The first thing teachers and administrators of North Carolina’s laboratory schools would have you know is that they are not carelessly experimenting on children.

Created by the General Assembly in 2016 and envisioned as a partnership between local school districts and the UNC system, lab schools are designed to identify strategies to improve performance at struggling schools while creating opportunities to better prepare prospective teachers for their careers in the classroom. There are five lab schools currently in operation with UNC Charlotte slated to open a sixth this fall. UNC system institutions operate the traditional public schools with charter-like flexibility. Supporters believe lab schools offer a win-win for the state: innovating to help students who are struggling in school, while simultaneously helping to address challenges in teacher preparation and retention.

And while those supporters do hope the program creates laboratories for innovation, they admit the moniker of this legislatively-mandated program can be misleading.

“This is freedom and flexibility combined with knowledge and expertise. We’re not using it in a vacuum,” says Christina O’Connor, the co-director of the Moss Street School Partnership, a nearly 400-student elementary school in Reidsville, which is run as a lab school through a partnership between UNC Greensboro and Rockingham County Schools. “We’re not experimenting on kids,” she says.

O’Connor and other lab school administrators believe the program has the potential to be transformational for struggling students—and to offer a model for other North Carolina public schools to follow to achieve similar successes. But policy questions linger, even as the number of lab schools is set to nearly double.

When the General Assembly passed the state’s budget in 2016, the appropriations bill included a provision creating the lab school program. At the time, the legislature directed the UNC system to create and operate eight lab schools across the state. The statute was subsequently updated to nine campuses, and the General Assembly has continued to tweak aspects of the lab school program, including the deadline to have all nine campuses operational, during the last few sessions.

The original legislation was envisioned to establish lab schools in low-performing districts, requiring that at least 25% of the schools in a particular district be considered low performing in order to qualify for the creation of a lab school. But lawmakers later created a waiver process for this requirement.

Supporters say the underlying goals of the program remain the same: “The mission of a laboratory school shall be to improve student performance in local school administrative units with low-performing schools by providing an enhanced education program for students residing in those units and to provide exposure and training for teachers and principals to successfully address challenges existing in high-needs school settings,” the statute says. “A laboratory school shall provide an opportunity for research, demonstration, student support, and expansion of the teaching experience and evaluation regarding management, teaching, and learning.”

The UNC system, then led by President Margaret Spellings, was bullish on the program.

“We’re really addressing three of the biggest challenges in public schooling in North Carolina,” said Sean Bulson, a former North Carolina schools superintendent and the UNC system official overseeing the lab school program, during an interview in 2018. (Bulson has since moved on to a superintendent job in Maryland.)

Bulson was especially excited about the collaboration between universities and public schools because of the opportunity to provide real world learning for prospective teachers, principals, and other education professionals.

“Unquestionably, one of the most important outcomes of this is for our university folks to experience the reality of our schools a little more directly than they may have in other settings,” he said.

In addition to the stated goals of the lab schools—improvements in student performance and innovation in teacher and principal preparation—supporters also say there’s economic upside to a successful lab school program and a positive return on the state’s investment.

“Every time a child is educated, that’s a plus for the economy,” said C. Philip Byers, who chaired the UNC Board of Governors subcommittee on lab schools, at a meeting last year to approve plans for three additional lab schools. “Our legislators so often look at how does the taxpayer benefit. This is going to be a tremendous benefit to the taxpayer.”

Not everyone is so certain.

Critics—from the North Carolina Association of Educators to academics to Democrats in the General Assembly—question elements of the lab school program, including the way in which schools are selected, the charter-like flexibility granted to the campuses on requirements such as teacher licensure, and the methods for measuring the program’s success.

“This is a trainwreck waiting to happen,” UNC professor emeritus Stephen Leonard, who chaired the UNC system’s Faculty Assembly, told NC Policy Watch’s Billy Ball early last year. He contended that the lab school program was thrust upon the university system with neither the funding nor oversight necessary for success. “It is badly designed, badly funded and badly implemented,” Leonard said. “And that’s not good for anyone, particularly the students.”

The success of lab schools appears to be predicated on the quality of the partnerships among the university, school system, and community. When the legislature established the lab school program in 2016, the first two schools created were the ECU Community School, an elementary campus in Pitt County run by East Carolina University, and the Catamount School, a middle grades campus in Jackson County run by Western Carolina University. Those programs began operating in 2017-18. Three additional campuses opened this school year: the Moss Street school; Academy at Middle Fork, run by Appalachian State University in Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools; and D.C. Virgo Preparatory Academy, run by UNC Wilmington in New Hanover County Schools. Other lab schools, including a collaboration between UNC Charlotte and Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, will open in 2019-20.

From the outset, Western Carolina pulled together a broad group of community stakeholders to discuss how they would work as a team to make the school successful.

“We are in partnership together,” says Kim Winter, the dean of Western Carolina’s School of Education and Allied Professions. “These students are coming out of Jackson County and into our school, and they’re leaving us with our hope of being successful back in Jackson County.”

Those initial stakeholder meetings were important to setting the tone of the working relationship between WCU and JCPS. “It has helped us navigate our local partnership with Jackson County very well,” she says. “Our goal is to create a successful context for those students.”

Similarly, the Moss Street School Partnership, run in Rockingham County by UNC Greensboro, needed buy-in from a wide array of stakeholders as it opened its doors this school year.

“We had a lot of work to do to build trust,” O’Connor, the school’s co-director, says. Although UNCG faculty were already engaged in the region’s public school systems, she says, “it’s different when you are in charge.”

A successful start required intentionality, says Randy Penfield, the dean of UNC Greensboro’s College of Education. “We’re going into a community that doesn’t really know us.”

Because of a strong partnership with Rockingham County Schools, which helped bring community stakeholders together, Penfield and O’Connor say the launch of Moss Street school was a success. “The community feels invested in the school,” O’Connor says. “They feel it is as much their school as UNCG’s.”

While the foundation of lab schools is the same—the enabling legislation and governance by the UNC system—each campus is distinct.

Nestled in the splendor of Sylva’s mountains, the Catamount School shares a campus with Smoky Mountain High School. “We serve a specific population,” says Chip Cody, the school’s principal, who previously led an intermediate school in Buncombe County.

“We’re able to really focus on those students and kind of eliminate the falling-through-the-cracks for some of them with the focus on the whole child and the social, emotional, and academic learning of each student.”

Many of the students are experiencing academic failure or are at significant risk of doing so.

“Most, if not all of our students come to us with an adverse childhood experience,” Winter says. “There are just a whole host of reasons why students aren’t making the growth or progress that any of us would like to see them make. That’s part of our goal as a school is to create innovations that might bring success for them in school.”

From the outset, WCU decided to keep the learning environment at the Catamount School very small. The school currently serves 56 students and is set to grow to a maximum of 75. Classes never exceed 25 students.

“We don’t believe you can create these constant innovations for success that we’re tasked to create in a gigantic school with 700, 800, 1,000 students,” Winter says. “Our task as a laboratory school is to be filled with innovation in all kinds of different areas, and we believe strongly that you’ve got to stay small to be able to focus and do that.”

The small class size enables the Catamount School to think about the curriculum in different ways, Winter says. For example, all eighth grade students take eighth grade science as well as ninth grade earth and environmental science, with the goal of going into high school with a full science credit ahead of schedule. Last year, 92% of Catamount School’s eighth grade students were able to do so.

Other schools are larger and choose to innovate in different ways. The ECU Community School has a modified calendar, serving children until later in the day in order to provide additional time for academic intervention.

One constant across lab school campuses, however, is the desire to bring the resources of the host university to bear for the benefit of the public school students.

ECU involves students and faculty from its medical, dental, and nursing schools and its social work program to enhance the social-emotional wellness of its students. Catamount School students can often be found on the Western Carolina campus, just two miles down the road.

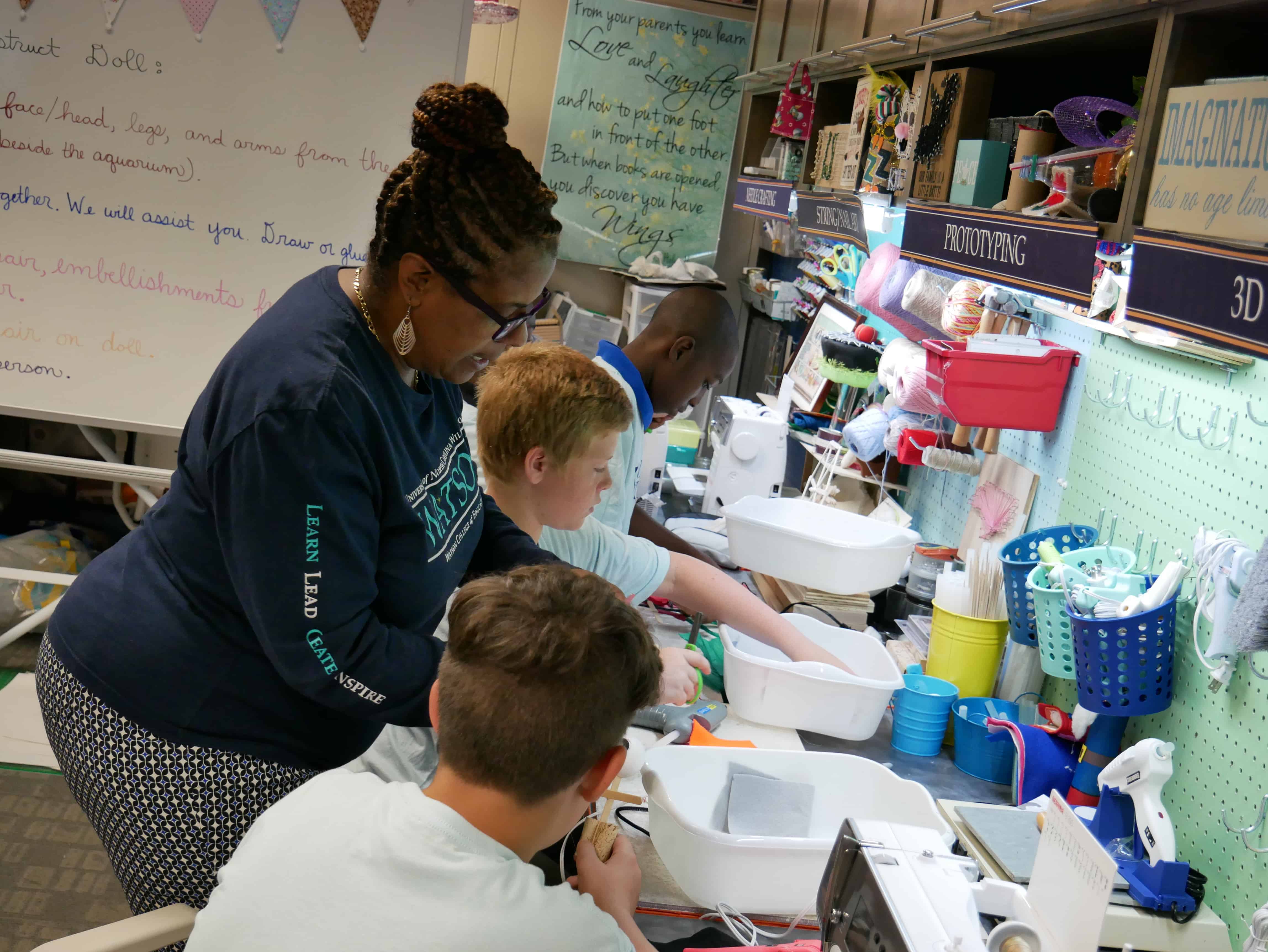

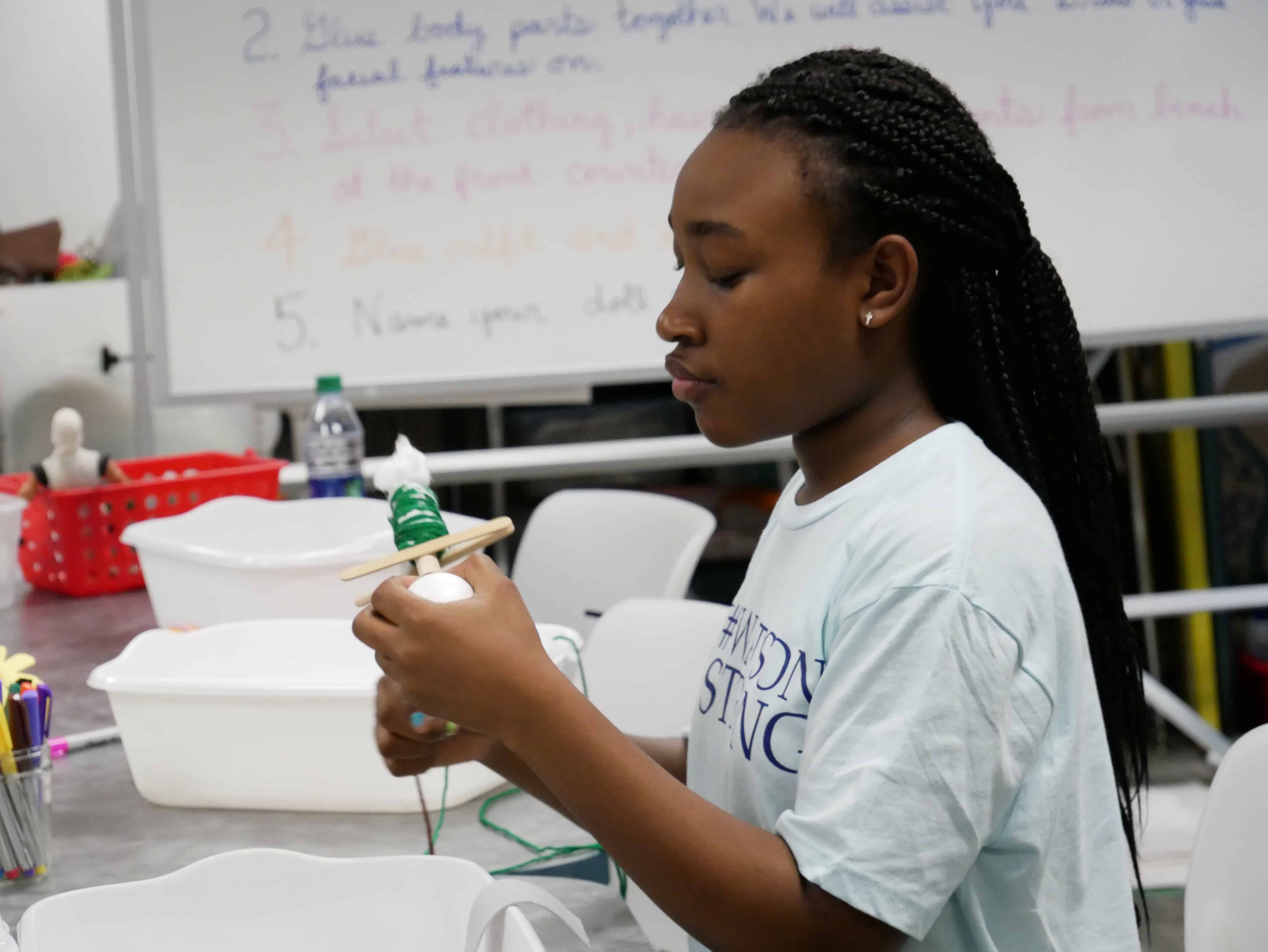

“Our students are outside of our traditional classroom a lot of the days of the year,” Winter says. It’s common to find middle school students exploring the campus library or in the 3D print shop. “These are students just like any other students on our campus,” Winter says. “Of course they look different, act different.”

The most obvious synergy, of course, is the use of university faculty in the classroom—a key element of the lab school concept, and part of the legislature’s requirements for its implementation.

Hands-on opportunities to be in the classroom with at-risk students are embedded in all of the lab school programs. At the Catamount School, more than a hundred Western Carolina University pre-service candidates have had clinical placements in just a year and a half, including every one of the university’s middle grades teacher candidates.

“They really work with the students and see these things happening live and in the moment,” Winter says. “We worked really hard to fully embed and have a relationship that flows both ways in terms of faculty and staff. We really like to highlight that we’re working hard to do that and do it well. Not just demonstration lessons but actually teaching in the middle school classroom.”

Earlier this school year, a UNC Greensboro professor, who is known for her expertise in literacy and had volunteered to teach at the Moss Street school, noticed that one of her elementary students was a non-reader and wasn’t interested in books. The professor ordered boxes of high-interest books for her students—featuring characters and storylines with which these students could identify. Many of them had never experienced the feeling of seeing someone who looks like them in a book, and they fell in love with the stories.

The little boy who didn’t want anything to do with books has experienced a dramatic change. “He has read every book in there,” O’Connor says. And this student was so excited for a new shipment of books for his classroom that he climbed inside the cardboard box. For the first time, his father said, the boy asked to go to the public library to check out books. “Successes that can’t be measured by test scores are things like asking to go to the public library for the first time,” O’Connor says.

One of the significant policy questions for lab school proponents, critics, and those tasked with running the programs is how to measure and report success.

As is the case in traditional and charter schools across North Carolina, test scores only tell part of the story. “It’s so much more than that,” says Penfield, the UNCG dean. “So many things come first.” While test scores are an important indicator of performance, administrators say, numbers often don’t reflect the nuances of a particular community. “Context really matters,” O’Connor says. “You can’t say one size fits all.”

There are institutional challenges, too.

Because the Catamount School’s class sizes are small, often below the 30-student-cohort threshold for inclusion in a North Carolina Department of Public Instruction report card. “Our picture will never fully be shared,” Winter says. “And that’s a problem.”

For example, the state doesn’t include the completion of ninth grade earth and environment science on its middle school report card. So even though the Catamount School believes that strategy is working—and other schools in the region are already trying it with their students—the success isn’t immediately apparent among Catamount School’s performance data. “That picture is never painted for anyone to see—except us when we sing the praises of the school,” Winter says.

Test scores also don’t reflect the challenges that many of the at-risk students who attend lab schools experience. “As you can imagine, because we are a middle school, we have students who come to us sometimes with years upon years of failure in school,” Winter says. “So there’s a lot of trauma and other kinds of issues that really do affect students.” That makes it harder to achieve progress.

“We made more progress academically in terms of growth last year than we expected to,” she says. “It’s not that we have low expectations for our students; we have high expectations. We just expected it to take longer for that needle to move.”

One sixth grade student had been to five different schools and was years behind grade level. The Catamount School was his first opportunity for educational stability—but his teachers had to address years of trauma.

“We’ve got kids that are more comfortable and confident coming to school regardless of their academic performance. We see that, and their families see that, as progress,” says Cody, the school’s principal. “With these students and the trauma that they’ve experienced, sometimes success looks like them coming to school day after day.”

The state’s pioneering lab schools have created road maps that leaders hope will be instructive for the programs that will open over the coming years.

But doing so wasn’t always easy.

“It’s been an adjustment having a university run an elementary school,” O’Connor says of the partnership between UNCG and Rockingham County. “That’s not something universities typically do.”

The needs of a 6-year-old elementary school student are quite different from a 21-year-old college student. “The elementary world operates at a different pace and a different scale than the higher ed world,” she says.

There are tangible differences that lab schools have encountered: The university system and DPI have different data and reporting systems, different nomenclature, and different human resources and staffing policies.

“Not only did we open a school, we opened a school district,” ECU School of Education Dean Grant Hayes in a 2018 interview. “No matter if you have one school or 21 schools, the types of processes and reporting to the federal government and even the state government is the same. It’s a lot more than about teaching and academics with nutrition and facilities and transportation.”

Funding is also a lingering issue. Much of the operating budgets for lab schools comes from the host university—funding which otherwise would go to other university programming. UNCG Dean Penfield says the legislature still needs to create “a long-term, statewide, sustainable funding model.”

But perhaps one of the greatest challenges lab schools continue to encounter, supporters say, is the perception that they are undermining local school districts. “We’re not taking over a school,” Winter says. “We’re not setting out to say we are the choice. Our mission is to say we are a choice for an option for students in sixth, seventh, and eighth grade in Jackson County.” The Catamount School continues to work to educate the public about what it is—and what it isn’t.

“When we thought about building a school, we did not set out to be a turnaround school,” she says. “We did not set out to create an environment in which we would be in competition with other schools in our area. We do not believe that is the intent of this legislation, nor is that our mission and vision.”

Instead, Winter says, the goal was to create an innovative environment where students who have traditionally struggled can thrive.

“We have kids who, for the first time ever, want to come to school,” she says. “And these are kids who have been in school for six or seven years before coming to us.”