One piece of big education news this week is the passage of legislation that would require all traditional public schools to bring students back to the classroom in some form or fashion. After a relatively minor disagreement last week, the House and Senate hashed out their differences and both voted on a compromise bill this week.

The main tenets of the bill remain:

The legislation would make schools open for exceptional needs students under plan A, and under either plan A or plan B for all other students. Plan A is full-time in-person education with minimal social distancing. Plan B is typically a hybrid of in-person and remote learning, with six feet of social distancing.

No district would be able to solely offer remote learning to students, but families who want their students to remain fully virtual would still have that option. The bill doesn’t apply to charter schools, only traditional public schools.

In a statement following its passage, Gov. Roy Cooper agreed that students should be back in school but expressed reservations about the bill.

“Children should be back in the classroom safely and I can sign this legislation if it adheres to DHHS health safety guidance for schools and protects the ability of state and local leaders to respond to emergencies,” he said. “This bill currently falls short on both of these fronts.”

Cooper reiterated those points during a COVID-19 press conference Feb. 18. He said that 91 of the 115 school districts in the state have returned to in-person learning, and that 95% of school districts would be doing so by mid-March. He said this was happening, in part, because he and education leaders urged school districts to bring students back a few weeks ago. Cooper also announced last week that teachers could start getting vaccines on Feb. 24.

During the press conference, Cooper also clarified his reasons for not liking the legislation. Specifically, he said he took issue with the fact that the legislation would allow middle and high schoolers back into school with little or no social distancing (plan A). This is the same critique that some Democratic lawmakers had of the bill. They argued that there is limited data in North Carolina on the spread of COVID-19 in these grades under plan A.

That’s because the governor hasn’t allowed any middle or high school to operate under plan A — full-time in-person with little or no distancing — since before the pandemic.

Proponents of the bill, including state Superintendent Catherine Truitt, say that the legislation is necessary and follows Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) guidance. Truitt was one of those education leaders who stood with Cooper earlier this month and urged schools to return students to classrooms. Here is what Truitt said in an emailed statement on the legislation.

“I’ve maintained for the last 10 months that the decision to re-open schools should remain a local one. We know that students need to be back in school for face-to-face instruction, and the science shows us that schools can safely re-open if they adhere to COVID-19 prevention policies.

“I commend the General Assembly for this bipartisan effort, as SB 37 provides local discretion for school districts while allowing our students to be back in the classroom for in-person instruction. This bill is in line DHHS health and safety guidance, requiring school districts to meet all stipulations as set forth in the StrongSchoolsNC Public Health Toolkit. Parents still have a choice in which learning environment is best for their child, while teachers and staff who are uncomfortable returning have alternative options to minimize face-to-face contact and risk of exposure. This is a win for students, parents and districts across the state.”

Now that the bill has passed the General Assembly, the big question is what Cooper will do with it. His statement leaves room for the possibility that he could let the legislation become law after 10 days without signing it, rather than vetoing it. His comments during the press conference on Feb. 18 didn’t clarify matters. He said he will continue to discuss new school reopening legislation with legislative Republicans before doing anything with the bill they’ve already passed.

In a press release on Feb. 18, Sen. Deanna Ballard, R- Watauga, urged him to make a decision now.

“Parents and children have waited long enough for some level of certainty in their public education. I hope that Gov. Cooper chooses not to drag this out for another week and a half,” she said in the release. “This is a two-page bill that’s been in the public for weeks. If a veto is coming, then do it now so the legislature can vote to override.”

Of course, to override the veto would require some Democrats to side with Republicans. And while some did vote for the bill, Democratic lawmakers generally go along with the governor’s vetoes.

Summer learning

A bill that would require each school district in the state to offer a six-week summer program to K-12 students got its first hearing in a House education committee this week.

The legislation focuses on at-risk students and the program would be voluntary for students. For more detail on the particulars, go here.

The bill is the rare piece of legislation with House Speaker Tim Moore, R-Cleveland, as a primary sponsor. The hearing in the House committee this week was for discussion only. The committee will take it up next week for amendments and a vote. The rationale for waiting to vote, according to Rep. John Torbett, R-Gaston, a chair of the committee and co-sponsor of the legislation, is that lawmakers want to make sure they get plenty of input on the bill.

Some of that input is already coming in. If you go to this article from earlier in the week, you will see input that the North Carolina Association of School Administrators is getting from school leaders.

Additionally, during the committee, Democrats like Rep. Graig Meyer, D-Orange, offered some critiques of their own. Meyer said that while he agrees with the legislation in theory, he would like to see more flexibility granted to local districts. He said he has worked in secondary schools, and summer programs are often split up into two, three-week sessions for a maximum of four hours a day to accommodate the fact that some students need to work to help support their families. In addition to being six weeks, the program proposed in the legislation requires five hours of instruction a day.

While there is no money specifically allocated to pay for the program in the legislation, Moore pointed to $1.6 billion in federal COVID-19 aid that is going directly to districts as one way that they could pay for it. They could also use other funding sources, such as allotments for at-risk students or Read to Achieve money, according to Rep. Jeffrey Elmore, R-Wilkes, a co-sponsor of the legislation.

Moore referenced discussions with unnamed district superintendents who he said indicated there is plenty of money to pay for the program.

Greene County Schools Superintendent Patrick Miller, president of the NC School Superintendents Association, had a number of concerns he expressed in a phone interview, though he agreed that there is money to pay for the program.

He said that prior to the legislation, his district was planning to do a six- or seven-week summer program that would run Tuesday through Thursday each week.

“We felt like by doing that, we would have a better shot at getting the number of teachers we need and still allowing them the time they need to rejuvenate and get ready for the next school year,” he said.

He said the fact that the six weeks of the summer program in the bill don’t count toward retirement is going to make it less attractive for teachers, who he said are already exhausted from having to make the hybrid model of instruction in Greene County work.

“I think the kids will come. I think that won’t be an issue. But … I am concerned about having the number of teachers that we need to run an effective program,” Miller said.

Ultimately, he said the district will do whatever the legislature decides, but he said he would like superintendents to have some voice in the the creation of the legislation.

He also advocated for more flexibility in the bill.

“One size clearly does not fit all,” Miller said.

Shelby Armentrout, chief of staff for Truitt, spoke at the education committee and expressed Truitt’s support for the legislation. She pointed out, in particular, a change lawmakers have already made to the bill. Instead of saying six weeks, it now says the summer program should be 150 hours. Armentrout said she thinks that will give districts more of the flexibility they are looking for.

Meisha Evans, a policy attorney with Disability Rights North Carolina, also spoke at the committee and praised the legislation and its potential impact for students with disabilities.

“While remote instruction has played an important role in making schools safer … there are students with disabilities who don’t have access to remote instruction,” Evans said.

During his COVID-19 press conference on Feb. 18, Cooper was asked about the summer learning legislation. He said he approves of programs that will help students catch up and that he looks forward to giving input on the legislation as lawmakers get feedback from people around the state.

How much money do we have?

Lawmakers heard presentations that outlined roughly how much money the state is going to have available when it budgets for the next two years.

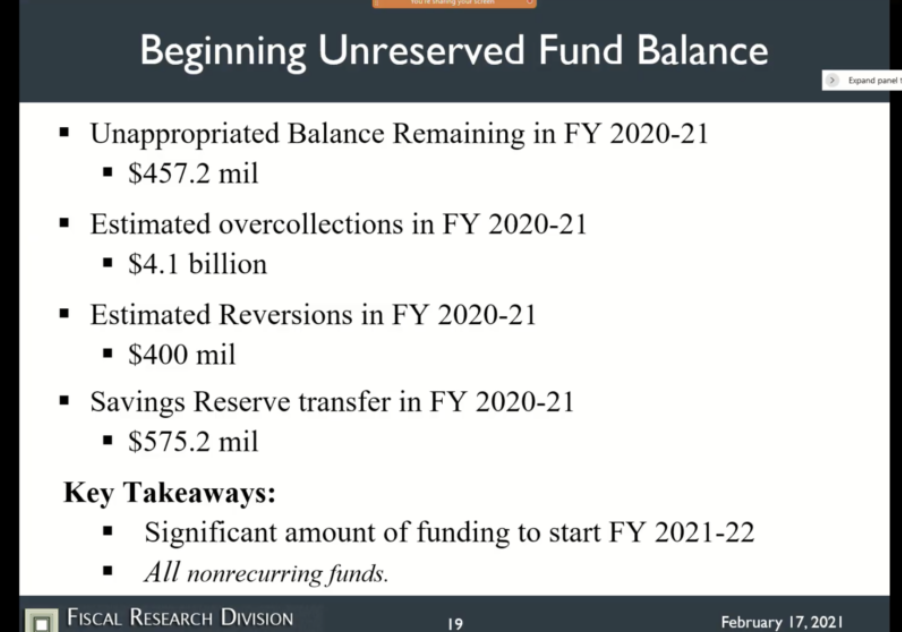

A consensus revenue forecast recently revealed that revenues for fiscal year 2020-21 will exceed expectations by about $4.1 billion.

In a presentation to lawmakers on budget availability Wednesday, legislative staff also laid out all the other pots of money that the state is starting with going into the budget planning session. You can see those funds in the slide below, but note that all of this money is non-recurring. It can be used one time, and then it’s gone.

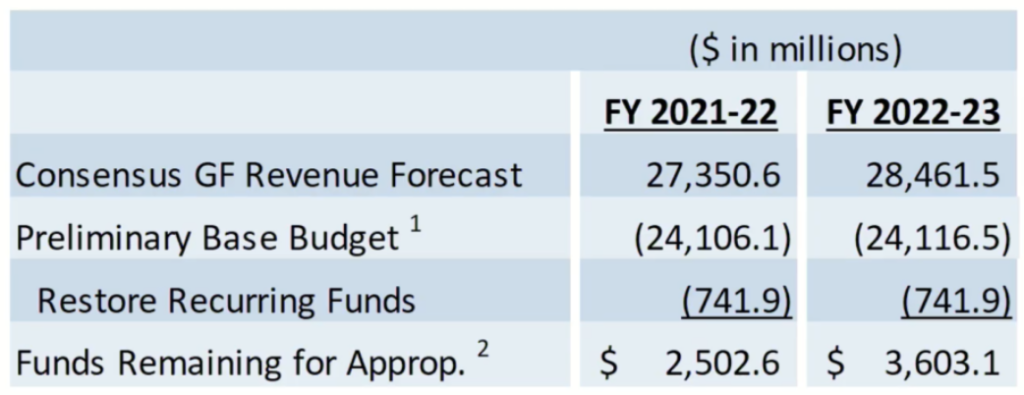

Lawmakers also got a look at how much money they have to work with on a recurring basis. You can see in the chart below that in the first year, there is expected to be about $2.5 billion, and in the second year, about $3.6 billion.

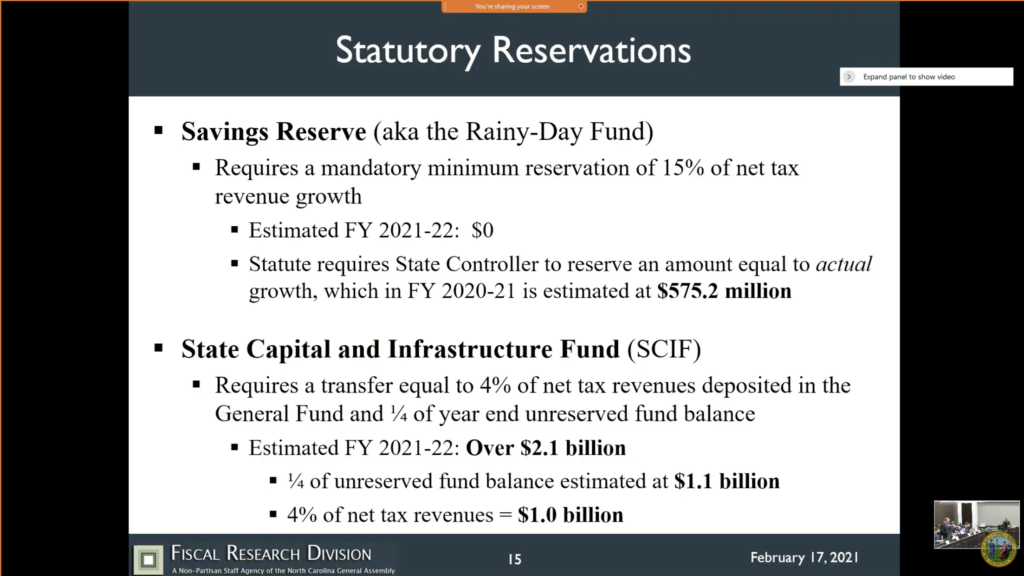

There are caveats to that, however. There are some statutory requirements that need to be fulfilled. Specifically, some money needs to go into the rainy-day fund and the State Capital and Infrastructure Fund (SCIF). For the first year, only $1 billion will be siphoned away, and that will go into the SCIF. That leaves lawmakers with about $1.5 billion recurring. It’s too soon to tell how much money will be needed for the rainy-day fund and SCIF in the second year, but it will almost certainly be some.

You can see the presentation here.

Hold harmless for enrollment declines

During a press conference earlier this week on his summer learning legislation, Moore indicated that traditional public schools could expect to be held harmless for declines in average daily membership. Due to COVID-19, districts around the state are expecting to see fewer students on their rosters, and that can affect funding from the state. Moore is basically saying not to worry about it. Whether his words will translate to actual legislative language remains to be seen.

In a legislative committee on Wednesday, NC Community College System President Thomas Stith also discussed the system’s needs around enrollment declines.

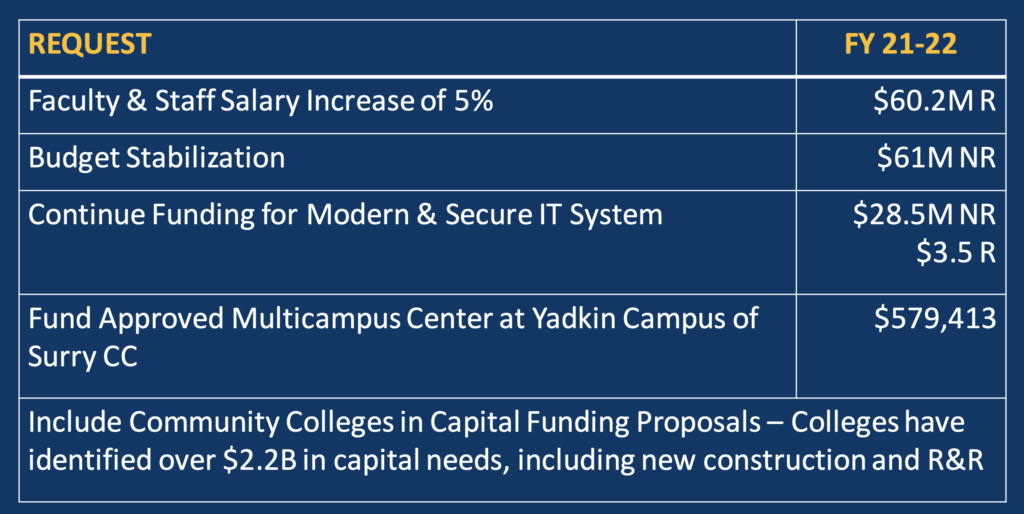

The system is asking for about $61 million for “budget stabilization.” Basically, they’re asking for money to make them whole after community colleges around the state have seen drops in enrollment. Community college funding is also directly tied to student enrollment, but in a different way than K-12 schools. Community colleges receive state funding based on enrollment in the previous year. The funding request would fill the holes in next year’s budget caused by a drop in enrollment this year.

We’ve reported on the system’s budget priorities previously, but this was the first time an actual number was attached to the budget stabilization request.

Program Evaluation Division

The nonpartisan Program Evaluation Division, which is responsible for overseeing government functions, is being disbanded by legislative leaders, according to reporting from WRAL and the News & Observer. WRAL reported that staff in the division were told Monday that they had only two more weeks on the job.

The Division has had numerous reports on education issues over the years, including most recently on teacher diversity.

The Division’s website describes it “as a central, non-partisan unit of the Legislative Services Commission of the North Carolina General Assembly that assists the General Assembly in fulfilling its responsibility to oversee government functions.

“The mission of the Program Evaluation Division is to evaluate whether public services are delivered in an effective and efficient manner and in accordance with the law.”

School sports

A group of Senate Republicans filed a bill this week that would change limits on how many spectators can watch student sports at “outdoor high school sporting venues.” The governor has limited crowds at such events to 100 people via executive order. This bill changes that to “40 percent of an outdoor facility’s capacity.”

According to a press release from one of the bill sponsors, Sen. Todd Johnson, R-Union, they are also separately asking the governor to change his restriction. They sent a letter on Feb. 18 on the issue. If he did that, the legislation wouldn’t be necessary.

The bill title is “Let Them Play and Let Us Watch.”

Cooper was asked about it during his Feb. 18 press conference. He said his current COVID-19 executive order runs out at the end of the month and that he will announce next week what restrictions might be in the executive order that replaces it. He said restrictions surrounding high school sports are “one of the issues that health officials are looking at.”