi Tyson, Shonell Jones, and Neveah Tyson get ready for lunch. Liz Bell/EducationNC

Itzayana Diaz and Brittney Gonzalez play during center time. Liz Bell/EducationNC

By 2000, Chambers was serving 78 children. She kept up with changes in the field, earning her bachelor’s degree online from Western Carolina University in less than two years to meet the state’s NC Pre-K requirements. She ensured her center met the staffing and program standards to earn five out of five stars on the state’s rating system.

For the first 15 years or so, Chambers said, she barely had teacher turnover. “All my teachers with me when I was opening, every one of them stayed with me,” she said.

Chambers even started to see some familiar faces in the parents of the children at her center: former students.

“At the end of the day, it’s about families and community,” she said.

Brittney Selby, Chambers’ daughter, works at the center, greeting parents, teaching, and helping Chambers run the business.

“They have a connection, they talk to her on a personal level,” Selby said of her mother’s relationships with parents. “If they need something, she’s there. If they need help with a light bill, she goes out and beyond to help those parents and make sure their needs are met.”

Since Selby was 9 years old, she has helped her mom and formed connections with children at the center. She now has her associate’s degree from South Piedmont Community College in early childhood education and is a few credits away from completing her bachelor’s degree at UNC-Pembroke.

“This is all I know,” Selby said. “We put so much in and work so hard. For it to go under would be very devastating to me.”

‘Teachers are not knocking on your door’

Chambers began seeing the precursors to current staffing issues a few years before the pandemic. In the last seven years, two teachers retired, two died, and one went on disability. She struggled to find teachers with their level of experience and work ethic.

She raised pay — she offers about $11 an hour to start, and $14 to $15 for teachers with associate degrees and experience. The median wage for a child care teacher in North Carolina in 2019 was $10.62, compared with $12.83 for preschool teachers and $27.89 for kindergarten teachers.

Then the pandemic hit, and Chambers lost four teachers. Her enrollment fell from 51 to 26 children because of a combination of parents’ hesitancy and staffing issues. Most recently, she had to close her infant classroom.

“We can’t take any more children because (we) don’t have the teachers,” she said. “…Teachers are not knocking on your door for the job.”

Across the state, a third of child care providers responding to a September survey said they’ve had to close classrooms with little notice to parents because of staffing shortages. Providers who responded were looking for an average of 4.5 teachers.

Most respondents said they were finding it harder to recruit and retain teachers than before the pandemic, and had lost teachers (2.5 on average) and students (7 on average) since March 2020.

“When I talk with teachers and just ask them in general, why is it that they’re not seeking employment … they say that the work is just too overwhelming for the pay,” she said.

Chambers said she plans to use some of the stabilization funds to give her teachers bonuses but is hesitant to raise base pay without a way to sustain it long-term.

“I’m hoping it is enough to keep us above water,” she said.

‘We just need to get it done’

Past this moment of relief, a combination of federal and state policymaking will influence the decisions of Chambers and thousands like her — and the well-being of children, families, and businesses.

Over the next six years, the federal Build Back Better legislation, passed by the U.S. House last month, would make historic investments in child care and preschool. If it’s passed and signed by President Biden, $400 billion would be earmarked to confront the landscape’s shortcomings, subsidizing the cost of care for the majority of families, establishing universal pre-K for 3- and 4-year-olds, and raising pay for teachers.

North Carolina would receive about $3.34 billion in the next three years in federal funds. But states would have to opt in and provide matching funds to implement the initiatives.

State business leaders held a news conference last month to draw attention to the need for child care funding and workforce support. The group, under the organization ReadyNation, also released a report, titled “Child Care Providers: The Workforce Behind the Workforce in North Carolina.”

This is “a market failure that cries out for policy solutions,” said John Lumpkin, president of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina Foundation. “Now, for our children’s sake, and to protect the future of our nation and our state, we just need to get it done.”

In the meantime, Chambers is hopping on webinars about immunizations and grant funding, starting a COVID testing program for students and parents, and searching for teachers.

She is telling parents, some old and some new, to call back each month to see whether anything has changed. And starting this week, her center is closed for its first 14-day quarantine after a child tested positive for COVID. A large portion of the first round of stabilization funds (she received $24,000 at the end of November) will be used to pay her teachers while the center is closed since she does not want to charge parents — many of whom are now missing work.

“I’m grateful for all that I got because it’s more than I ever have before,” Chambers said this week, but she added that she thought it would be more. “I feel defeated.”

Her daughter Selby is hoping for sustainable change.

“I hope that the funding is there to help kids, to help the teachers,” she said. “I feel like all of us would benefit from it. Our kids don’t need to suffer because we don’t have teachers.”