North Carolina ranked 26 in preschool access in the country in the 2019-20 school year, according to a new report, while barriers to program expansion left about half of eligible children unserved.

Reaching more children with high-quality pre-K will require addressing those barriers with increased funding, said Steven Barnett, senior co-director of the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) at Rutgers University and co-author of the 2020 State of Preschool Yearbook.

“Limitations on funding present problems for expansion, because essentially the low-cost opportunities have been used up in North Carolina, and moving forward is going to be more expensive,” Barnett said on a press call last week.

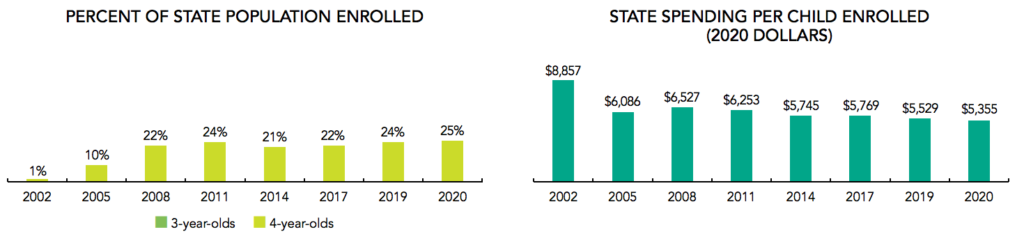

NC Pre-K, the state’s program for at-risk 4-year-olds, enrolled 25% of 4-year-olds in the 2019-20 school year and no 3-year-olds. The program has reached around a quarter of 4-year-olds, or about half of eligible children, since 2008.

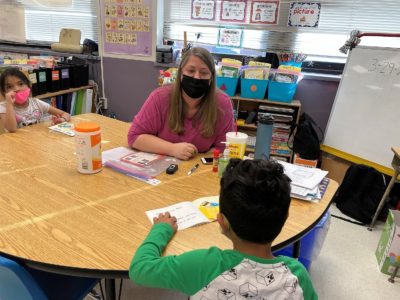

The pandemic has since presented new challenges for preschool access and quality, the report says. Susan Perry, chief deputy secretary of the state Department of Health and Human Services, said 2020-21 NC Pre-K enrollment dropped from around 31,000 to 22,000 children — or 18% of 4-year-olds. More than half of those children, Perry said, were learning remotely.

About half of the state’s 4-year-olds are eligible for the program, which is determined by family income level, as well as other factors like limited English proficiency and special needs. The percentage of eligible children being served varies widely from county to county. In 2017, 23 counties served more than 75% of eligible children, 37 served 50-75%, 37 served 25-50%, and three counties served less than 25%.

The state spent slightly less per child ($5,355) in 2019-20 than in the previous school year ($5,529). Total pre-K spending in North Carolina, which takes into account federal, state, and local funding sources, was $10,122 per child. The state was one of four states and D.C. in which that figure is enough, the report says, to meet NIEER’s quality benchmarks and pay preschool teachers at a level comparable to K-12 teachers.

“That does not mean it is enough money for programs in states that require more than the minimum,” Barnett wrote in an email. “For example, North Carolina has a smaller class size and child:staff ratio making the program more expensive than the minimum. In addition, the total current spending per child we look at is what is reported for those who currently operate — this includes funds from all sources local, state, and federal. Those funds are limited and not everyone has access to them and they do not necessarily cover every eligible child.”

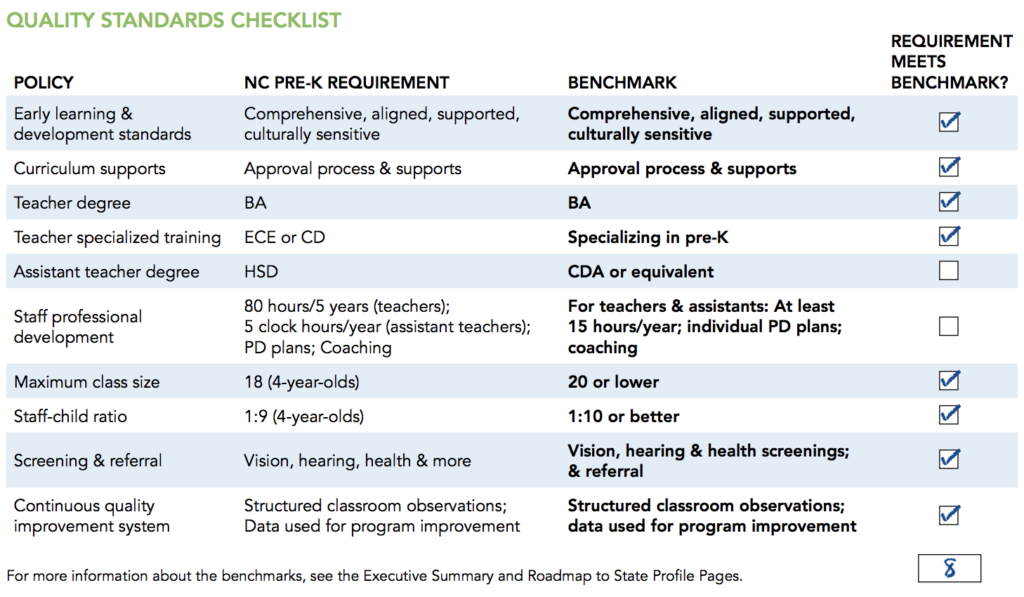

There is not a statewide requirement to pay NC Pre-K teachers with the same education in public and private settings at the same level, though some local communities have done so on their own. The program met eight out of NIEER’s 10 quality benchmarks in 2020.

North Carolina is one of 13 states that requires pre-K providers to match state funds with other sources of funding. The state’s allocation covers about 60% of the cost, and providers (at private child care centers and public schools) use a variety of different funding sources to make up for the other 40% — Head Start, Title 1, local investments, Smart Start, private tuition, and child care subsidy, to name a few.

A 2018 NIEER report specifically studied NC Pre-K and found this combination of resources is not sufficient to reach more eligible children. “Exacerbating that fundamental barrier,” that report found, was a stagnant per-child slot rate and rising operating costs to recruit and retain qualified teachers, provide transportation, and expand facilities.

A 2020 study by the Frank Porter Graham Institute found similar issues: not enough space and not enough funding to cover the full cost of operation.

Multiple bills this legislative session, the remedial Leandro plan, recommendations from a group of business leaders, and Gov. Cooper’s budget aim to expand pre-K access and modify its funding structure.

The NIERR report suggests a cost-sharing plan, detailed here, between federal and state governments to reach universal pre-K for 3 and 4-year-olds, a priority for President Biden. An additional $62 billion is needed nationwide to reach the five million children who are currently unserved, and another $12 billion is needed to increase quality in current state-funded preschool programs.

In North Carolina, the report estimates the federal government would need to spend $218,718,585 over four years to reach universal preschool in the organization’s proposed plan. The report estimates there is currently an 86,228 seat-gap for low-income 3- and 4-year-olds in North Carolina, which would cost $874,955,516. When looking at all unserved 3- and 4-year-olds, the report says there is a 176,395 seat gap with a price tag of $1,789,877,106.

“With each year we delay, a new group of children miss out on critical years of education they will never get back. Preschool was underfunded before the COVID-19 pandemic, which has exacerbated the problem in three significant ways: 1) many states are struggling to maintain even current low levels of funding; 2) many more children missed out on early care and education experiences while programs were closed during the pandemic; and 3) many more families are now experiencing financial hardship. We saw long lasting negative impacts of the 2009 Great Recession on public preschool funding — impacts from which 25 state-funded preschool programs have yet to fully recover. States will be more likely to increase access to high-quality pre-K if they have a partner in the federal government. Past federal efforts to support preschool were highly successful. New federal efforts can reduce policy conflicts across child care, Head Start, and the public schools while offering financial incentives for states to prioritize quality and access to high-quality preschool programs for many millions of preschoolers who could receive a better education each year.”