It was a hot, humid Wednesday morning on a hill on the campus of Surry Community College in Dobson, N.C. Around me, 16 different varieties of grapes hung three weeks away from harvest to be turned into wine, pending one special ingredient — science.

“When we grow grapes on a hill, we have the benefit of cold air draining away from the vineyard, so vineyards tend to be located on hilltops,” said viticulture instructor Sarah Bowman. “Cold air sinks [and] warm air rises, so there’s just a couple degrees difference on the hilltop as compared to the valley floor. We use that topography to our advantage.”

According to Bowman, the hilltop also allows for better surface water drainage since grapes don’t require ample water. With the Yadkin Valley’s sandier soils, milder winters, longer growing season, and higher elevation, Surry Community College’s location happens to be on prime vineyard land. But the land is just one small piece of the science that goes into making wine that students learn in the college’s viticulture and enology curriculum.

“It’s my job to make sure students are exposed to a lot of the different challenges, but also the rewards of viticulture, and that when they leave the program that they are able to think critically and make decisions on their own,” Bowman said. “There really is no recipe for grape-growing.”

There is, however, one thing that can bring any vineyard down: pests and disease. Disease is one of the many challenges in the southeast, which is why Surry Community College includes an entire course on the subject.

“There are plans in the year or two to start experimenting with some recently released varieties that are disease-resistant, specifically for disease that we experience here called Pierce’s disease,” Bowman said. “It limits the types of varieties that you can grow regionally and that’s dependent on whether or not you have the insect vector that causes the disease.”

3 weeks away from harvest for these beauties @surrycc vineyards! You know you wanna taste! @NCCommColleges @Awake58NC @EducationNC #Awake58 pic.twitter.com/hLCh7iMFTp

— Yasmin Bendaas (@yasminbendaas) August 29, 2018

In addition to disease management, students gain hands-on experience in the vineyard learning about pruning (about 75 percent of the annual growth is removed at pruning), canopy management, crop yield estimation, nutrient management, and vineyard floor management.

“This is a whole system, so you’re managing not only the vines but the land and the soil and all the other organisms that live in here and have a habitat here,” Bowman said.

Later that evening students gathered for a course, not out on the vineyard, but in a lab at the college’s Viticulture and Enology Center.

Under the guidance of enology instructor David Bower, students peered into a refractometer to measure the amount of sugar in recently harvested grape juice. The amount of sugar matters because yeast turns those sugars into ethanol—resulting in wine’s alcohol content.

“There’s lots of chemistry. Lots of chemistry,” Bower said. “I think it’s a lot more than people expect, but it’s something we prepare you for. We have a grape and wine science class that kind of goes through the basic chemistry concepts, and then my introduction to wine-making class goes through basic [chemistry] concepts.”

Check out these beautiful NC wines made right here @surrycc ❤️ @Awake58NC @NCCommColleges @EducationNC #Awake58 pic.twitter.com/3d3PmlVziD

— Yasmin Bendaas (@yasminbendaas) August 29, 2018

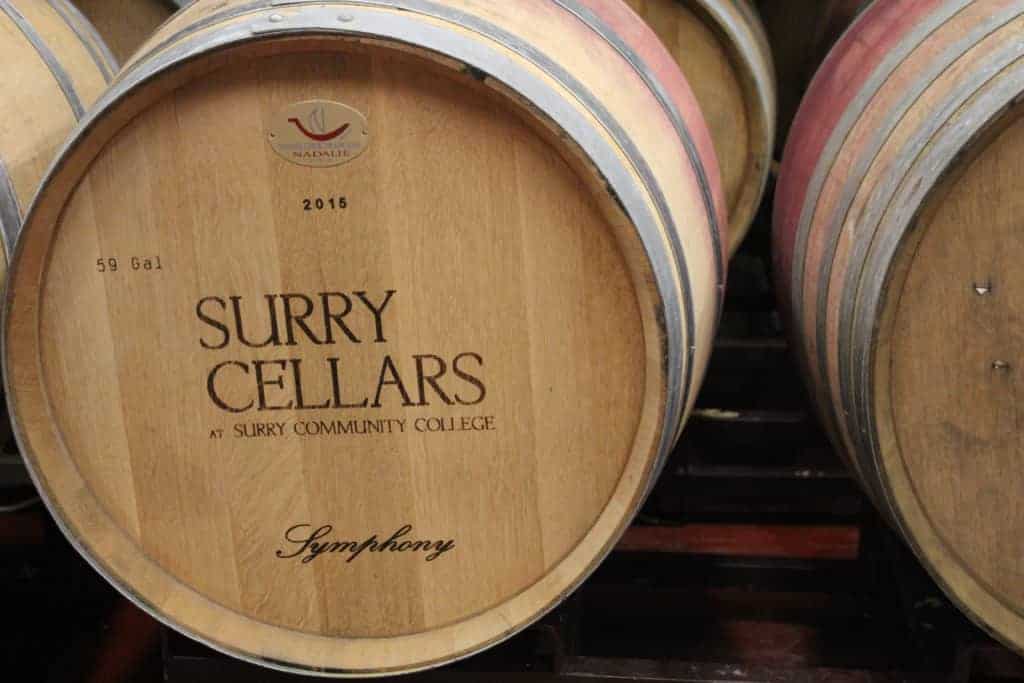

The lab sat adjacent to a fully-functioning winery—brimming with the scent of five simultaneous fermentations—where Surry Community College has scientifically cranked out several award-winning wines.

“We produce about 2,500 gallons of wine. That equates to about 800 to 1,200 cases of wine a year,” Bower said. “We have everything that you would have at normal winery.”

However, Bower said wine making is more of an applied science rather than any one field due to its incorporation of everything from microbiology to general and organic chemistry to environmental biology.

“The biggest thing is the interactions — how it all interplays,” Bower said. “Because each decision that you make makes a difference.”