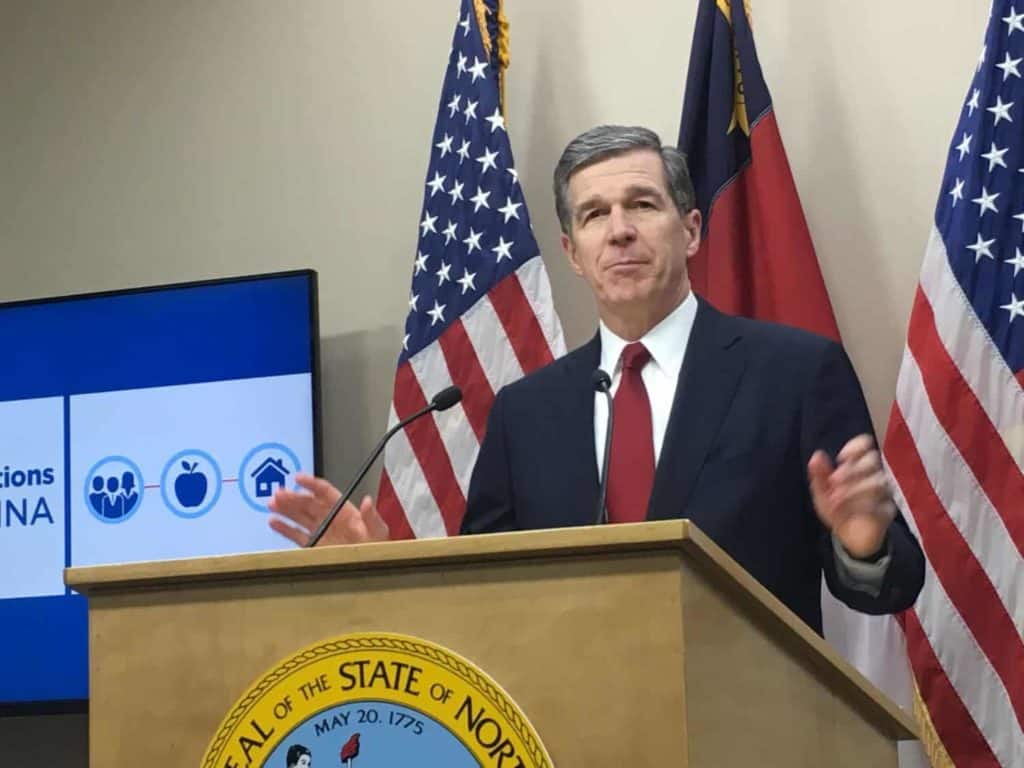

Gov. Roy Cooper told his teacher advisory committee Monday that it is the most important committee he has because it helps him keep his finger on the pulse of educators across the state.

And the message from Cooper and from advisory committee members was that those educators are struggling.

“A number of teachers that I talked to just can’t take it anymore. They just can’t,” Cooper told the committee. “They can’t take the unjustified criticism. They can’t take the lack of salary increases. They can’t take living in a situation with the pandemic in the classroom and the elevated risk that is sometimes there. And so they’re leaving. They’ve just had enough.”

![]() Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

The committee, made up of a variety of educators from across the state, advises Cooper on educational issues. Cooper said the work of the committee is even more important now that he is limited in his ability to go into public schools due to COVID-19.

He told committee members that there is work that needs to be done in education, but that he wasn’t there to tell them about it.

“We hear enough about that from people who are attacking public education and about half of that isn’t even true,” Cooper said.

Instead, Cooper said, while the state is investing more in public schools, it isn’t doing so at a rate that keeps pace with the student population. As a result, school funding is falling behind. Meanwhile, the state is also having trouble attracting and retaining high-quality and diverse teachers.

According to Cooper, his budget laid out a plan for the state to meet its constitutional requirement for a sound basic education, a reference to the long-running Leandro case.

In a matter of weeks, the judge in the Leandro case is preparing to hear from plaintiffs and defendants as to what they think he should do to hold lawmakers accountable for not funding a comprehensive plan that aims to address the educational inadequacies that have been laid out in Supreme Court cases over the educational system in North Carolina.

Cooper’s biennium budget proposal would have fully funded the first two years of that plan — proposals by the House and Senate would fund only a fraction.

The House, Senate, and Cooper are still in budget negotiations, and Cooper asked the committee to give him more time so that he can get a better budget that invests in education and health care.

Bobbie Cavnar, a teacher at South Point High School in Gaston County and a former state teacher of the year, told Cooper that teachers in his district are “drowning.”

“We can’t get enough teachers, bus drivers, janitors. We have no janitors currently in the building, so we all do our own trash and mop our floors,” he said. “Our kids are showing up about 40 minutes late because we don’t have enough bus drivers to get them there on time.”

Cooper said he is hearing similar stories from teachers around the state. He said that North Carolina had a problem maintaining its teacher pipeline even before the pandemic, and COVID-19 has only exacerbated the problem.

“If I could do this budget myself, you all would have a great budget,” he told the committee members.

![]() Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

After Cooper left, committee members had a chance to report out on what is happening in their districts and how educators are coping. Many of the stories lined up with what Cavnar told Cooper.

Keana Triplett, a teacher at Watauga High School in Watauga County and a former state teacher of the year, said that one of the things her district has done to lessen the burden on teachers is to eliminate district-required professional development. She said that in the past, she would have professional development three or four times a month at the high school level, and that the district had never before made professional development optional. But it still isn’t enough, she said.

“I wish I could tell you that that was working, but my door is constantly closed with teachers in tears and ready to quit every day,” she said.

Lisa Godwin, a teacher in Onslow County and a former teacher of the year, said that all of the freedom has been taken out of teaching for her.

She said the curriculum she has for her students is all scripted, requiring things such as 120 minutes of “skills and knowledge” that is dry and not developmentally appropriate. And she said that if a teacher doesn’t do it, they are “dinged” for it.

“It’s breaking my heart, because I’ve been doing this for 24 years and I know what’s good for kids, and I’m not doing what’s good for kids anymore,” she said.

Rodney Pierce, a middle school social studies teacher in Nash County, talked about the impact attacks on so-called “critical race theory” are having on history teachers like himself.

“We have a lieutenant governor who is coming after us saying that we’re trying to indoctrinate children. This is on top of everything else you’re dealing with that’s already been said on the call,” he said.

Elyse McRae, a Pitt County high school teacher, said that at her school, parents call in to ask to see the curriculum of African-American studies classes that their children aren’t even enrolled in, or people ask teachers if they are teaching “critical race theory” without being able to explain what the theory is.

“It is very difficult as a social studies educator to keep people in the classroom when they’re scared,” she said.

Tomika Altman-Lewis, an elementary school teacher in Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools, said that the climate in the state would remain balanced against educators until teachers went en masse to the ballot box to vote as one group.

Dayson Pasión, the new teacher advisor to Cooper and head of the advisory committee, told committee members that they can’t let anything stop them from having the “difficult but necessary” discussions about things like systemic racism and its impact.

“We have a profound responsibility in shaping the future, and it’s more important than ever that we ensure that our students see themselves in the stories we tell, in the histories we learn, in the futures we dream,” Pasión said.

Recommended reading