On an unusually warm Saturday just after New Year’s, more than 150 teachers from Charlotte-area schools packed into a classroom on the UNC Charlotte campus. The room was at capacity.

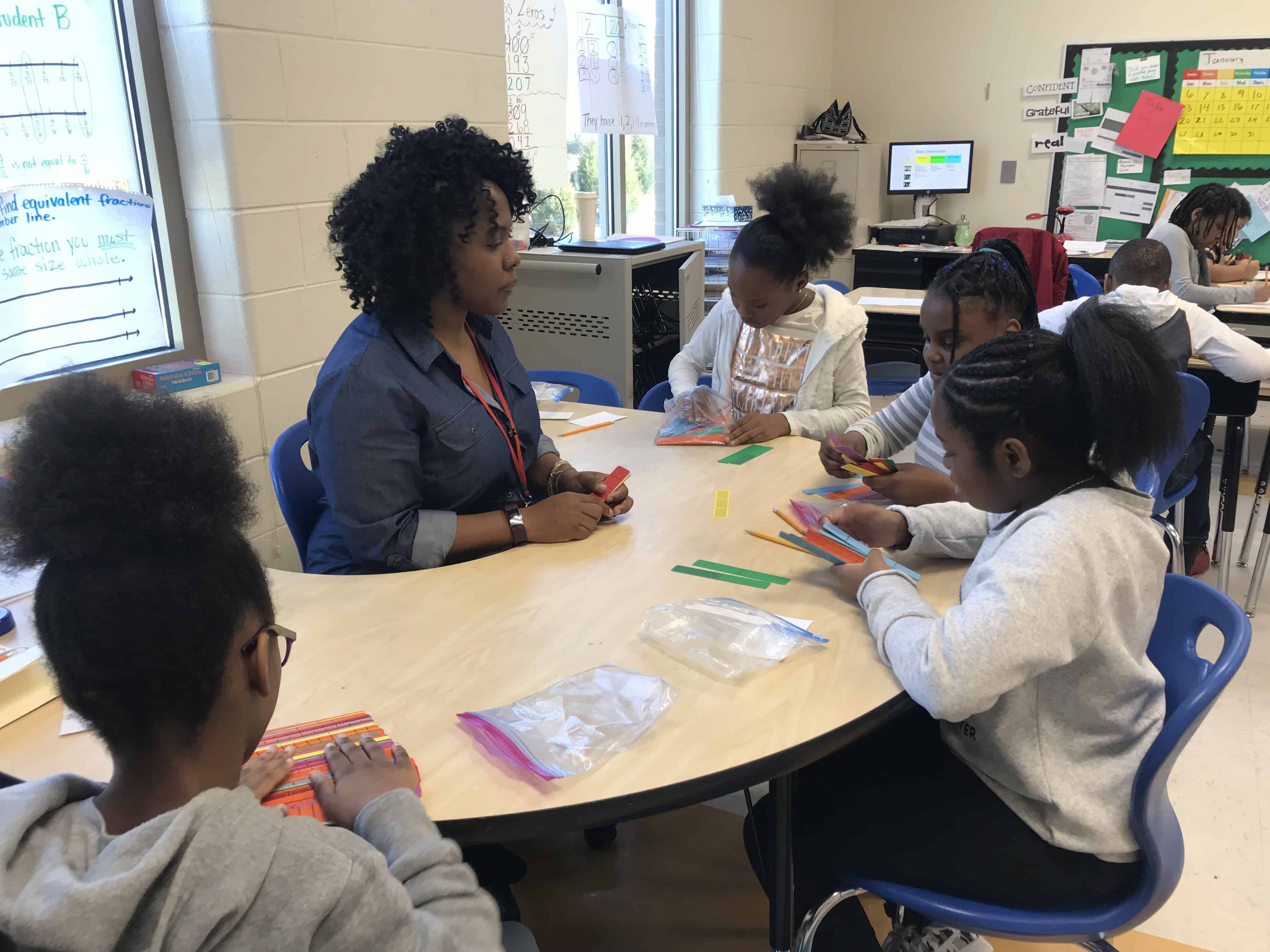

These experienced teachers had agreed to serve as clinical educators — coaches, mentors and, yes, supervisors for college students preparing to enter the teaching profession. But this was the first time UNC Charlotte has pulled together a large group of clinical educators for a training session and to emphasize the importance of their role in preparing the next wave of teachers for North Carolina’s classrooms.

“We want to make sure clinical educators are not just strong teachers but that they’re advocates for the teaching profession, that they’re positive members of the school community, that they’re leaders in the school community,” says Tisha Greene, the assistant dean for school and community partnerships at UNC Charlotte’s College of Education.

At the training session, Greene told the teachers how they should interact with their student teachers: “Not a colleague,” one slide read. “Mentor is a better word.” She walked the clinical educators through a presentation that included details about the student teaching experience: the schedule, roles and responsibilities, and the small honorarium that the clinical educators would receive at the end of the school year. She told them why the work matters.

“It matters to kids,” she says in an interview a few weeks later. “We have to have quality teachers because we want good education for our students.”

Clinical practice — the hands-on, real-life experience in a classroom during an educator preparation program — is critical to a teacher’s success and, consequently, essential to effectively educating the students in his or her classroom. But the term is still unfamiliar to many policymakers, and the concepts behind it are applied haphazardly across the country. As states evolve their perspectives on teacher training, universities and school districts have begun to hone their approaches toward clinical practice partnerships. The outcomes of these changes could amount to radical shifts in how lawmakers, administrators, academics and educators view teacher preparation. Or they could fall short.

In North Carolina and across the nation, the pivot toward a greater focus on clinical practice has occurred against a backdrop of a teacher pipeline squeeze.

Greene, who came to UNC Charlotte last summer after a career as a teacher and administrator in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, says the shortage of teachers makes it even more essential to effectively prepare teacher candidates for their careers.

“We have to have succession planning for our teachers,” she says. “There is a critical need in North Carolina for teachers, and if we don’t get it right in preparing future teachers, we won’t have any.”

Greene spent nine years as an elementary school principal, most recently at Oakhurst STEAM Academy, a partial magnet and Title I campus on Charlotte’s east side. “When I first started as a principal, there was no issue finding elementary school teachers. I could take my time hiring. I had the pick of the litter,” she says. “The last couple of years, if I didn’t snatch a teacher up immediately, I mean they often had three or four offers out before they even came in for the interview.”

While some of the first-year teachers Greene hired were well-prepared for the demands of the job, others, she discovered, were not. In many cases, these students came out of student teaching environments that Greene believes could have been stronger. Particularly, she says, if student teachers are placed in classrooms that do not reflect the students or teaching conditions they will encounter in the real world.

“Our students have to be placed in schools that mirror what their employment opportunities look like,” she says. “Otherwise they’re not equipped with the skills necessary to be successful in their first year as a teacher.”

Getting clinical practice right is especially important in North Carolina, where teachers with less than five years of experience make up roughly a quarter of the total teaching workforce. Beginning teachers are also disproportionately hired into high poverty schools, meaning their classrooms are more often populated by students of color.

“So there are some equity issues, certainly,” says Kevin Bastian, a senior researcher and associate professor of public policy at UNC Chapel Hill. It is in the interests of school districts, then, to do everything possible to prepare their incoming teachers for the environments they will encounter upon being hired.

That’s where strong clinical practice experiences come in.

“There needs to be a mindset around this as an apprenticeship,” says Bastian, who is the assistant director of the Education Policy Initiative at Carolina (EPIC) and is an expert on teacher preparation. “It’s the most hands-on and practical experience a candidate is going to have in a preparation program.”

“It’s right there at the end. It lets teacher candidates get a better sense of what this is actually going to be like,” he says. “It gives K-12 schools and principals and districts a sense of how effective those candidates might be. It could be like a year-long job interview.”

National experts agree.

“Clinical practice and partnership are central to high-quality teacher preparation,” says a 2018 report from the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education.

More than two years of work by the Southern Regional Education Board’s (SREB) Teacher Preparation Commission culminated last December in the call for more practice-based preparation for teachers.

“Research suggests that intensive methods instruction and high quality clinical experiences have an outsized impact,” the group’s report says. “The need to provide teachers with high-quality clinical practice is the clearest implication of the research on teacher preparation.”

The Commission recommends clinical experiences for all teacher candidates who are placed “with strong, experienced mentor-teachers.” The report suggests possible criteria to consider but is not prescriptive.

Importantly, the SREB recommendations do make it clear that not all clinical experiences are equal. “The schools where prospective teachers develop their skills are enormously influential,” the report says, “as are the mentor teachers who work with them and curriculum resources available to students in their classrooms.”

That message underscores a central challenge in the evolution of clinical practice: Educator preparation programs need to place their student teachers in a classroom, but school districts hold the institutional power to determine where those students are placed and with whom.

“There’s a certain sense that it is a bit of a mad dash and a scramble for educator preparation programs to get placements for all of their candidates,” Bastian says.

In North Carolina, clinical educators are required to have at least three years of teaching experience and be rated, at minimum, as “proficient” as part of the state’s Teacher Evaluation System, with preference given to teachers who are rated as “distinguished” or “accomplished.”

“The state criteria are extremely loose,” Greene says. “There are other things that we want, including leadership and coaching skills that aren’t explicitly mentioned in the State Board of Education policy.”

“North Carolina legislation and statutes pay more heed to that clinical teacher being an effective teacher but isn’t so explicit around their mentoring or coaching ability, and any training that’s going to go along with that,” Bastian explains. “Some of our research and others’ nationally shows the value of clinical educators who are both effective teachers—so they’re modeling good teaching practices—and clinical educators who are effective coaches or mentors who can actually help promote adult learning for a 21-year-old.”

Additionally, rural communities and those far from an educator preparation program are disadvantaged because their access to teacher candidates is limited by geography; EPPs are likely to place teacher candidates in nearby districts.

“That might mean that [rural districts] don’t quite have that same access to a potential labor source,” Bastian says.

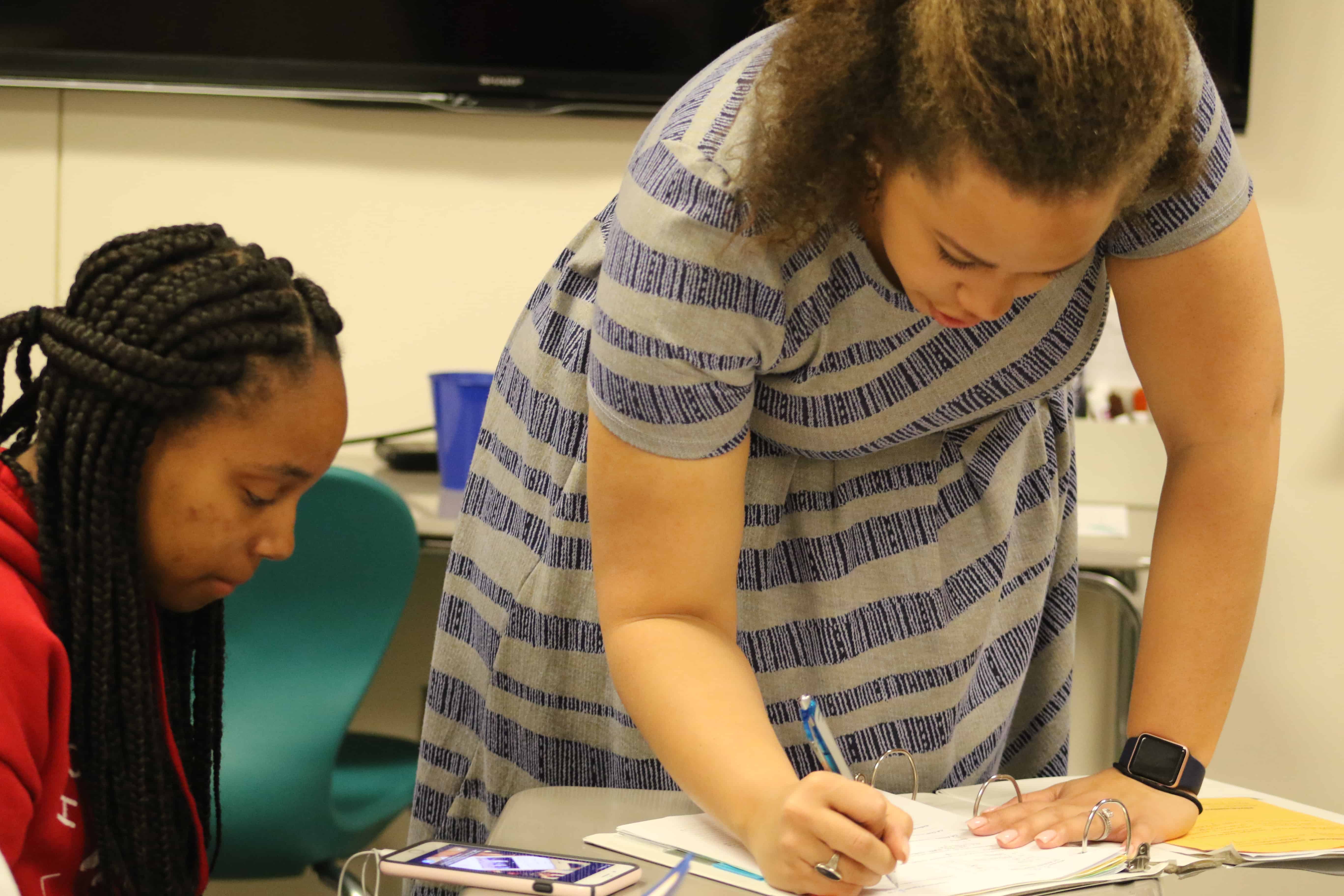

When Christina Spears reached the final semester of her master’s degree program at Meredith College in the spring of 2015, she began a full-time internship at a Wake County public school.

Her coordinating teacher, Veronique Lewis, was an experienced special education teacher. “She was there to support me, answer my questions, provide positive reinforcement and critical feedback,” Spears says. “I watched her mentor young men and women in a meaningful way.”

Being in the classroom — and in charge — full-time for an entire semester was the most valuable part of Spears’ internship experience.

She says she had a large support group, including fellow student teachers, the staff at her internship school, the Beginning Teacher Support Program, and Meredith faculty.

“I had a supervising professor who visited my classroom every week or two to observe me and check-in providing reinforcement and feedback,” Spears says. “She would check in on the progress of my final portfolio and speak with my coordinating teacher about the progress of my classroom practice and pedagogy.”

Kristofer Graham, a seventh grade social studies teacher at North Garner Middle School in Wake County, had a similar experience while finishing his degree at NC A&T State University.

His program required in-school experience each semester, crescendoing with a final semester of student teaching. “No two experiences were the same for me as I was able to work in elementary, middle, and high schools,” he says. Paired with an experienced history teacher, Graham was especially grateful for the way student teaching empowered him to create lesson plans. “It made sure that I had a solid plan every day that I entered the classroom,” he says.

Not all prospective teachers are so lucky.

Greene, the former elementary school principal, says student teachers sometimes get placed with less effective teachers, as either an intentional tool to boost test scores or because the school district couldn’t find enough clinical educators among their top teachers.

“It is critical that when a clinical educator is selected, they see that as a job opportunity and a growth opportunity for them and also as a recruitment strategy for the school,” she says.

The other challenge that both student teachers and clinical educators say they feel acutely is a lack of funding.

“It is near impossible to work enough hours in a week to earn a living wage while student teaching,” Spears says. “Student teachers work just as many, if not more, hours than classroom teachers if coursework were factored in. I also think paying student teachers or providing some sort of stipend might attract more graduates to education as a profession, particularly graduates of color.”

Greene says there needs to be a shift in societal thinking about teacher training. It should be analogous to internship and residency programs in other fields such as law or medicine.

“Almost every other profession, interns are able to fund their internship,” she says. “It bothers me that there’s very little funding out there to support our students during their student teaching internship. If they really want to be successful and take it seriously, we’ve got to find funding for them.”

Similarly, educator prep programs have an interest in finding funding for clinical educators and their professional development. “We’re trying really hard to invest more training and, frankly, pay for our clinical educators in hopes that our principals and our school partners will understand that this is a recruitment strategy for schools,” Greene says. “It is extra work for them. Unfortunately, sometimes our state doesn’t acknowledge that.”

Beyond funding, though, school districts and EPPs in North Carolina are thinking differently about their approach to clinical practice.

UNC Charlotte is currently redesigning its educator preparation program, planning to roll out changes in the fall. “What we are currently doing and what we will be doing are two different things,” Greene says.

The college is working to identify eight to 10 partner schools and strong clinical educators on those campuses. A University support liaison will be stationed at each partner school to provide support for both the clinical educators and the student teachers, as well as a link back to the others in the program. All will receive enhanced training, coaching and professional development.

“That way there’s depth and not breadth so we’re not spreading ourselves too thin,” Greene says. “We’re hoping that model will really be a better model than what we have now, which is just our students and our supervisors spread out everywhere.”

Across the UNC System, a network of nine lab schools, created by the General Assembly, is intended to serve the dual purposes of turning around low-performing schools and providing a space for enhanced educator preparation.

“The establishment of the UNC laboratory schools provides the opportunity to redefine and strengthen university partnerships with public schools, improve student outcomes, and provide high quality teacher and principal training,” the UNC System says. The lab schools connect with local school districts and intend to offer “real-world experience to the next generation of teachers and principals.”

Today, lab schools are in operation across the state with collaborations between East Carolina University and Pitt County Schools, Western Carolina University and Jackson County Public Schools, Appalachian State University and Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools, UNC Greensboro and Rockingham County Schools, and UNC Wilmington and New Hanover County Schools. Other programs are set to come on line in the coming years.

Much of the shift in North Carolina’s approach to teacher preparation and clinical practice was prompted by SB599, a bill passed by the General Assembly in 2017 that overhauled how the state was to govern teacher training. The law established the Professional Educator Preparation & Standards Commission, a body that makes recommendations to the State Board of Education on issues related to teacher preparation, licensure, and professional development.

One of the most significant changes from SB599 was the elimination of the “lateral entry” method of licensure, which enabled career-changers to enter the teaching profession in North Carolina without going through a traditional degree program. In its place, the legislature created what’s called the “residency model.” This pathway provides a one-year teaching license, renewable twice, and it requires affiliation with an EPP degree program. The bill says that teaching internships must last at least 16 weeks and residencies must last at least a year, but it specifies little about the components of those programs, nor does it provide funding for stipends.

Residencies are an emerging trend among school districts intent on addressing their teacher pipeline challenges—from recruitment to preparation and training to retention—while establishing strong partnerships with colleges and universities. But the definition of a residency varies widely from state to state.

“Building on the medical residency model, teacher preparation programs provide residents with both the underlying theory of effective teaching and a year-long, in-school ‘residency’ in which they practice and hone their skills and knowledge alongside an effective teacher-mentor in a high-need classroom,” says the National Council on Teacher Residencies in its description for the best practice teacher residency.

The group says ideal residencies deeply blend theory and practice, making them “a unique route into teaching, helping participants draw meaningful connections between their daily classroom work and the latest in education theory and research.” Importantly, the NCTR calls for a stipend for living expenses for the duration of the residency and a subsidized master’s degree upon completion of the program.

The SREB, in its 2018 report on teacher preparation, also highlights the potential of residencies as a tool for recruitment and retention. “This grow-your-own approach to teacher training holds promise. Novices learn the specifics of the curriculum and student population as well as the approach to teaching in the school districts where they intend to work.”

It specifically calls out Louisiana’s Believe and Prepare program, which is a collaboration among local school systems and EPPs for year-long residencies. But the SREB acknowledges that funding is limited and is unlikely to be enough to fund residencies for all prospective teachers who are interested or all school districts that want to implement the programs. SREB recommends states direct funding for year-long residency stipends to “candidates who intend to teach in hard-to-staff schools.”

Much of the promise for residencies comes from the early success of the GO First STEP student teaching program in Atlanta. Fulton County Schools, which serves 98,000 students, reenvisioned the GO First STEP program last year as a year-long internship program. It will help the school district “build deeper relationships and connections with top talent earlier in their careers,” says Arthur Mills IV, the district’s executive director of talent management and organizational strategy.

Interns are typically senior education majors. They agree to student teach in Fulton County Schools for an entire school year, paired with what Mills calls a “high-performing and carefully selected experienced teacher.” The intern would earn a $3,000 stipend for meeting certain goals during the year and, after successfully completing the program and graduating, would be eligible for early, prioritized placement for a teaching job the following year.

“Simply challenging our team to reimagine Fulton’s student teaching strategy with some ‘outside the box’ thinking could ultimately address 20- to 25 percent of the district’s teacher vacancies each year with talented, mission-driven teachers already familiar with our students, schools, and communities,” Mills says. “We’ll also be building sustainable talent pipelines into many of our harder to staff schools.”

In North Carolina, opportunities abound for innovation in clinical practice.

“It’s not something that districts are particularly thoughtful about, in terms of human capital management strategy, in thinking about student teaching as an extended job interview,” says Bastian, the UNC researcher. “It’s a bit of an untapped possibility.”

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools was the first local education agency in the state to receive approval from the state to serve as an educator preparation program. CMS launched its teacher residency program last summer, enrolling 82 candidates in a six-week summertime training program designed to prepare mid-career professionals to become teachers. Those who finish the program are eligible to earn their teaching license within a year.

CMS has used the program, for which it charges participants $1,500, to specifically target teacher vacancies in elementary schools, middle- and high school math and science, and middle school English Language Arts. The early success of CMS’ program—participants aren’t guaranteed a job, but the district was able to fill dozens of hard-to-staff teaching vacancies this school year with residency participants—will likely prompt other school systems across the state to launch similar programs.

The evolution of clinical practice in North Carolina carries tremendous importance for the future of North Carolina’s teaching workforce and the students those teachers will serve.

Rather than approaching teacher training and hiring in separate silos, Bastian says enhanced collaboration among educator preparation programs, teaching candidates, school districts, and clinical educators is critical.

“It might be today’s problem for the EPP and the candidate to get a placement, but it soon becomes tomorrow’s problem for the districts because they’re soon going to be hiring those individuals,” he says. “A shared recognition of not just the challenges but the opportunities in a collaborative environment is a mindset that needs to be changing.”

And although there are big moves the state and school districts could do—providing true stipends for year-long residencies, for example—Bastian believes much of the innovation can happen by thinking differently, more creatively, about the possibilities.

“Getting clinical placements right and being intentional and strategic about it is one of those things that’s a little bit more about making the trains run on time,” he says. “It’s more of using data, leveraging partnerships. It’s a bit of an untapped possibility.”

This is Part One in a series on clinical practice in North Carolina. In Parts Two, Three, and Four, we will profile three different educator preparation programs and the clinical practice experience of their students.

Correction: A previous edition of this post incorrectly spelled Tisha Greene’s last name in one instance. It has been updated.