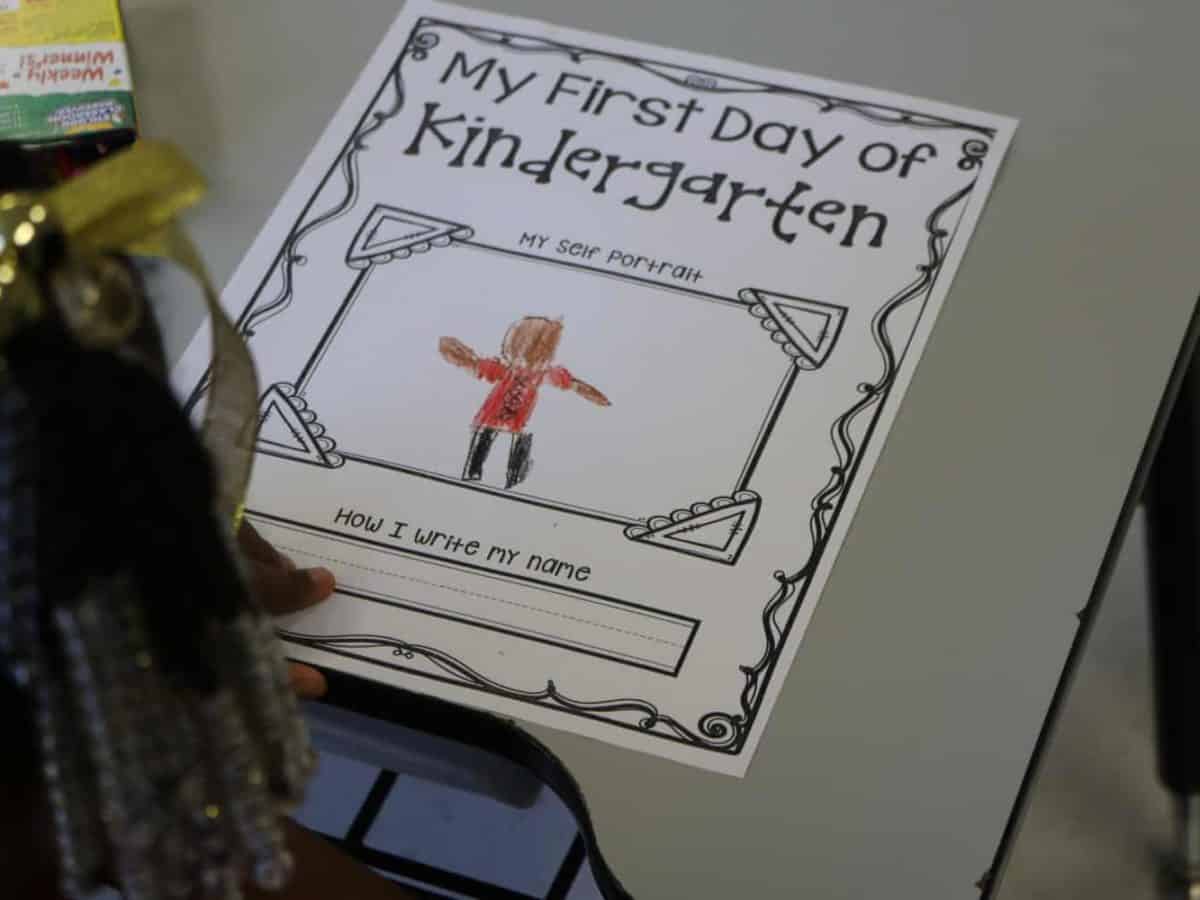

Though every grade looked different last school year in North Carolina, kindergarten classrooms were especially unusual.

And after kindergarten saw the largest decline in average daily membership (ADM) of any K-12 grade last year, what this school year will look like for students and teachers in early grades remains uncertain.

Whether enrollment will bounce back, and how children who missed last year are placed, could lead to larger class sizes, staffing shifts, and classrooms with more diverse sets of student needs.

“We may see an influx,” said Amy Rhyne, director of the Office of Early Learning (OEL) at the Department of Public Instruction, referring to a return by children who did not enroll last year. However, Rhyne said she has not heard of any unexpectedly large kindergarten cohorts so far.

Statewide, kindergarten ADM dropped 15% at the start of the 2020 school year, representing about 16,000 fewer children than the start of the prior year.

The decrease during the pandemic was especially felt in Washington County Schools, where kindergarten ADM dropped 25%. Superintendent Linda Carr said enrollment this year so far has not made up that loss.

“There is still a pervasive hesitation about returning to the building in this county,” Carr said. The district is not offering a virtual academy like some are because it did not make academic or financial sense, she said.

Where children who missed kindergarten end up depends on many local factors, Rhyne said. Ultimately, the principal of the school decides.

“It really depends on the child, the school, the district, how many numbers they’re allocated per teacher … per grade level,” Rhyne said.

![]() Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

Principals in Washington County decide based on age and conversations with the child and then use assessment results to adjust if needed, Carr said. It’s more likely for principals to place children in kindergarten and then move them up if they test higher, she said.

Carr said she has her eye on Senate Bill 654, which would delay requirements for smaller kindergarten class sizes for the upcoming school year. The bill, which is in a conference committee, would allow districts with at least 5% higher kindergarten ADM than they had in the 2019-20 school year to have an average class size of one teacher to 20 students. No single kindergarten class could exceed one teacher to 23 students.

Classrooms might also have students with a more varied set of skills and developmental levels since children were in such a range of environments — some virtual, some in-person, some at home, some in pre-K, some home-schooled. NC Pre-K, the state’s public preschool for at-risk 4-year-olds, went from serving about 25% of the state’s 4-year-olds, or 31,000 children, to about 18%, or 22,000 children.

A research brief from NWEA released in March offers advice for educators and leaders preparing for a more diverse class.

“Because the academic and nonacademic skills students develop in their preschool and early elementary school years are foundational to important longer-term outcomes, understanding

these changes and finding ways to effectively support our youngest students’ learning is critical for educators and leaders,” the research brief begins.

The report recommends the following:

- Expect greater age differences in kindergarten (and some first-grade) classrooms

- Prepare for wider skill disparities upon entry

- Use summer to get kids kindergarten-ready

- Use data to drive evidence-based decision making and understand long-term implications

Teachers in North Carolina use a tool called the NC Early Learning Inventory (NC ELI) to assess incoming kindergartners. Teachers will then need to adjust instruction based on the assessments, Rhyne said.

“Just because a child is in first grade doesn’t mean you start with first-grade standards,” she said. “If they never had the standards in kindergarten, they’re going to have to back up.”

Changes in the NC ELI mean teachers will be required to observe and record more social and emotional aspects of children’s development, said Dan Tetreault, OEL and Read to Achieve project coordinator.

“I think that’ll be helpful in supporting children given the trauma that could exist because of the pandemic,” Tetreault said.

The word “trauma” also came to mind when Carr was planning the start of this school year.

“Our brains are in that fight-or-flight mode,” Carr said. “We’ve got to come back to having people feel comfortable in a trusting and caring environment.”

Before fully diving into academic content, teachers across grades in Washington County will take the first couple of weeks of school to “go back to the basics,” Carr said. That means setting classroom expectations, asking how children are, and building trusting relationships.

“We’re going to have to learn how to do school again,” Carr said. “It’s like we’re all starting over.”

Recommended reading