|

|

The thrust of North Carolina’s new reading law is an investment in teachers, premised on the belief that teacher knowledge will help kids better than any curriculum or program. But there are four separate systems that educate and support teachers in the state, so coordinating efforts will be critical for that investment to pay off.

The leaders at each of the state’s education preparation programs and its education department say that’s what they’re seeing. They say they’ve formed deep relationships with their counterparts across systems and believe teachers ultimately will feel a continuum of support from the time they are aspiring educators in college through the days they’re leading their own classrooms full of kids.

“We have this expectation of the critical things that a teacher of reading needs to know and be able to do,” said Laura Bilbro-Berry, who directs the UNC System educator preparation program (EPP). “They’re going to get that within their ed prep program, and then our K-12 partners are working with in-service teachers to get the science of reading into those classrooms. So we feel like it’s a really good continuum of support.”

Leaders who know — and like — one another

The systems preparing future teachers — the UNC System, North Carolina Independent Colleges and Universities (NCICU), and, with the addition of associate degree programs in teacher preparation, the North Carolina Community College System — represent nearly 100 colleges and universities.

But early implementation efforts don’t look as if every university or school district is on its own. That, in part, is because the system leaders are working together to set up uniform guidance for the effort.

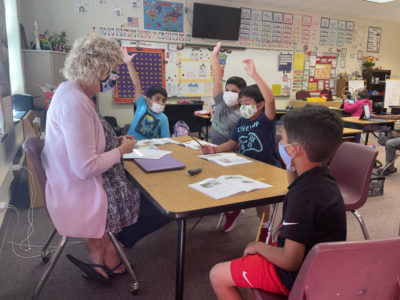

Photo courtesy Laura Bilbro-Berry.

The UNC System is coalescing around a Literacy Framework for each of its 15 educator preparation programs, the NCICU is forming a task force to focus implementation at its 31 colleges of education, and the community college system is working as one unit to design a literacy class that will be required for its new teacher preparation degrees.

“It’s rare in education policy for all the ships to be rowing in the same direction,” UNC System President Peter Hans said. “But it feels as though that is the case. And I can’t think of a more important issue for everyone to be aligned.”

It’s not just leaders within each system working together, it’s also leaders working together across the systems.

“She’s a genius,” Bilbro-Berry says of Monica Campbell, chair of a NCICU college of education. Hans says that Lisa Mabe Eads, of the community college system, hung the moon. The Department of Public Instruction’s (DPI) Amy Rhyne says Bilbro-Berry is “just amazing.”

There’s no shortage of admiration — which has made working together feel natural, they say.

“They’re great relationships, and that’s a good thing because now we’re talking to each other all the time,” said Rhyne, DPI’s director of early learning.

Frequent meetings and conversations

Eads, the associate vice president of academic programs for the community college system, has had several meetings with the UNC System and NCICU. They are working together to design crosswalks that will help community college students transfer to four-year institutions to complete their teacher training.

Bilbro-Berry is on the phone often with Campbell, who established the widely praised literacy program at Lenoir-Rhyne University. She has worked with Eads too, as the two systems are finalizing an articulation agreement that ensures credits will transfer for teacher prep students in community colleges when they move on to UNC System schools. Eads has already worked with NCICU leadership to ink an articulation agreement with those schools.

The teamwork is not just at the educator preparation level. These leaders also meet regularly with DPI leadership. They’re making sure their literacy plans, such as DPI’s Comprehensive Plan for Reading Achievement and the UNC System’s Literacy Framework, are complementary.

The documents share common DNA, drawing from recommendations of a literacy task force the State Board of Education convened in 2020.

Since January, DPI has held monthly meetings of its Operation Polaris Literacy Task Force, an interagency group led by Deputy Superintendent Catherine Edmonds. Bilbro-Berry and Eads serve on the task force, as do Tom West and Phil Kirk. West is vice president for government relations and general counsel of NCICU, and Kirk is its community relations advisor.

“Each individual shares what’s happening in their field,” Rhyne said. “It’s a time for us to learn and ask questions and share.”

It’s not their only opportunity to do that. They frequently pick up the phone or trade feedback in Google Docs.

“That’s almost every other day,” Rhyne said.

Partnering in innovation

Recently, the UNC System received a $2 million grant from the Goodnight Educational Foundation and the C.D. Spangler Foundation that will allow it to pilot partnerships between five of its EPPs and local school districts.

The five EPPs, which the UNC System calls “literacy innovation leaders,” are Appalachian State University, North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, Fayetteville State University, UNC Charlotte, and UNC Pembroke.

The system will partner with these literacy innovation leaders to help redesign curriculum, courses, and field experiences. Faculty and teaching candidates from these EPPs will also take part in the LETRS training that DPI is securing for its school districts. In fact, these five will each be part of cohorts with the districts closest to their campus.

“We really want to study that to see how this partnership is going to be impactful, in terms of making sure that we produce great reading teachers through our ed prep programs,” said Bilbro-Berry, who intends to share what the system learns with its partners at other systems.

A common constituency

Each of the educator preparation systems has its own member schools to serve, but the teamwork on literacy instruction has gone smoothly so far because they all serve two common constituencies.

“This is another important example of collaboration among the three higher education sectors for the benefit of students and teachers in North Carolina,” NCICU President Hope Williams said.

Collaborating is the surest route to success, Hans said. He believes the most direct path to better readers is investing in teachers.

“We expect so much of the teachers,” he said. “There’s so many expectations placed on them, but we’re trying to place the expectations on those of us in roles where we can effect change to support those teachers so they can help those students.”

The state won’t see full implementation of the new reading law for at least three years. There’s a lot to do, from reorganizing the coursework in educator preparation programs to establishing student teaching partnerships to in-service teacher training and adoption of new statewide standards and local curricula.

But the alignment across the systems, these leaders say, offers hope.

“This is my 29th year in public education,” Bilbro-Berry said. “And I’ll say it’s probably the first time where I’ve seen so many people in different groups who are really invested in this critical issue.”