It was hard to miss the gravity of the equity and whole-child work before our state’s education leaders at last week’s State Board of Education planning and work sessions. Equally evident were reminders of the passage of time with only incremental progress.

Do our leaders believe change requires more than just talking about it? That is the question before both the State Board and the Department of Public Instruction as they implement the Board’s strategic plan and the work continues in schools across the state.

It was nearly three years ago when members of both bodies met in the very room where they gathered last week, tucked behind the front desk of the DPI Education Building in downtown Raleigh. On that day, the room buzzed with excitement as education leaders flitted about the space. They scribbled ideas on poster boards and covered the walls with Post-it notes as they brainstormed objectives and action items for a strategic plan that would set a trio of five-year goals for the state.

Several months later, they gathered in Greensboro at North Carolina A&T State University, and they earnestly asked themselves: When will we see action?

Last week, many of those same Board members gathered again, alongside some new appointees, a new superintendent, and a largely revamped DPI team. There was optimism over the renewed capacity of DPI and Board leadership to govern collectively since the inauguration of State Superintendent Catherine Truitt, but it was balanced by consternation over the lack of progress.

And not just over the past three years.

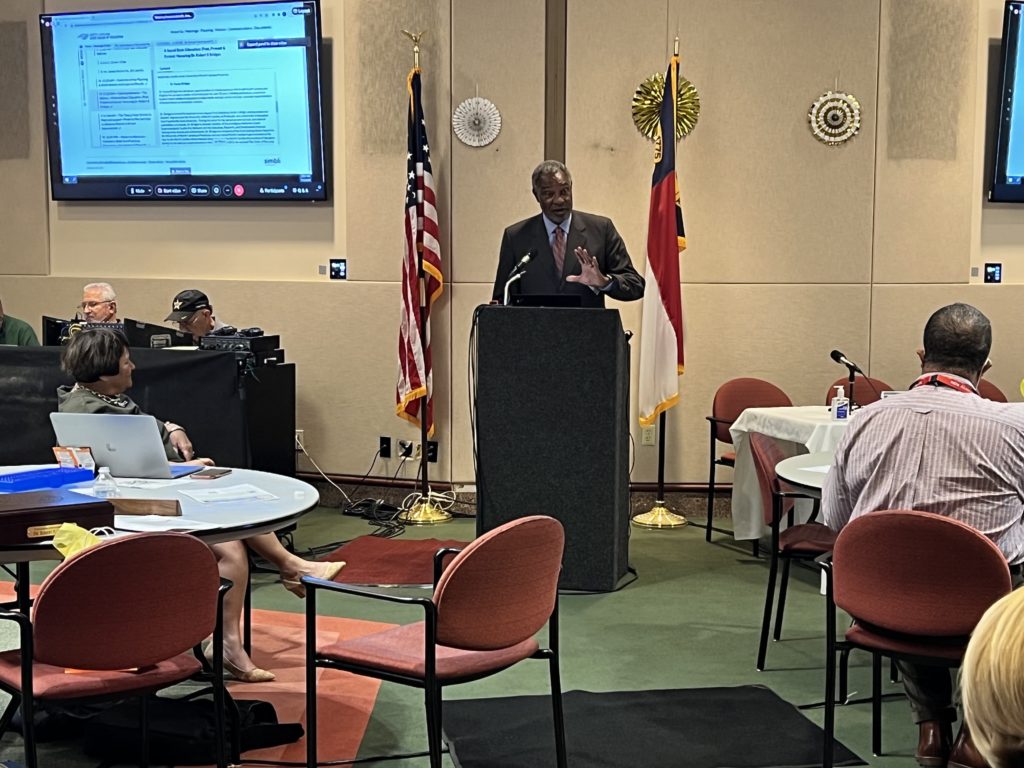

As former superintendent Randy Bridges delivered an opening keynote, the large screens in the room — all five of them — impressed upon their viewers a somber reminder. The televisions froze the cover image of a 2001 report drafted by a team led by Bridges’ father, the late Robert E. Bridges.

That report sought to address many of the issues still plaguing schools today, including issues the State Board considered last week. Twenty years, and still talking about the same stuff.

In fact, many of those issues are identical to those addressed in the Leandro Plan, which emanates from a case filed 27 years ago.

“Twenty years from now, I don’t want to hear the same thing I heard 20 years ago,” said State Board member Reginald Keenan, who was first appointed to the Board in 2009 and began serving on the Duplin County School Board in 1989.

“But some of the things we talked about today, I was dealing with them 20 years ago. … It shouldn’t be that way. The reason it’s that way is because of leadership.”

Impatience gave way to vulnerability when the gravity of the work was laid bare twice, in the span of hours, as two grown men shed tears while thinking about the sort of education the children dearest to them might receive — or, perhaps more accurately, might not receive.

Students benefit from equity-centered schools and SEL

The room filled with hope several times when impassioned presenters reminded State Board members and DPI leaders that there is a way to reach the strategic plan’s objectives through addressing equity with intention and embracing a model of whole child, whole school, whole community.

The strategic plan is, after all, grounded in principles of equity and serving the whole child.

Presenters talked about the importance of bias training for adults to reduce the discipline disparities among racial subgroups. Two presenters spoke at length about the benefits of adopting healing and restorative interventions in place of punitive-focused discipline. A panel of teachers conveyed success through prioritizing social-emotional learning, and leaders from Rockingham County Schools talked about their wrap-around approach to whole-child work.

These presenters acknowledged that adults can disagree about the best way to teach kids but that, ultimately, education is for the benefit of kids. Our kids are human, they said, and humans need to feel belonging. That means they need an adult in their lives who loves them.

And because kids spend most of their waking hours in school buildings, one presenter said, we also need to care for the adults who care for the kids. Another presenter added that adults can punish kids all they want, but measurable change in outcomes will be the result of healing kids instead.

Will Weeks, an educator-turned-resilience-coach in Michigan, spoke to planning and work session attendees about the importance of trauma-informed, resilient schools through social-emotional support.

A panel of North Carolina teachers later shared their experience connecting with students and improving academic outcomes through social-emotional learning, including by establishing belonging and inviting students to share both their feelings and their culture in class.

The current state teacher of the year, Eugenia Floyd, shared how she does this through such restorative practices as healing circles.

Iheoma Iruka, a research professor in the Department of Public Policy and the founding director of the Equity Research Action Coalition at Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute at UNC, urged attendees to uncover racism and systemic inequities in the education system.

![]() Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Don’t sit idly in the problem, she said — a tendency she called gap gazing, where people can get stuck looking at the data and evidence of opportunity gaps among racial subgroups of students. Instead, she called on the Board to take action that centers equity in order to dismantle systemic racism.

“I encourage you all to think about how do you think about school as a healing place,” she said. “It’s a learning place, but it could also be a healing place.”

Why hasn’t the talk led to more action?

The State Board has heard presentations on whole child supports, social-emotional learning, and equity before. Its Whole Child NC Advisory Committee, which provided the Board recommendations in 2019, is about four years old. And just last year, the Board heard from constitutional scholar Ann McColl about the history of racism in North Carolina’s education system and the urgency in addressing its persistent effects now.

So why hasn’t there been more movement toward its goals? The complicated politics of a complicated state creates challenges at the state and local levels.

Politics has bled into education practice nationwide, including in North Carolina, where fear stoked around critical race theory has morphed into restraints and resistance over teaching history as well as social-emotional learning.

The state’s distinctive funding system, as one of only a few jurisdictions where the General Assembly controls education spending, introduces complexity as well – with the judicial branch having ordered higher levels of spending just to meet minimum constitutional requirements without buy-in from the legislative branch.

“It’s my hope that we leave this planning and work session re-energized and inspired to continue to do the work — even through challenge, and sometimes opposition,” State Board Strategic Planning Committee Co-Chair James Ford said.

To not press onward, Iruka said, causes harm to kids.

“We do have to make sure that our [educator] workforce understands the root of systemic inequities,” she said. “You cannot continue to come into classrooms and not realize that. You’re causing harm, whether intentionally or not. … We want to make sure that our youngest people, our children, our citizens are protected at all costs.”

That protection includes making sure they are ready to learn. But not all kids show up to schools OK.

“SEL helps to create learning environments, and opportunities where all individuals can reach their full potential,” said Beth Rice, a regional director for DPI – urging leadership to voice support for SEL in schools.

“We know that your continued communication to your commitment to social and emotional learning as a lever for both academic success and educational equity removes barriers for the field,” she said.

In a vacuum, school districts may find it difficult to adopt or continue programs directed at meeting student needs. For example, multiple sources at DPI confirmed that more than one district declined statewide funding for the Panorama social-emotional dashboard, and two districts even pulled out of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey because of parent and community pressure.

What will DPI and State Board leadership on these issues look like?

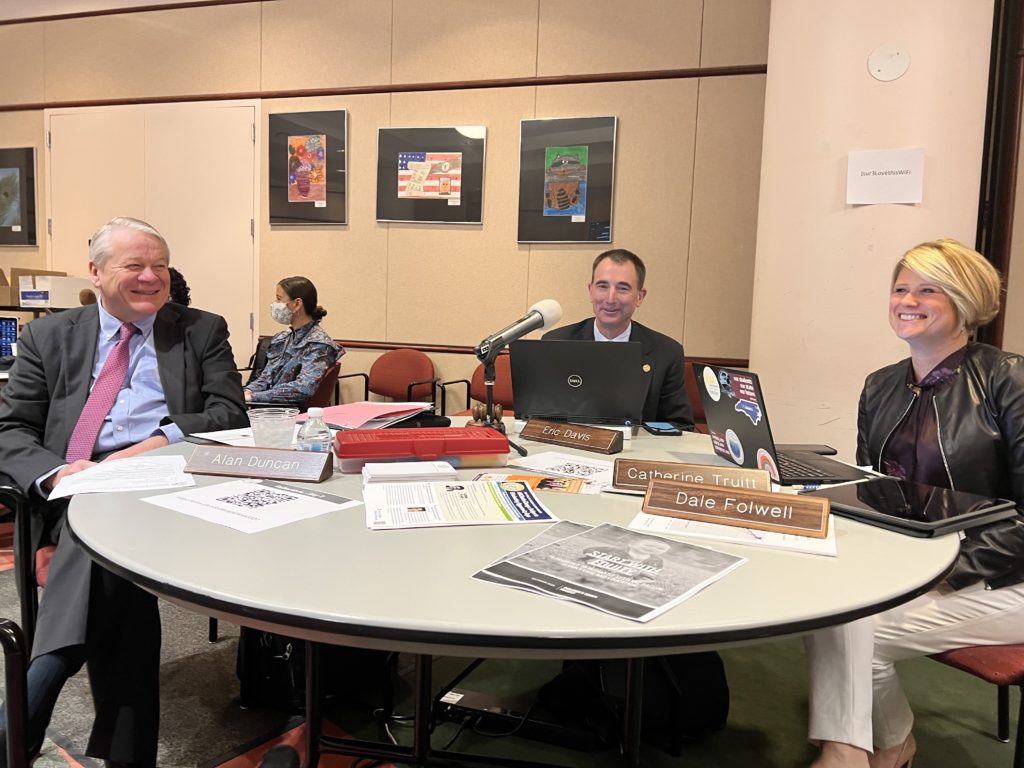

As educators told the State Board and DPI team that they are looking for leadership, State Board Chair Eric Davis offered his commitment.

“Since 2018, we have and will continue to remain steadfast to upholding our guiding principles focused on education equity for all students and educating the whole child,” he said. “And what we’ve learned, especially during the COVID experience, is that these guiding principles are central to providing quality opportunity and access for our students.”

There was some optimism that a more collaborative relationship between the State Board and DPI could help.

Freebird McKinney, director of government affairs and community outreach for both the State Board and DPI, said the conversations and work last week during the planning sessions would not have been possible last year, referencing when former superintendent Mark Johnson led DPI.

McKinney moderated a panel of DPI directors who are working with leadership to draft an implementation guide for the strategic plan, which Davis suggested would be a document both bodies could work on together. Davis asked to see a working draft at the Board meeting in January.

McKinney, who was first hired by Johnson, didn’t mention the former superintendent by name. But he directed his eyes to a table where Truitt, Davis, and State Board Vice Chair Alan Duncan sat together.

“We had a void for a while and we’ve come through that in the last 11 months,” McKinney said. “… It’s absolutely night and day. There’s a fight still in us. We still have a lot to do, but I just wanted to take that time to reflect on that. We have a real opportunity here.”

Recommended reading