The COVID-19 pandemic has put affordable child care further from the reach of many North Carolina families, a report from the North Carolina Early Childhood Foundation (NCECF) says. That affects not only child development, the report says, but parents’ ability to work and recover from job losses.

“As with everything else that it’s touched, the pandemic has overwhelmed the nexus between the work that people can do and the child care that they have,” Clive Belfield said on an NCECF webinar last Thursday.

Belfield is an economics professor at Queens College of City University of New York. He’s also the lead author of the report, which estimated a cumulative loss of $2.4 billion annually for North Carolina due to inadequate child care. During the pandemic, that number grew to $2.9 billion, factoring in losses from families, businesses, and state government.

The report, released in December, said many families have left their formal child care arrangements for such reasons as income loss or working from home. That means the percentage of families covered by formal child care has dropped from about a half to a third, according to a representative survey of 802 working parents in October 2020.

“This pandemic has been very disruptive in that it’s basically made child care almost like a disappearing act,” Belfield said.

The reasons are complex, he said. Among the families no longer accessing child care, 28% of respondents said they were not working and could not afford child care, and 33% said they were not working so they did not need child care. Twenty-one percent said they could not find a provider, and 16% said their provider had closed.

“In the sense that child care was unaffordable before the pandemic, it’s now doubly, triply unaffordable and inaccessible,” Belfield said. “In some respects, those two things have worked together, but they’ve basically caused the child care sector to disappear almost.”

Belfield explained that even when parents say they don’t need child care because they’ve lost their jobs, their ability to find another job is affected because they can’t find or afford child care.

A double bind

That puts parents in “a double bind,” Belfield said. Here is an excerpt from the report:

“They cannot find jobs because they cannot access child care; and without jobs, they cannot build the skills and experience that will allow them to afford high quality child care. At the same time, with rising costs of providing COVID-safe child care, parents are further pushed out of the formal child care market.”

This is especially true for families of color, he said, who had lower access to high-quality care even before the pandemic. Workers of color also are less likely to have access to family-friendly workplace policies such as flexible hours and paid leave, and are less likely to be able to telework.

“And so families of color … are not able to make as many work adjustments, at the same time as they need child care that is not available,” he said.

Families living in rural areas also have been disproportionately affected. The survey found the percentage of rural families accessing formal child care had dropped from 44% to 15%. When combining the economic impacts of the pandemic and the lack of child care access, the report found, rural families were in tougher situations than families in cities and suburban areas:

“For the cities, job loss is a big problem but ECE (early childhood education) is available; in suburban areas, job loss is less of a problem although access to ECE might be strengthened. But for rural areas, both work and ECE options have deteriorated. … These two phenomena reinforce each other: it is hard to find work without child care; it is hard to afford child care without work.”

Child care issues, work issues

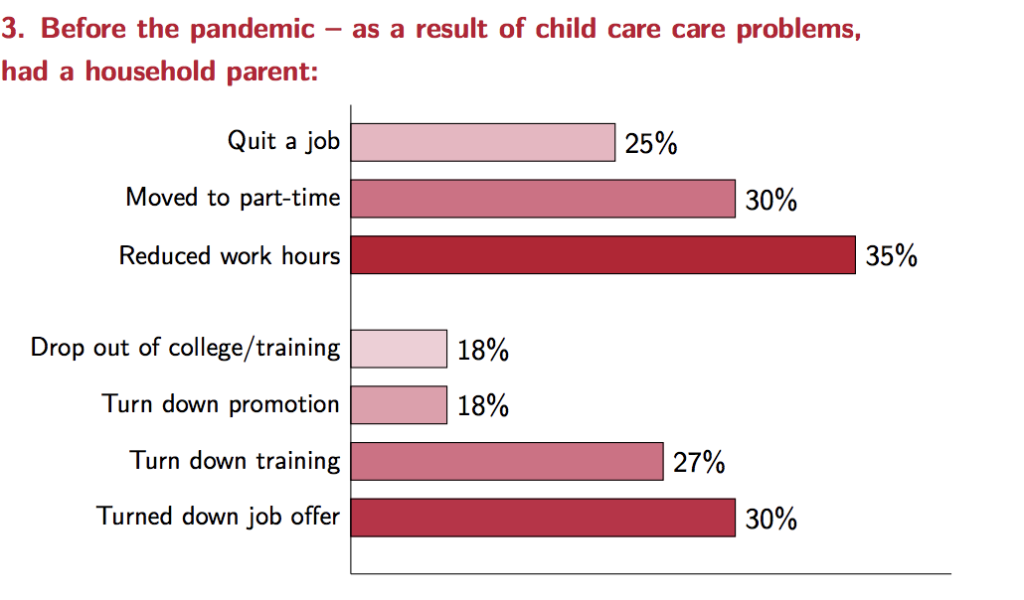

For many working parents of young children, pre-pandemic child care issues caused them to make work changes, such as reducing hours or quitting a job altogether, as well as sacrifices in their career, such as turning down a job offer or training. Of parents in the survey, 35% said they had reduced their work hours because of child care problems, and 25% had quit a job.

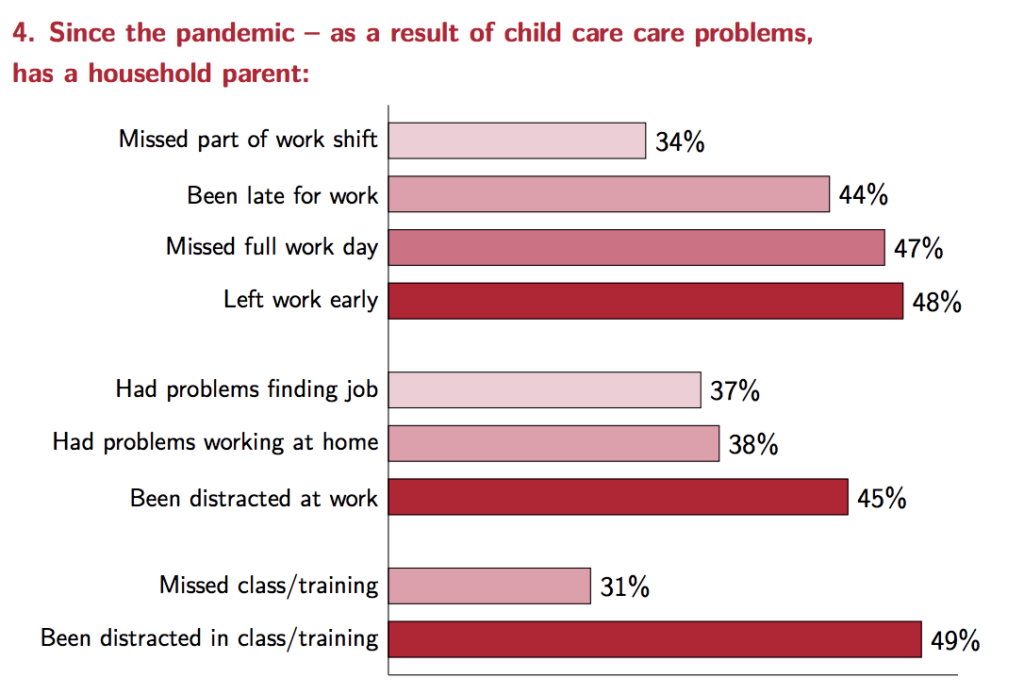

Since the pandemic, the study found new kinds of work disruptions due to child care issues. Forty-seven percent of respondents said they missed a full work day due to inadequate child care. Thirty-seven percent said they had problems finding a job due to child care issues.

Find percentages of parents experiencing different work issues, from finding work to work productivity, before and during the pandemic in the chart below.

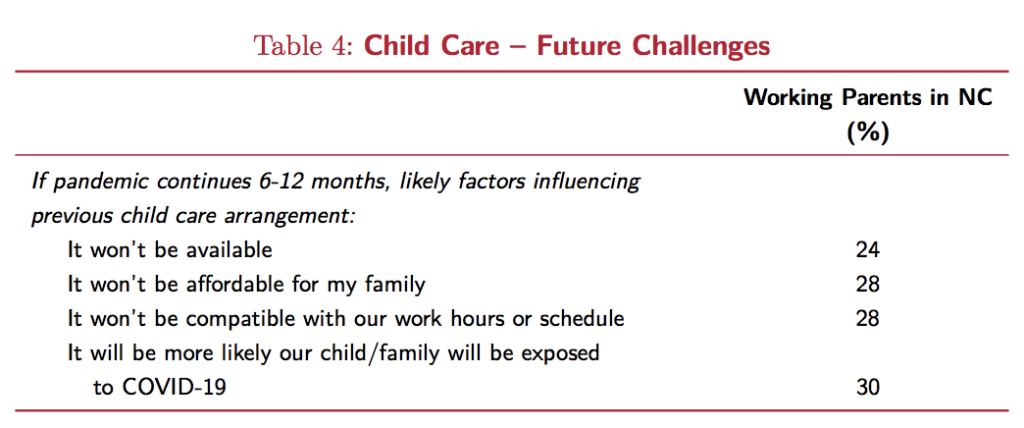

Twenty percent of parents said they were uncertain their child care arrangements would last as the pandemic continues, with four main concerns: availability, affordability, child care working with work schedules, and COVID-19 exposure risk.

What can be done?

Public investment is needed but should be thoughtful and targeted to groups in the most need, said Sherika Hill, research and policy liaison at UNC-Chapel Hill’s Frank Porter Graham Institute, and Sandra Soliday-Hong, a research scientist at the institute. Both were panelists on the webinar.

“If we really aren’t serious about attacking and addressing some of these systems issues of access, inequality, and equity, then these disparities will continue,” Hill said. “It’s just unfortunately that it will happen earlier in the life course if we don’t take the time to address what’s really causing gaps for the people who need it most by supporting families with policies that really seek to benefit everyone equitably.”

Soliday-Hong offered suggestions for equitable investment in the early care and education system in three categories — state and federal funding, workplace improvements for early educators and parents, and private-public partnerships:

State and federal funding

- The state should expand NC Pre-K, the state’s public preschool for at-risk 4-year-olds, while ensuring slots for 4-year-olds don’t take over spaces for infants and toddlers, Soliday-Hong said.

- She called for expansion of child care subsidy assistance and equitable allocation of those funds throughout the state. This program is funded with a mix of state and federal dollars. Parents also would benefit from transition funding, she said, as they fall in and out of eligibility in an unstable labor market.

- She pointed to an opportunity for a system of infant/toddler care similar to NC Pre-K at the state level.

Workplace improvements

- Early childhood educators need higher compensation and benefits, she said. The state should create a data system to track early educator qualifications and match them with appropriate wages.

- Parents need workplace accommodations, set by a combination of employers and state policy, such as paid parental leave and sick leave.

Collaboration between public and private entities

- Soliday-Hong pointed to Head Start models, a federal program for 3- and 4-year-olds from low-income families, that have created partnerships between school districts and private entities to improve quality and leverage community resources.