Ten years from now, North Carolina might not have 58 community colleges anymore. That’s if enrollment trends continue on pace, according to Peter Hans, president of the North Carolina Community College System.

During a two-day planning session, the State Board of Community Colleges took a deep dive on community college data and issues facing the system. Enrollment was a through-line in much of the conversation, particularly on the first day.

Board Chair Breeden Blackwell said there needs to be a change in thinking in the system.

“Elected officials…are not going to let you sit out there with empty classrooms and empty colleges,” he said.

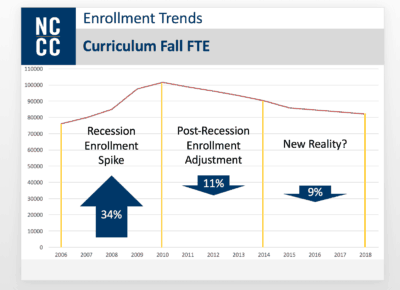

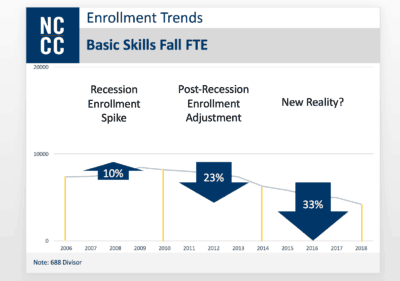

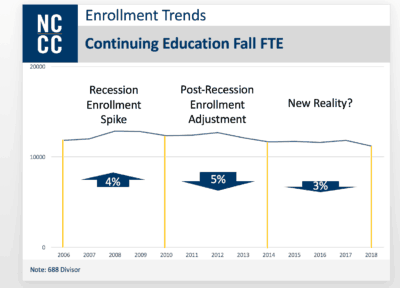

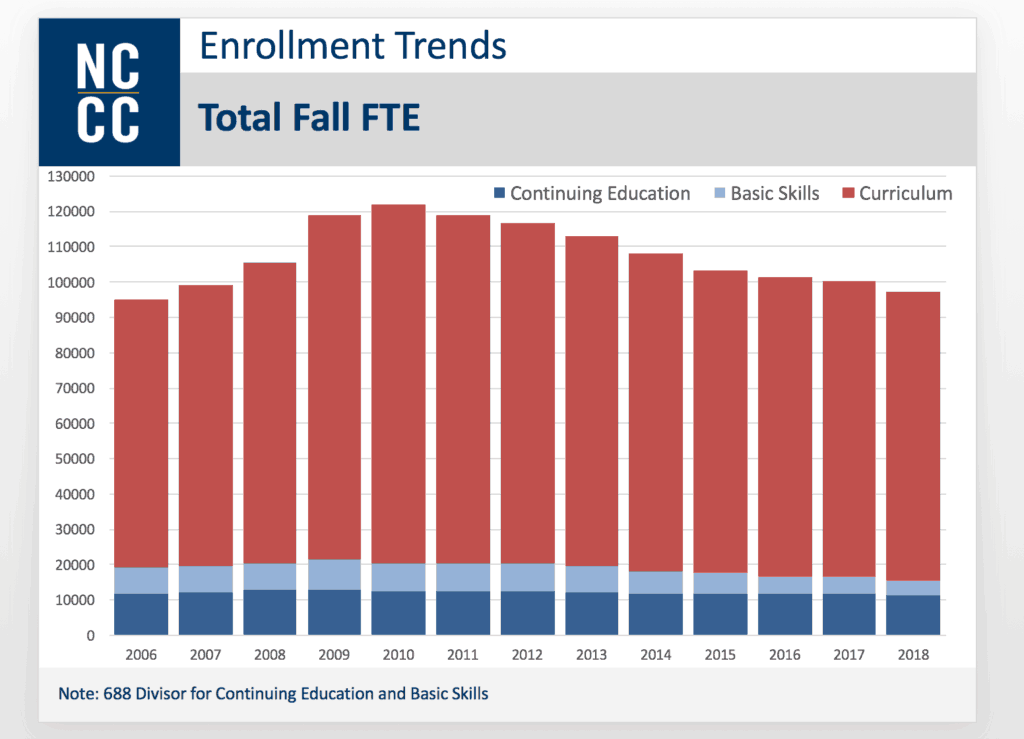

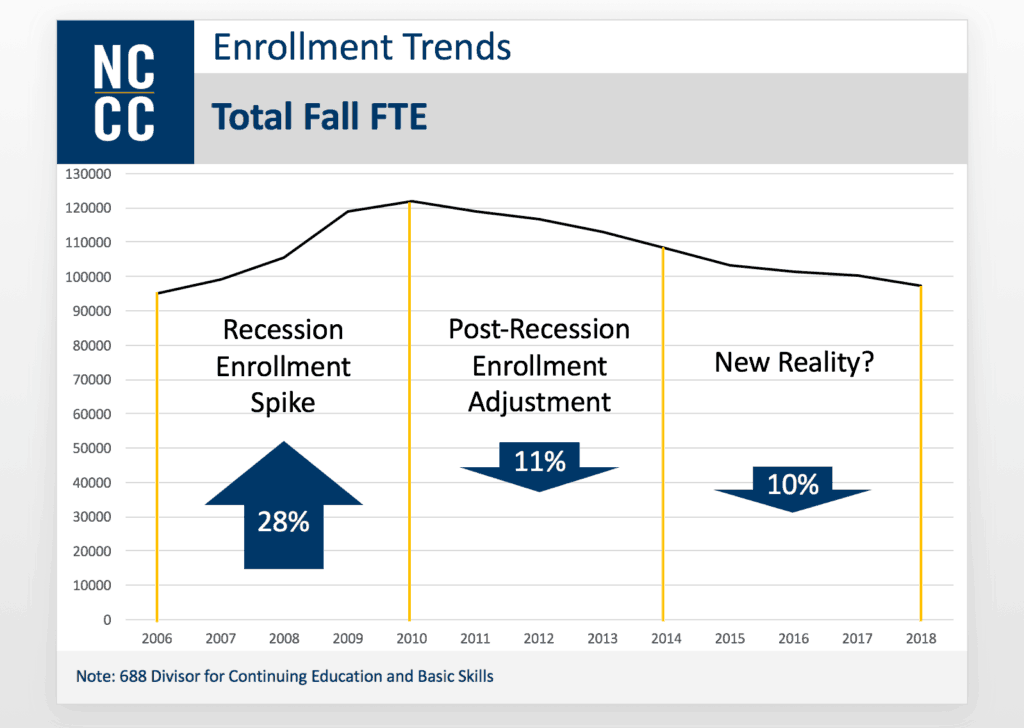

The enrollment trends are clear. In the lead up to and during the recession, enrollment was on the incline, peaking in 2010. Ever since then, it’s been a steady decline.

Community colleges saw a 28% bump in enrollment from the recession, but an 11% decline afterwards. For the past four years, the decline has hovered around 10%.

And those numbers hold true for every area of the community college system: curriculum, basic skills, and continuing education.

“There are a lot of challenges, especially looking in the more rural parts of our state,” said Bill Schneider, associate vice president for Research and Performance Management in the Community College System.

The rural parts of the state are seeing big projected declines compared to some of the more urban areas of North Carolina, Schneider said.

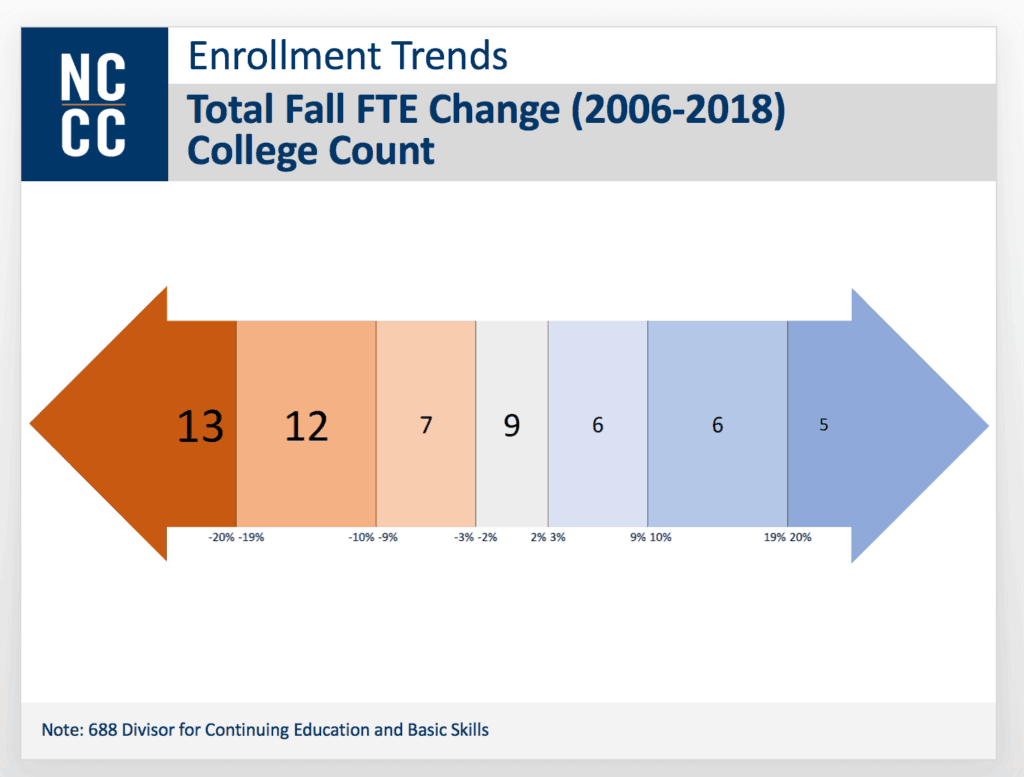

The following chart shows the numbers of community colleges facing declines versus the ones facing growth. The balance tilts towards decline.

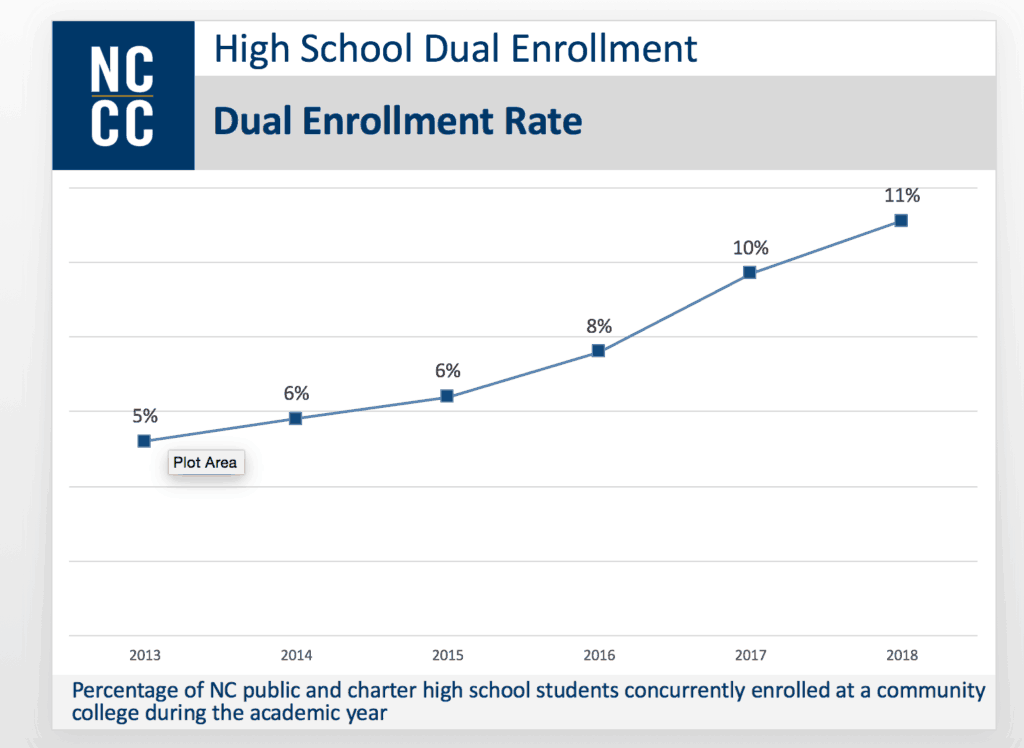

The bright spot in enrollment trends comes in the form of dual enrollment: high school students who are also enrolled in community college. That number has seen a steady increase since 2013.

“In some of our more rural areas, we’re seeing a much higher proportion of high school students who are dually enrolled,” said Dr. Ashley Sieman, director of Program Evaluation Research and Performance Management at the Community College System.

She said the growth in this area in rural parts of the state rather than urban is likely due to the fact that students in urban areas have better access to things like AP courses and other opportunities.

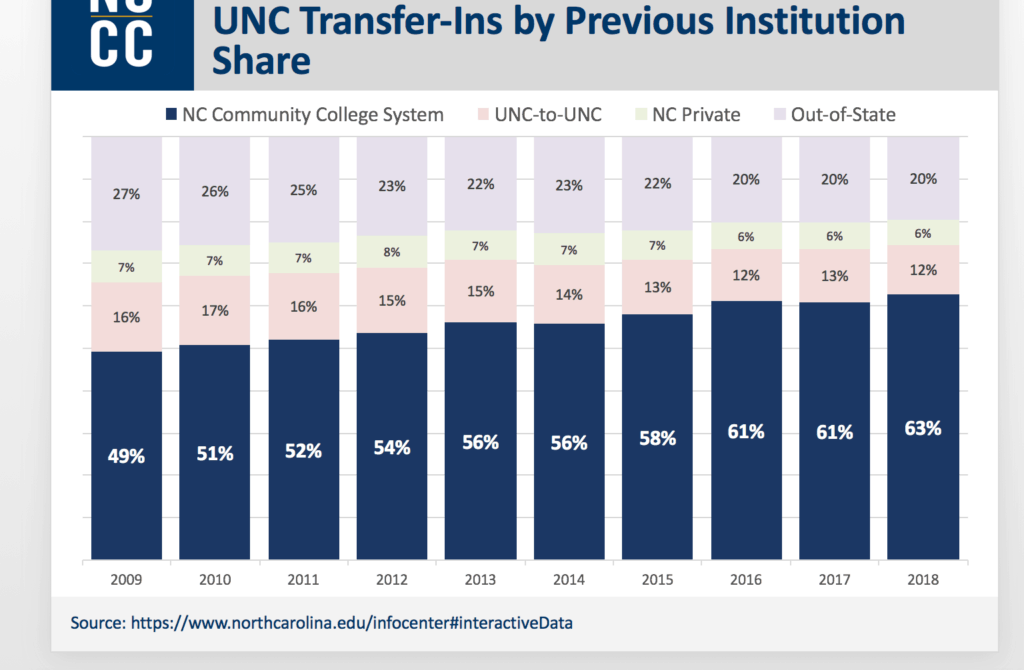

While enrollment trends may be down at community colleges, system schools remain the largest feeder of students to UNC System four-year universities, and that percentage has steadily grown.

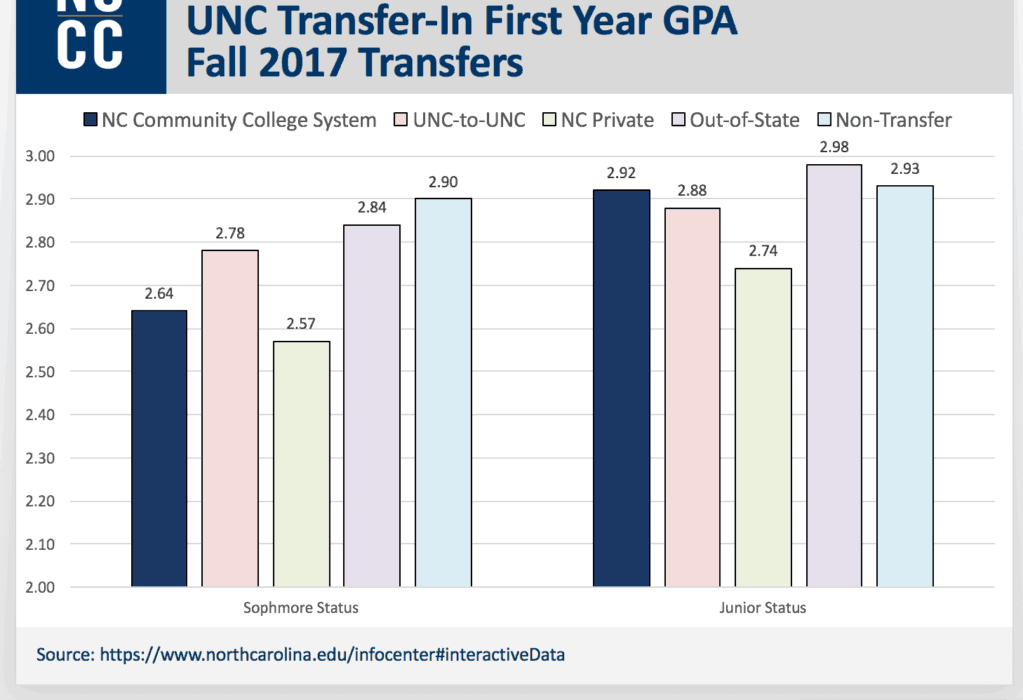

And, compared to students who started at a four-year university, community college students do well when they transfer, particularly if they transfer with their first two years of college complete.

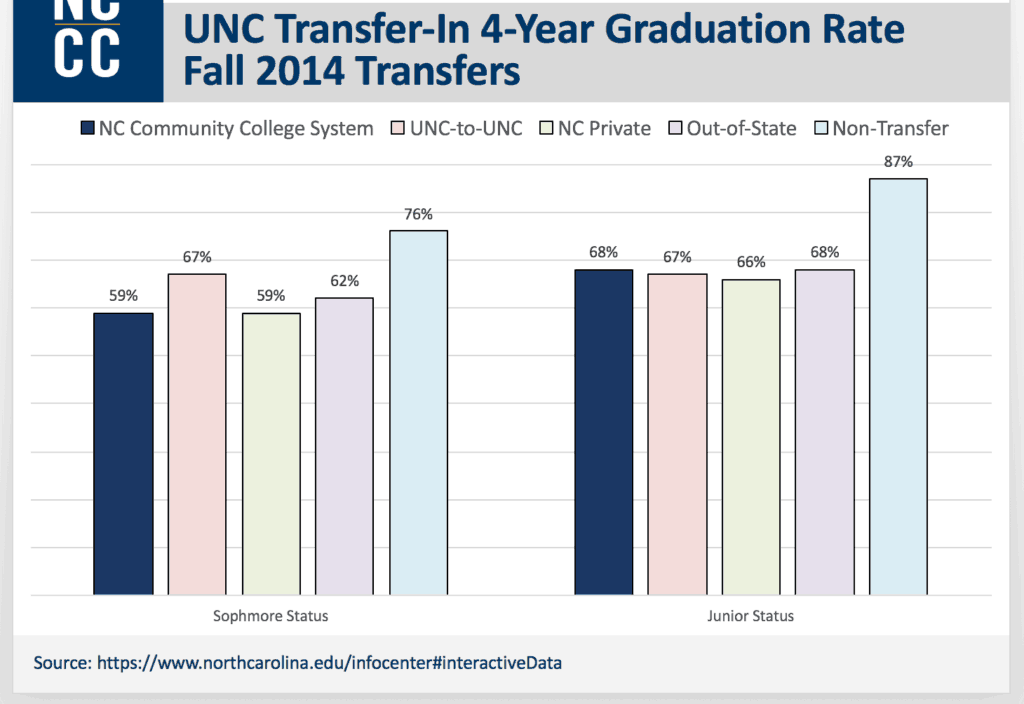

The numbers are a little less encouraging when it comes to the four-year graduation rate. Students who began at a four-year university outperform students from all other avenues of entry.

“As you can see from the info that we’ve received today, we have some challenges ahead of us,” Blackwell said.

He talked about the creation of a new enrollment task force the board created, headed by former board chair Scott Shook.

Shook said that part of the issue with enrollment trends is that population is shrinking in some areas of the state, particularly rural ones. The target demographic of community colleges — those around ages 18-25 — is decreasing with it.

“It hit me that there’s 57% of our colleges in areas where that demographic is going to shrink,” he said.

Shook gave the example of Martin County, where a hospital recently closed its neonatal unit because there weren’t enough births in the county to support it. Those children not being born won’t go to elementary, middle, or high school, and won’t go on to community college.

The enrollment task force brings together a number of people, including community college trustees and presidents, as well as outsiders with interest in the future of the community college system.

The task force is in early days, but Shook said that regardless of what it recommends, the goal is to make sure that community colleges, in some way, shape or form, are providing a high-quality education to people within a 30-mile radius.

While population is one area the community college system needs to address, another is simply the push to get more eligible students to attend and complete community college. During the planning session, Hans discussed his role in myFutureNC and its educational attainment goal of 2 million 25- to 44-year-olds with a high-quality postsecondary degree or credential by 2030.

Today, he said, only 49% of North Carolinians have a postsecondary degree or credential. By 2020, next year, two-thirds of jobs will require those degrees.

Given current trends, Hans said that North Carolina will be short of its 2030 goal by about 400,000 people.

He turned to the topic of the “leaky pipeline,” a metaphor that explains why students aren’t making it all the way through the postsecondary education system.

Take 100 ninth graders, he said. Twenty-five will have a degree or credential in six years. Twenty-four will get some college but no degree. Twenty-two want to pursue a degree or credential, but never do. Fifteen go straight into the workforce or armed services out of high school. And 14% drop out or delay pursuing a degree or credential.

To hit the 2 million mark by 2030, Hans said it would require all sectors of postsecondary education — public and private universities, and community colleges — to increase their completion rate by 53%.

“Do we think public and private universities are going to grow that much in the next 10 years? Or should? No,” Hans said.

A large bulk of that increased completion rate is going to have to come from community colleges.

“The point here is folks, there is a statewide efforts that has bipartisan support, spans across political, educational, and business entities that are coming together to say we know what the state needs to do,” Hans said.

Part of the task of getting more students in and through community colleges is changing the way people look at the schools.

Peyton Holland, executive director of SkillsUSA, told the board that when he went into high school, he was excited because he had the option of taking courses such as masonry, carpentry, and horticulture. His father, a man full of curiosity for learning new things but with only a high school education, instilled in Holland an interest in these kinds of skills.

But in high school, Holland was advised that he needed to look at AP and honors courses because he should be pursuing a four-year degree.

“We heard that at every turn… very rarely did anyone ever ask us, ‘Hey, what do you want to do when you graduate?’” he said.

SkillsUSA is described by its website as a “partnership of students, teachers and industry working together to ensure America has a skilled workforce.”

Holland said his organization’s mission is important, because since the 1970s and ’80s, youth have been told that they need to “work smarter, not harder,” and pursue a four-year degree.

“That’s the message that has permeated our country for the last four decades,” he said.

In the United States, he said 1.9 million students will get a four-year degree and 41% are going to work for a job that doesn’t require it.

“They’re not going to be unemployed, but guess what, they’re going to be underemployed,” he said.

The average college graduate stands to make an average of $47,000 upon graduation. But if they’re underemployed, they’re more likely to make around $37,000, he said.

Meanwhile, students are accruing trillions of dollars in student debt.

Holland said that for every job that requires a master’s degree, there are two that require a bachelor’s, and seven that require a two-year apprenticeship or advanced technical training.

He pointed out that the largest graduate school in North Carolina isn’t at a four-year university. It’s Wake Technical Community College, where more than 20% of enrollment comes from people who already have four-year degrees.

One big issue Holland sees is that the nation has created what he called an “educational caste system,” where a four-year degree is seen as the gold standard and community college is seen as sub-par.

“We’ve really got to change the conversation,” he said. “It’s not about this degree or that degree…education is education.”

The community college system is already thinking about how to address enrollment issues and has even launched a marketing campaign targeting young potential community college students.

Hans said he invited Holland to come speak to the board because of the historical imbalance between short-term workforce training at community colleges and the curriculum programs that students use to transfer to four-year universities.

“Career Technical Education is not always perceived the same way necessarily as university-related programs,” he said, adding later: “It’s hard to say that we’ve had these on an equal plane.”

He said that the system has had far more emphasis on college transfer paths than short-term workforce training. And this goes all the way to the state’s coffers, which only provide community colleges two-thirds the funding that curriculum programs get. The budget — still stuck in a standoff between Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper and the Republican-led General Assembly — would bring that funding to equal status.

“This is a huge breakthrough,” Hans told the board. “It’s absolutely critical.”

Data from the short-term workforce programs is also more difficult to come by than it is for curriculum programs, making it harder for the system to get a solid grasp on what’s happening with those students. Money in the budget for IT related to short-term workforce would help the system understand these programs better.

Meanwhile, short-term workforce training will perhaps always be at a disadvantage to curriculum. For instance, students going into short-term workforce training aren’t eligible for financial aid.

Focusing more on short-term workforce training is important for the community college system, Hans said, because colleges are incentivized to do more or less with a program depending on the emphasis placed on it.