This week kicks off the next long session of the North Carolina General Assembly. Technically it started a couple of weeks ago, but that was all pomp and circumstance. The real action starts Wednesday, Jan. 27. For a primer on the long session and what that means, read Mebane Rash’s article here.

During this session, lawmakers will take up a number of bills, but their most important job is to pass a two-year budget for North Carolina.

What’s happened?

The last long session in 2019 came just after an election in which Republicans lost their veto-proof majority in the General Assembly. Then, there was a stalemate between the legislature — led by Republicans — and Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper. The consequence was no overarching budget bill, though there were a number of so-called “mini-budgets” that ensured needed funding was allocated.

The short session in 2020 wasn’t much better with no real resolution to the budget stalemate. From an education perspective, perhaps the most significant impact was the fact that teachers received no new teacher pay raise during the last biennium. Teacher pay is always one of the largest chunks of the education budget, so the fact that there was no new raise — as there has been annually for years — is significant. Teachers did, however, get one-time $350 bonuses, as well as the ordinary pay increases they get for increased years of experience.

Further complicating matters last year was the introduction of a pandemic that forced students out of classrooms, shut down businesses across the state, and made many leaders worry about the state’s finances.

Federal stimulus funds have helped the state weather the crisis so far. Additional stimulus money is on the way to North Carolina — $1.6 billion is earmarked for the state’s schools, with the bulk of that money going directly to local school districts. That’s all to be used to combat the impacts of COVID-19. And there is talk from President Joe Biden about another COVID-19 relief plan in the works.

How much money do we have?

But let’s talk about state money for traditional spending. Here is what budgets have looked like over the past few years.

Back in 2017, the General Assembly passed its last two-year budget. That included $9,046,403,622 for the Department of Public Instruction (DPI) in 2017 and $9,425,109,426 in 2018.

In the short session in 2018, lawmakers added an additional $167,847,276 for the Department of Public Instruction.

In 2019, the General Assembly wanted to pass a two-year budget that included $9,857,518,690 for the Department of Public Instruction in 2019,and $10,177,532,330 in 2020.

That last budget, however, was the one vetoed by the governor, so it never went through. We haven’t had a true budget since.

According to the December General Fund Monthly Budget Report — the most recent available — North Carolina has a little over $4 billion that isn’t reserved for any other expenses.

In addition, the state has more than $1 billion in its savings reserve (rainy day fund). But that is money the Republican leaders in the General Assembly typically try to avoid spending.

Complicating the spending picture is the fact that there is no consensus revenue forecast. Typically, this forecast is, in part, what the governor as well as lawmakers use when developing their spending plans. One was supposed to come out in the fall, but never did. According to Lauren Horsch, communications advisor for Senate President Pro Tempore Phil Berger, R-Rockingham, the nonpartisan forecasters at the General Assembly “determined that because of the pandemic the economy was still too unpredictable to produce a reliable forecast.” She said a forecast is expected in February or March.

The problem is this: while the state is in a good position with money in hand, that money is mostly good for one-time expenses. The state needs to know what revenue to expect in order to allocate recurring expenses, something that is essential in a two-year biennium budget.

Dan Gerlach, who served as a senior fiscal advisor to Democratic Gov. Mike Easley, said that revenue has looked pretty good so far this year despite COVID-19 according to monthly budget reports from the state controller’s office.

There are multiple reasons for this, he said, including the change in the tax date last year, quick action by the federal government to send relief funding to states, and the fact that the financial impact of COVID-19 disproportionately impacted low-wage workers who don’t provide as much revenue to the government as others in the economy. Business and sales taxes both look good, he said, which was a concern as the pandemic slowed the economy.

Having said all that, Gerlach said there is still uncertainty.

“We don’t know when the economy is going to recover,” he said. “We don’t know when consumer behavior is going to recover.”

He said the current economic situation isn’t like other recessions. The government can’t just put money in people’s pockets and expect them to go out and spend it. People are, in many cases, afraid to go out and spend due to fear of COVID-19.

Gerlach said that when revenue numbers for January and early February come in, the state will have a better idea of how the state ended up by the end of 2020.

What we do know is that the state is in a better position than experts thought it was in May when the last forecast came out and predicted large revenue shortfalls.

“It’s not the time to be breathing in a brown paper bag about the North Carolina budget situation,” Gerlach said.

What about COVID-19?

A lot of the legislative priorities this session will be influenced by COVID-19.

The North Carolina School Boards Association begins its legislative priority list with a section on COVID-19, asking for waivers and flexibilities, funding for personal protective equipment, internet connectivity, and more.

“LEAs have endured a year of challenges due to COVID-19, unlike any in our lifetime. This pandemic will unfortunately continue to present countless hurdles well beyond the day when it is finally under control,” the legislative priorities state.

These are refrains seen again and again on legislative priority lists from groups around the state. COVID-19 exposed areas where public education in North Carolina is weak, including everything from lack of widespread broadband internet access to below recommended levels of staffing for school nurses, counselors, and resource officers.

According to experts at the right-leaning John Locke Foundation, broadband internet access and remediation for learning loss are two of the big issues that legislators will likely have to grapple with this session.

Last March, the pandemic closed school buildings, and while some students have been able to come back to classrooms in some way, shape, or form this year, the business of educating has been disrupted by COVID-19.

Former Rep. Craig Horn, R-Union, said last year that North Carolina students were losing a year of educational progress thanks to COVID-19, a statement that received some pushback from critics.

But regardless of the exact amount of learning lost, it’s not controversial to say that school has been anything but business as usual since COVID-19 hit.

Terry Stoops, director of the Center for Effective Education at the John Locke Foundation, cited remediation of learning loss as the single most important issue for lawmakers to tackle.

“There is no greater priority than providing remediation to students who received substandard instruction during the pandemic,” he said in an email. “Lawmakers should support innovative, equity-focused ideas, such as programs that allow parents of struggling students to access a voucher or education savings account to use at the public, private, or nonprofit educational provider of their choice.”

Becki Gray, senior vice president of the John Locke Foundation, however, wrote an entire piece pushing broadband as the top priority for lawmakers.

She said the issue was always an important one, but its necessity became all the clearer after COVID-19.

“But with the pandemic, the broadband access problem became acute, as schools went to all online learning, employees were working from home, health care via telehealth was safer and more convenient, and online commerce soared. Access to broadband is no longer a luxury; it’s a necessity,” she wrote in this piece for The Carolina Journal.

These priorities are ones shared by others as well. Both learning loss remediation and broadband make the legislative priority list of the North Carolina Association of School Administrators. Broadband is on the list of myFutureNC’s policy recommendations, and the North Carolina School Boards Association has learning loss on its legislative agenda.

One of the principal ways the General Assembly has been addressing broadband internet access is through the Growing Rural Economies with Access to Technology (GREAT) program which seeks to expand broadband in rural parts of the state.

The News & Observer recently referenced Rep. Dean Arp, R-Union — a cosponsor of the legislation that launched the GREAT program — as saying more funding for GREAT grants is probable this session. According to the article, Arp said that the demand from the latest application period was upwards of $64 million, but the program only has $30 million available.

You should also expect to see policy change on hot topics such as early childhood education and literacy via the Science of Reading this session. These are issues that lawmakers revisit again and again, but this year they could see even more movement thanks to the impacts of COVID-19.

EducationNC’s Rupen Fofaria and Liz Bell wrote legislative previews focusing on these two areas.

Who’s asking?

The State Board of Education and Department of Public Instruction are the ones most chiefly responsible for public education at a statewide level. As such, it’s important to pay attention to what they’re asking lawmakers for.

This year, the Board and the department are working in a more cooperative manner than in years past. This month, Republican Catherine Truitt took the reins of DPI, and during her first meeting of the State Board, she made clear that she and the Board will be working in tandem.

As such, the State Board has delayed a detailed look at its legislative priorities until Truitt and her team can have a chance to review them and weigh in.

In December — prior to Truitt taking over DPI — the Board heard a presentation on potential priorities for consideration that would have required about $514 million from state lawmakers.

Those tentative line-items included:

- Almost $5 million for early grades reading

- More than $143 million for teacher preparation, professional learning, and pay

- More than $27.5 million for principal preparation, professional learning, and pay

- More than $208 million for student mental health

- Almost $82.5 million for school and district turnaround assistance

- A little more than half a million for School Accountability and Teacher Effectiveness Models

- More than $10 million for “Connecting High School to Postsecondary and Career Opportunities”

- More than $2 million for state Department of Public Instruction support positions

- More than $34 million for “Other Agency Budget Requests”

Those numbers and priorities were removed from the presentation for January — after Truitt officially became superintendent — and were replaced with a more high-level look at State Board priorities.

The Board is meeting on Jan. 27, the same day legislators come back. They will likely look at a more detailed listing of priorities along with specific funding asks at that time. Here is the agenda.

Who else is asking? Principals and teachers

As mentioned above, teacher pay is always a big deal in any General Assembly session.

Joseph Kyzer, a spokesperson for House Speaker Tim Moore, R-Cleveland, said that North Carolina shouldn’t have as much money on hand as it does, and he attributes part of that to a lack of a teacher pay deal in the previous two sessions.

“That should have gone to education,” he said in an interview before Christmas.

In an interview with EducationNC, Berger said that the General Assembly has already shown a “commitment to addressing issues having to do with compensation for our educators,” and also noted that lawmakers tried to pass pay raise legislation that was vetoed.

On whether teacher pay raises will be coming this session, he said: “I think it would be up on the priority list in terms of any expansion dollars that we might have the ability to commit.” He went on to say that teacher pay will continue to be a priority.

Teacher pay is part of the legislative agenda of multiple education advocacy organizations as well. And there might be less strife between legislative Republicans and Democrats this session on this and other subjects. Berger said that there has been more direct contact between him and Gov. Cooper of late.

“I think everybody’s saying the right things,” Berger said. “And, you know, we will see as time moves on how much success we’ll have in finding that common ground and working on things that we all profess to believe are the right things to do.”

It’s important to note that the disagreement between legislative Republicans and Cooper in 2019 wasn’t about whether to increase teacher pay, it was about how much to increase it. Cooper wanted a 9.1% average pay raise, and legislative Republicans wanted a 3.9% raise.

Teacher salaries are one of the single biggest expenses for the legislature. According to Philip Price, a former chief financial officer for the state Department of Public Instruction, each percent increase in pay for teachers amounts to something like $60 million. So negotiations over teacher pay aren’t small stakes.

Principal pay is another important topic that comes up often during budget talks. Shirley Prince, executive director of the North Carolina Association of Principals and Assistant Principals, said principals are looking for more pay and reforms to the principal pay schedule this session.

The principal pay schedule as it stands gives base pay to a principal based on the size of their school, and then gives extra pay if that’s principal’s school meets or exceeds growth. Prince said principals would like to see years of experience added in to the salary calculation and less emphasis on academic growth. She said performance bonuses are good, but should be “the icing on the cake. It shouldn’t be the meal.”

Additionally, she said principals want the principal pay schedule aligned with teacher schedules. Basically, they say principals should get paid based on their years of experience on the teacher pay schedule, and then they will get an extra percentage on top depending on whether they are principals or assistant principals.

This will add back in years of experience to the calculus as well as ensure that principals gets paid more than their assistant principals, and that both kinds of administrators get paid more than their teachers. Currently, some principals have to be paid on assistant principal or teacher salary schedules so that they don’t make less than the people they oversee, according to Prince.

What about Leandro?

The Public School Forum of North Carolina will hold its annual Eggs and Issues event on Jan. 28 this week, at which point it will unveil its top education issues of 2021. Last year, it picked the long-standing legal case Leandro as its only issue, a break from its long tradition of announcing a “top 10” list.

Leandro is likely to continue to be a big issue this year.

The Leandro case started in 1994 when families from five low-wealth counties sued the state, claiming North Carolina was not providing their kids with the same educational opportunities as students in higher-income districts. In 1997, the state Supreme Court ruled unanimously in the case that the state’s children have a fundamental right to the “opportunity to receive a sound basic education.” A later state Supreme Court opinion agreed with a lower court that North Carolina had not lived up to that constitutional requirement for every student.

Here is a video explaining Leandro.

Both sides in the Leandro case agreed back in 2017 that an independent consultant should be chosen to make recommendations on how the state can ensure quality education for every North Carolina child.

That consultant was WestEd, and the organization released a report in late 2019 that laid out how the state can ensure that all students in North Carolina have the opportunity for a “sound basic education.”

A consent order followed, signed by Judge David Lee, that lays out the general agreement of all parties as to the facts of the case, the findings and recommendations of the WestEd report, and the need to do something further to meet the Leandro mandates. It also establishes a plan for the parties to present further reports detailing concrete steps the state will take to meet the short-, middle-, and long-term recommendations of the WestEd report.

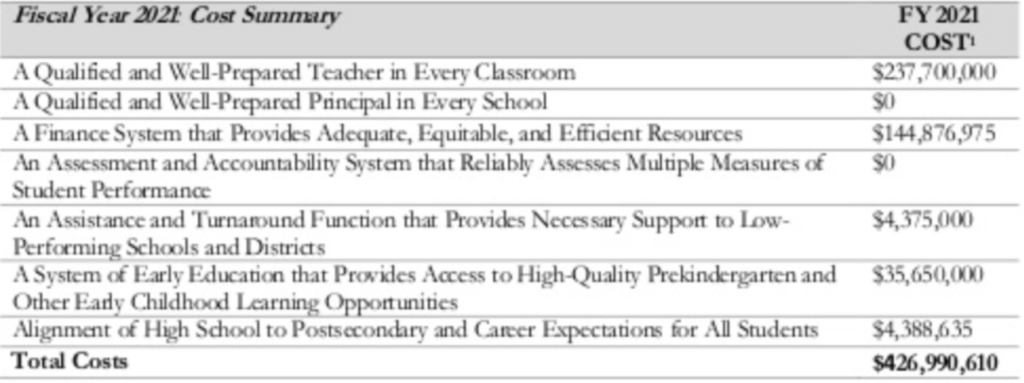

In September, Lee adopted a 2021 plan for meeting the Leandro mandate. It included money for teacher prep and pay, early childhood education, improving low-wealth schools, and more. Here is a chart that covers some of the areas covered in that plan and the suggested funding levels.

Here is the plan in its entirety.

The state Department of Public Instruction and State Board of Education have also identified Leandro as an important component of their work, going so far as to appoint Bev Emory to oversee the department’s efforts to implement the reforms necessary to meet Leandro’s mandates.

Additionally, Leandro is a component of multiple legislative agendas from education advocacy organizations in the state. So, expect Leandro to be part of the conversation this session.

What else should you look out for?

Another issue that will be getting attention this session is retirement benefits for new hires. Back in 2017, lawmakers made a decision that is just now coming home to roost. They got rid of retirement health benefits for teachers hired in 2021 and beyond.

There are concerns that the loss of this benefit could make it even harder to recruit and retain teachers, something that is always a challenge in North Carolina and around the country.

Expect to see this be part of the discussion.

And another big issue this session is likely to be school construction.

Back in 2019, there was a push to find money to help fund the school construction needs in North Carolina. The big division was between the House and the Senate, with the House favoring a school construction bond and the Senate looking for a pay-as-you go approach.

The final budget compromise would have provided about $4.4 billion over 10 years for K-12 school construction and repair via the pay-as-you go approach, but Cooper vetoed it, in part because he favored the bond proposal.

And then in 2020, COVID-19 and economic uncertainty made the prospect of finding the money for school construction even more unlikely.

Unfortunately, that may still be the case now.

In an interview with EducationNC, Berger said that uncertainty about revenue continues to make the picture murky. Also, transportation infrastructure and capital needs in other areas could pull the attention of lawmakers away from school construction, he said.

“I’m sure there’ll be a lot of talk about (a bond),” he said. “I’m not sure what we’ll be able to do.”

COVID-19 has also shone a brighter spotlight on other perennial issues that have had trouble getting a foothold in North Carolina. For instance: school calendar flexibility.

The state mandates two things when it comes to school calendars: how many days students must be in school and when districts can start and end their calendars.

The state says that students must be in school for a minimum of 185 days a year or 1,025 hours of instruction. It also says that schools can’t start earlier than the Monday closest to Aug. 26, and they can’t end later than the Friday closest to June 11.

As it turns out, this creates a host of problems for our geographically diverse state. From snow to hurricanes, schools are often forced to close school and then jam in make-up days at odd times in order to fit within the legislative calendar mandate. Districts argue they need calendar flexibility — the ability to start and stop school given local considerations — to avoid extreme measures sometimes needed to get kids the instruction that is mandated.

There is large-scale bipartisan support for calendar flexibility, but advocates say that the tourism industry holds up legislation because businesses that rely on student workers over the summer don’t want districts to cut into their season.

With COVID-19 and its disruption of traditional school schedules, expect to see more education advocates pushing for flexibility for schools and districts.

You also might see some discussion about class size flexibility this session. This has been a controversial topic for years since lawmakers started pushing for more stringent limits on how many students can be in one class. The General Assembly has phased in class size limits over time rather than mandating them all at once. This school year, for K-3, the average class size can only be 18 students.

Rep. Kevin Corbin, R-Cherokee, spoke on Education Matters this week about class size restrictions and some issues they raise.

In one of the counties he represents, Macon, he said there is a relatively small K-12 school that illustrates the problem with the mandate.

The school has about 20 kids each in kindergarten, first, second, and third grade. But because of class size limits, he said each of those grades has to have two teachers for about 10 kids per classroom. And the state doesn’t pay for the extra teachers, so the county has to pick up the tab.

“What happens is in Macon County Schools, we fund about 25 or 26 locally paid teachers at about $50,000 plus per teacher,” he said. “And that’s local money. So that’s unfair.”

Kyzer, a spokesperson for House Speaker Tim Moore, R-Cleveland, said lawmakers can take into account circumstances like Corbin is describing when it comes to implementing class size. But he said this is something the General Assembly wants to see done.

Additionally, between COVID-19 relief going directly to districts, the large amount of cash the state has on hand, and potentially other funding lawmakers could allocate from COVID-19 relief available to them, there are plenty of funds available to make lower class sizes a reality, he said.

“The General Assembly has compromised and pushed this out, so schools systems have known the change is coming,” he said, adding later. “We feel strongly we have provided the funds and the framework, and this is something that everybody prioritizes.”

These are just some of the big items you should expect to be hearing about during this long session. Stay tuned to EducationNC for coverage as lawmakers get to work in the months ahead.

Editor’s note: Craig Horn and Shirley Prince serve on EducationNC’s Board.