At times, it’s a helpless feeling. That’s how Samantha Osteen, a third-grade teacher at Brevard Elementary, describes it.

She’s looking at state reading standards and knows that a large part of her job is to help students build fluency and comprehension skills. It’s to help them glean meaning from the words they read.

Each year, though, she realizes that far too many can’t even read words.

“When they come to me, we need to be examining text, and comparing and contrasting, and finding the cause and effect, and all that,” she said. “If they can’t even decode a word, that’s a lot to put on a third-grade teacher.”

It’s not a problem unique to Transylvania County Schools. It’s a challenge statewide, as well as across the country.

In Transylvania, the district started training its elementary teachers in the science of reading in December. Since then, Osteen says, she feels more hopeful.

“It’s a relief for me to hear this and see this,” she said. “This is exactly what my kids need. I don’t have to guess. I can see, this is what they need if I need them to learn how to read, point blank. It’s not impossible. It’s manageable.”

TCS plans more training. Already, teachers completed a one-day training with the North Carolina Center for the Advancement of Teaching, and some received another four-day training through The Reading League. Plans to start training in Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS) are on hold, as the district waits to see what happens with proposed legislation that could impact future district-level training.

Still, already there are changes showing up in the classrooms.

TCS has used Open Court, a phonics curriculum, in its classrooms for five years. What’s changing is how they use it, what teachers are adding to it, and how they run the small groups where they reinforce lessons.

For example, they now start the day doing exercises using Heggerty, a phonemic awareness program they recently started using.

Phonemes are the smallest units of sound in a word, and building awareness and proficiency with these phonemes leads to orthographic mapping, where kids gain automatic recognition of words.

Jennifer Worley, a 20-plus-year veteran who teaches first grade at Rosman Elementary, called the addition of Heggerty “one of the best things I’ve done. I’ve seen so much improvement.”

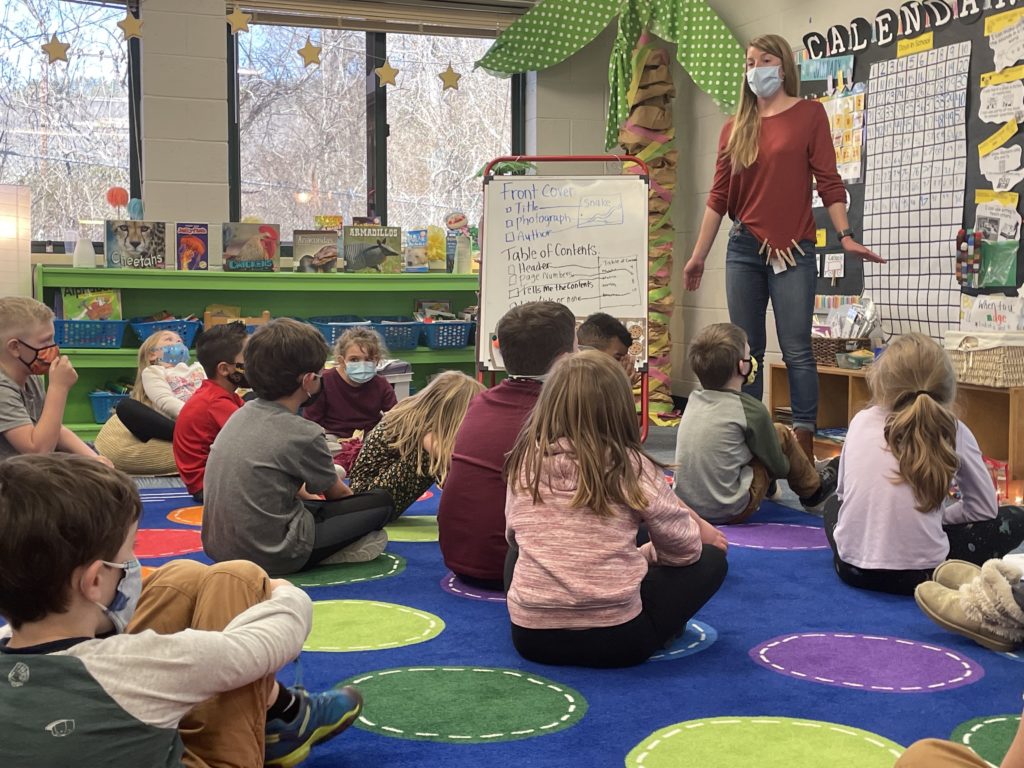

Here’s what it looks like in her classroom:

After starting with phonemic warmups, most classrooms move to Open Court phonics lessons. Teachers say they are becoming more intentional with how to use the curriculum. They’re getting better at using it to create a continuous flow of sounds and words throughout the day.

Students break into small groups next, as they always have. But what happens in those small groups is perhaps the biggest change for many teachers in the district.

Before the training, this was when teachers would guide students through books, prompting them to predict or guess words based on pictures and other contextual clues. That’s a practice tied to the “whole language” approach to reading instruction.

Then students would read on their own, choosing a book that matches the level they were given by their last reading assessment. These books are called leveled readers. Critics say these books encourage guessing at words and also limit student’s ability to learn new words.

“At the start of school, I was definitely getting leveled readers,” said Haley Dawson, a first-grade teacher at Rosman. “Now, I’m like, I’ll ignore that. We’re not doing the cueing system or leveled readers anymore.”

Now, she chooses decodable books that match the phonics lesson students had that morning. She sets the decodables aside for a moment and has students use a sheet of paper with three or four boxes on it. These are called elkonin boxes.

“And I’ll take words from the decodable book that they’re going to see, and that’s what I use in the elkonin boxes,” she said. “We go on a hunt for that sound that we learned earlier; then we highlight it. And then they read it two times, and I come around and listen. And then we talk about it.”

That’s when she gives them the books, and the kids are off reading with their peers or independently.

“I think the switch to a decodable when you’re teaching phonics, rather than taking them in a leveled reading group with a leveled text, is one of the most powerful things,” Osteen said. “Because they’re able to truly use their brain to decode patterns that they have learned.”

Osteen also breaks her class into small groups for what she calls “strategy group” time.

“The strategy group is my number one thing that’s changed, using the lesson plan [grounded in] that science of reading,” she said. “It breaks it down for you, and there’s no guessing. I feel like a lot of times in teaching, it’s like reading is supposed to be smoke and mirrors, and magic, and, you know, no one really knows the answer.”

The answer she’s working toward now includes warming up with phonemes, building words for students and asking them to read words she chooses systematically. Then she has her students build words from sounds she makes. The last thing she does before giving them time to read decodable books is dictate sentences that the students write out.

That’s just one example of a day, she says. But days don’t all look the same.

“It’s not necessarily like, here is a formula for what you have to do day 1, day 2, day 3,” she said. “It’s more like, if-then. Like, if a kid is doing this, then I can do this.”

She marvelled recently at one girl who couldn’t read when she entered Osteen’s classroom. This student has made strides, Osteen said, in just the few weeks since Osteen started her strategy groups.

The child is identifying word parts and reading words. She’s tackling decodable texts and writing.

“And not just her; it has been phenomenal for all the kids that I have in my class this year,” she said. “Some were already behind for many reasons, but also, then there’s the pandemic. But they have made gains already just from doing it the weeks that we have since I learned about that lesson plan.”

It’s a welcome celebration, she says, given the helplessness she once felt.

“Every year,” she says, “there’s always a group of at least three to four kids in third grade that struggle with even decoding words, but then there’s a whole separate group of maybe another three or four kids that have no fluency, and that’s another battle.”

She still thinks about the kids who she couldn’t help in that battle. Her speech slows and softens.

“But that was because I didn’t know,” Osteen said. “We didn’t have the training that I’m getting now. So you have that guilt and that coulda, woulda, shoulda, but I just did not have the knowledge that I have now.”