|

|

Improving children’s reading proficiency has been at the forefront of North Carolina policymakers’ agendas in recent years. A law passed this year will change the way teachers in pre-K through third grade are prepared to teach children to read.

Yet children’s environments before they reach pre-K or kindergarten also play an important role in learning and literacy, said Ginger Young, founder and executive director of Book Harvest, a nonprofit in Durham. A new study of that organization’s literacy-focused home visiting program, Book Babies, has found promising outcomes for parents and children.

“I routinely wake up in the morning thinking about the fact that 90% of the brain is developed in the first five years, and wondering what we’re doing to make the most of that spectacular window of opportunity,” Young said on a webinar last week. The gathering was held to discuss a longitudinal study’s findings — along with a qualitative report on parent focus groups and a survey on families’ experiences with the program.

“And I’m haunted by also the notion that we have failed to tap the most potent and amazing resource right within arm’s reach of these children who are developing so quickly and so spectacularly, which is parents themselves,” Young said.

100 books from birth

The longitudinal study, which started in 2017 and was cut short in March 2020 by the pandemic, found that Book Babies parents in Winston-Salem and Durham were engaged in more literacy practices than control groups. Parents in both locations reported higher rates of ease in their ability to read, how often they read to their children, and how often they pointed at text while doing so.

The study also found children who were assessed in Spanish had stronger early literacy skills than control groups. These skills were reported by parents using tools that capture such skills as vocabulary production and comprehension. Independent researchers were unable to assess children’s skills because of the study’s unexpected end last year.

The first four years of the Book Babies program includes quarterly visits by literacy coaches. The fifth year focuses on the child’s transition into school. Along the way, the coaches give families 100 books and a research-informed curriculum.

“Beginning to center meeting children’s needs before and after they’re born — it’s so critical, not just for school readiness or kindergarten readiness but really for children’s well-being,” said Iheoma Iruka, who led the longitudinal study starting in 2019. At the time, Iruka was the chief research innovation officer at HighScope Educational Research Foundation. She is now a research professor of public policy and the founding director of the Equity Research Action Coalition at Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute at UNC-Chapel Hill.

“It’s not just about children reading,” Iruka said. “It’s also about families feeling like they have the tools to do their best for their child.”

The program has reached 436 families in both locations, including current participants and alumni. The study included 140 families participating in Book Babies in Durham and about 100 families in Winston-Salem. Families’ literacy habits and children’s early literacy skills were compared with those of control groups of similar size in each location — one that received only books without literacy coaching, and one that received only cash.

In Durham, 93% of families in the study reported an annual income of less than $35,000, and 48% reported an income less than $15,000. In Winston-Salem, 87% of families reported an annual income of less than $35,000, and 31% reported less than $15,000.

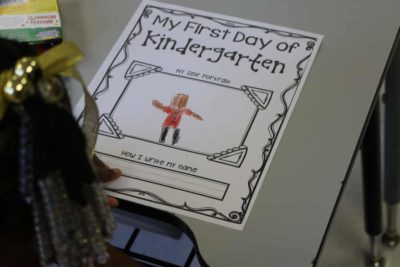

‘The prelude to every single child being kindergarten-ready’

The study looked at children’s early literacy skills of vocabulary production and comprehension at the fourth and fifth visits in Durham and the third and fourth visits in Winton-Salem. The size of the program’s effect was bigger for children assessed in Spanish, with Spanish-speaking children in Durham showing more growth in production and comprehension than the control groups. There was a similar pattern in Winston-Salem.

English-speaking children in Durham showed similar growth to children in the control groups. In Winston-Salem, English-speaking children showed more growth in production than control groups.

Iruka said she does not have a definitive answer as to why the study’s results were stronger for Spanish-speaking children, as the English and Spanish versions of the inventory are not comparable.

“I have been part of other early childhood intervention programming where we have seen a significant growth for Spanish speakers vs. English speakers,” Iruka wrote in an email. “It does speak to the benefit of being bilingual/multilingual. We know this is a benefit that we tend to ignore… I hope there is another opportunity where we can see how the kids are doing (i.e., cognitively, socio-emotionally, physically) as they enter school.”

Young said she would like to see the model be a part of the state’s early childhood “ecosystem.”

“It could be the prelude to every single child being kindergarten-ready,” she said, adding that she’d like to see more programs with longitudinal studies that start at birth.

“I think we have failed as a society to measure what matters, and if we can only measure one thing and make a throughline from that to kindergarten readiness, it would be whether a parent and a child have a reading behavior that is consistent (and) that starts early on. … If I can only influence one piece of that first-five-years ecosystem, it would be to have the parent glimpse their power as the child’s brain builder.”