|

|

Jackie Harris, principal of Granville Early College High School, has accumulated more student mobile phone numbers in the past year than ever before.

“I get calls all times of the day and all times of the night,” Harris said.

Russell Vernon, principal of Rockingham Early College High School, put an alert on his email so that if students didn’t respond within a day, he knew to send them follow-up personal emails.

Maria Ford, principal of Cumberland International Early College High School, jumped between virtual classrooms throughout school days, making sure students turned on their cameras to engage.

This kind of individualized support is a longstanding theme in early colleges across North Carolina. But it was particularly beneficial during pandemic disruptions, said principals at the virtual Early College Summit, a forum organized recently by RTI International to share lessons, encourage educators and leaders, and ask what’s next for early colleges.

“I just think that it’s been a tough year for all of us, and I think having the small early college setting, and being able to interact with our students, interact with our staff, (and) provide that support has made it much easier,” Ford said.

The early college model, which falls under Cooperative Innovative High Schools (CIHS) in state law, allows students to take high school and college courses at the same time, earning associate degrees, workforce credentials, or transferable credits upon graduation. Most early college high schools sit on community college campuses, have smaller populations than traditional high schools, and target specific groups — students at risk of dropping out, first-generation college students, and students who could benefit from accelerated instruction. Some focus on particular subject areas or career paths.

“I think we’re at an inflection point now with early colleges in North Carolina,” said Isaac Lake, a consultant for the Department of Public Instruction’s Division of Advanced Learning and Gifted Education. “I’m sensing that we need to reconnect with who we serve, why, and how, and lift up what’s really working, and then continue to tell our stories — both individually where we are and collectively across the state and across the country.”

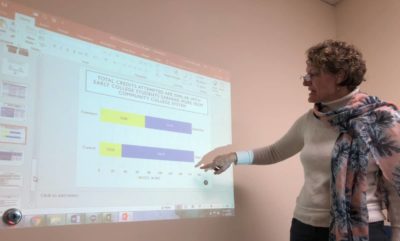

Principals shared points of academic success during the pandemic that they saw as results of that personalized support: a class of seniors with GPAs no lower than 2.7 in Granville, and increases in English II scores from the previous year in Rockingham. Students’ GPAs increased in credit-level spring semester courses from 2019 to 2020, and course success rates declined only slightly, according to an annual CIHS report to the legislature.

CIHS programs historically have performed higher academically, on average, than traditional high schools in North Carolina. Research from UNC-Greensboro’s SERVE Center shows early college students are more likely than their peers in traditional schools to attend class, avoid suspension, graduate high school, enroll in a postsecondary institution, and attain associate degrees. Economically disadvantaged early college students are more likely to attain bachelor’s degrees.

But summit speakers encouraged early college educators to think outside their schools and students, to share their experiences with the education community, and to think about the role of the model in improving outcomes for all students.

“I think the early college is really this test case,” said Julie Edmunds, program director for secondary school reform at the SERVE Center. Edmunds and her team have studied the model since the early 2000s, comparing a cohort of early college students with a cohort of students who were accepted into early colleges but did not attend one through a random lottery.

Along with the significant difference in high school success and degree completion, the team has more recently found that early college students took more advanced courses in college, were less likely to switch majors, and graduated with less debt.

‘A larger responsibility’

Edmunds was part of a summit panel that explored whether and how the model’s successes could be expanded to ensure that more students gain the postsecondary attainment needed for most jobs in today’s economy.

“I think we might all have a larger responsibility to thinking about how we can re-envision the education system so that it can work for more students,” she said.

Presenting alongside Edmunds were Nina Arshavsky, a senior research specialist at the SERVE Center, and Beth Glennie, a senior research analyst at RTI International.

Less than half of 25- to 44-year-olds in North Carolina, 1.3 million people, have some degree or credential beyond high school, according to myFutureNC, a cross-sector group with a goal to increase that number to 2 million by 2030. Between 1980 and 2015, jobs requiring advanced credentials increased by 68%, according to Pew Research Center.

Though enrollment in postsecondary institutions has increased in recent years, Glennie said, racial disparities persist. In 2020, 62.7% of the year’s high school graduates from 16 to 24 years old were enrolled in college by October, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Breaking that percentage down by race, 83.2% of Asian students and 62.9% of white students enrolled, while 56.6% of Black graduates and 56.2% of Hispanic graduates did.

“Getting there is only half the battle,” Glennie said. Research has found that 40% to 60% of U.S. college students take remedial courses to catch up in basic subjects before working toward their degrees, which increases the cost of attainment. These data also show disparities by income and race.

“Why would there be this need for remedial course taking and some groups not enrolling and succeeding in college?” Glennie asked. “There are several different kinds of gaps between high school and college, and these have resulted from a disconnect historically between high school and college. They were created and evolved as separate systems.”

Combining high school and college

Beyond the obvious financial barrier for students, which the early college model reduces, Glennie shared other types of obstacles to postsecondary attainment: logistical, cultural, and academic. By combining high school and college, the early college model helps students be prepared for college-level academic rigor, provides guidance for students through the transition from high school to college, and helps students feel more comfortable and confident in postsecondary environments, she said.

The team makes this case in a working paper: “What happens when you combine high school and college? The impact of the early college model on postsecondary performance and completion.”

“So the question is: What can we do to actually expand this model for more students?” Arshavsky said. Some states, like North Carolina, have increased the number of standalone early colleges on college campuses. In 2020-21, there were 132 CIHS programs across the state. Texas is the only state with more.

In some states, early college academies are on high school campuses or in a central location in a district, operating similarly through an elective process where students choose to apply.

The third expansion model, Arshavsky said, is to create early colleges within comprehensive high schools, where all students are eligible, but not required, to take courses.

Participants chimed in with potential challenges in early college expansion, such as teacher buy-in, space, teacher capacity at the high school and college levels, and financial limits.

Arshavsky then outlined policy supports that could help states navigate these challenges: clear definitions of early colleges and a process to authorize them; financial commitments from multiple institutions; more opportunities for students to take college-level courses in high school and to transfer them between institutions; and intermediary organizations that support early college networks.

Important design principles to scale up early colleges, she said, include strong postsecondary partnerships with clearly articulated agreements, curriculum requirements and pathways, and college readiness supports for students.

‘The road is long and challenging’

In an Early College Expansion Partnership, the team tested what it would mean to turn comprehensive schools into early colleges in Texas and Colorado. The project’s evaluation found needed changes for the schools included “creating a more college-going culture, implementing college readiness activities, modifying instruction to be more rigorous and student-centered, providing student supports, and fostering increased learning and collaboration for school staff.”

“Results from this evaluation suggest that comprehensive high schools can begin the process of transforming themselves into Early Colleges but that the road is long and challenging,” the report says.

The study found increasing access to college courses, which many traditional schools already have through dual enrollment, is only the start. The researchers argued that early college “is not just ‘dual enrollment on steroids,'” but is based on these ideas:

- “All students, not just a subset, should be expected to prepare for some sort of postsecondary education (two-year or four-year or technical credentials).

- All students should have the opportunity to attain some sort of a postsecondary credential as part of their high school experience.

- College courses should not be just an add-on to the school, rather, the focus on postsecondary readiness requires schools to reconsider how all aspects of the school (e.g., instruction, supports, high school coursetaking, the professional working environment) can support the common goal of postsecondary readiness for all.”

The extent to which early college expansion can take place will depend on current leaders sharing best practices, Edmunds said as she called on summit participants.

“You have this huge role and this huge responsibility and these huge opportunities to really make a tremendous difference in the education system right now,” she said. “We’d encourage you to think about ways of doing that and ways of working with the other schools in your community to make that happen.”