Schools and districts are doing the best they can to support students despite severely limited school health personnel, according to presentations of the first meeting of the student health subcommittee of the House Select Committee on School Safety on Monday.

The Committee on School Safety first met on March 21 and divided into two working groups: one focused on student health, the other on student physical safety.

At the subcommittee meeting, experts offered presentations to show the efforts of schools and districts to improve student health despite resource limitations. Presenters stressed that creating a comprehensive, team-based approach among the various school health personnel is crucial to ensuring that students receive the mental health services they need.

Below is a table outlining details discussed about each of the four school health personnel during the meeting.

|

Title |

N.C. ratio |

Certification |

Responsibilities |

Salary |

|

School counselor |

vs. 1:250 |

Specialized master’s degree required Licensed from N.C. DPI |

Social-emotional health Cognitive (academic) well being Career/college readiness |

Paid on teacher salary scale at the master’s degree level |

|

School psychologist |

vs. 1:700 |

Completion of an approved program in school psychology at the sixth-year level 60+ graduate credits, supervised internship for 1200-1500 hours License for LEA employment issued through N.C. DPI |

Academic, behavioral and mental health supports Evaluation, assessment, and data analysis Consultation with teachers and families Crisis prevention and response Support diverse learners |

Not paid on a teacher salary scale $43,390 (starting) – $61,920 (25+ years) National median salary: $63,000 |

|

School social worker |

vs. 1:400 |

Minimum bachelor’s degree required Additional coursework for School Social Work licensure by N.C. DPI |

Address children’s unmet physical and emotional needs that interfere with school attendance Connect families to needed physical and mental health community resources Serve as liaison team member with other instructional support and school staff |

Paid on teacher salary scale at the bachelor’s degree level |

|

School nurse |

vs. 1:750 |

Specialty practice of a Registered Nurse (RN) with a bachelor’s degree and school nurse certification. Certified by American Nurses Credentialing Center or the National Board Certification of School Nurses |

Refer emotional or mental health concerns to other support personnel, such as counselors, while they address physical manifestations Provide care management services to students in need of long term support |

Paid on teacher salary scale at the master’s degree level |

School counselors

“School counselors are the front line of mental health issues in schools,” said Tim Hardin, president-elect of the North Carolina School Counselor Association.

Hardin opened Monday’s meeting by discussing the role of school counselors and why they are an important aspect of the mental health resources within a school.

Unlike school nurses or psychologists who may only see a small percentage of students who need specific services, school counselors are responsible for the social-emotional health and academic well being of every student in their school. They have the goal of ensuring each student graduates career or college ready.

While this situates school counselors in a unique position to recognize potential mental health issues before they become more serious, it also means that counselors are stretched across numerous responsibilities including academic course planning, holding small group sessions on suicide prevention, and offering one-on-one counseling to students in crisis.

“As a counselor, we may be doing a suicide assessment or threat assessment, and then looking at transcripts to make sure students are graduating college and career ready in the midst of all the other issues they’re dealing with,” said Vanessa Barnes, a school counselor at Millbrook High School in Wake County.

Rep. Donna McDowell White (R-Johnston) asked what percentage of the students in a counselor’s caseload they are actually able to meet with one-on-one.

“It is a balancing act. Teachers make referrals to us and we try to bring students in,” said Barnes. “We are working with them individually and in groups to make sure we aren’t missing anyone, but it’s hard with the numbers we have to make sure we’re meeting every need, every day.”

According to Hardin, the current ratio of students to school counselors across North Carolina is 1:386. Hardin requested that the committee consider at least one mandated full-time certified school counselor in every North Carolina public school and public charter school. This would move the statewide student to school counselor ratio closer to the recommended ratio of 1:250.

Hardin’s full presentation can be found here.

School psychologists

Heather Lynch Boling, president of the North Carolina School Psychologist Association, shared data, information, and anecdotes about the status and impact of school psychologists.

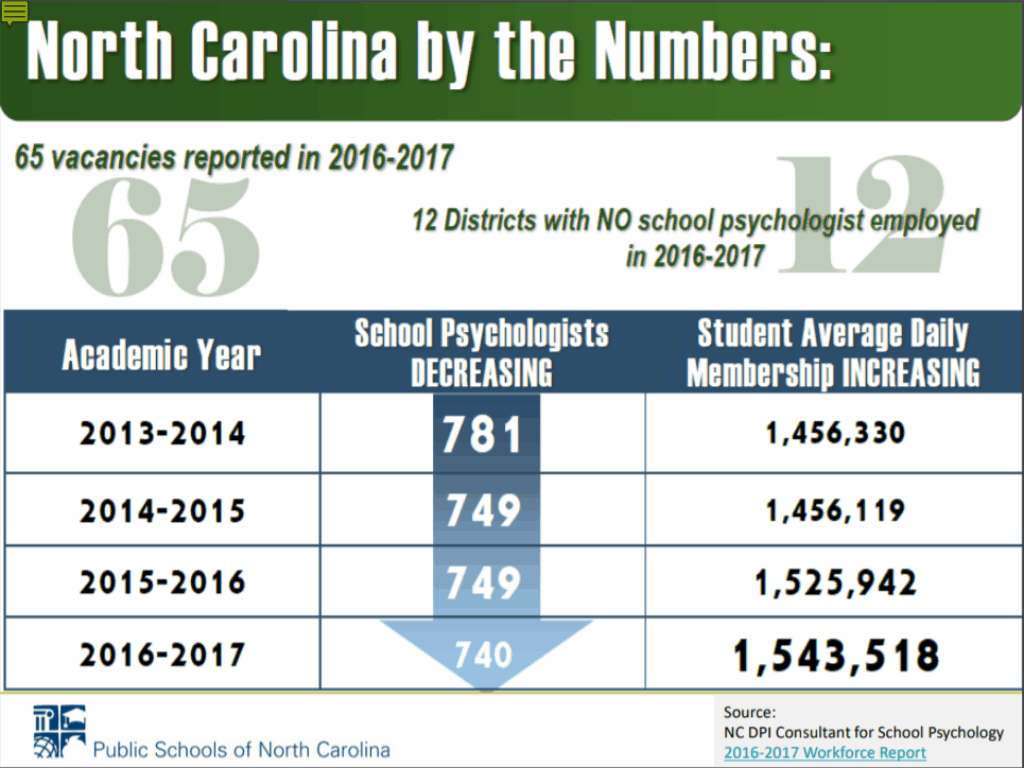

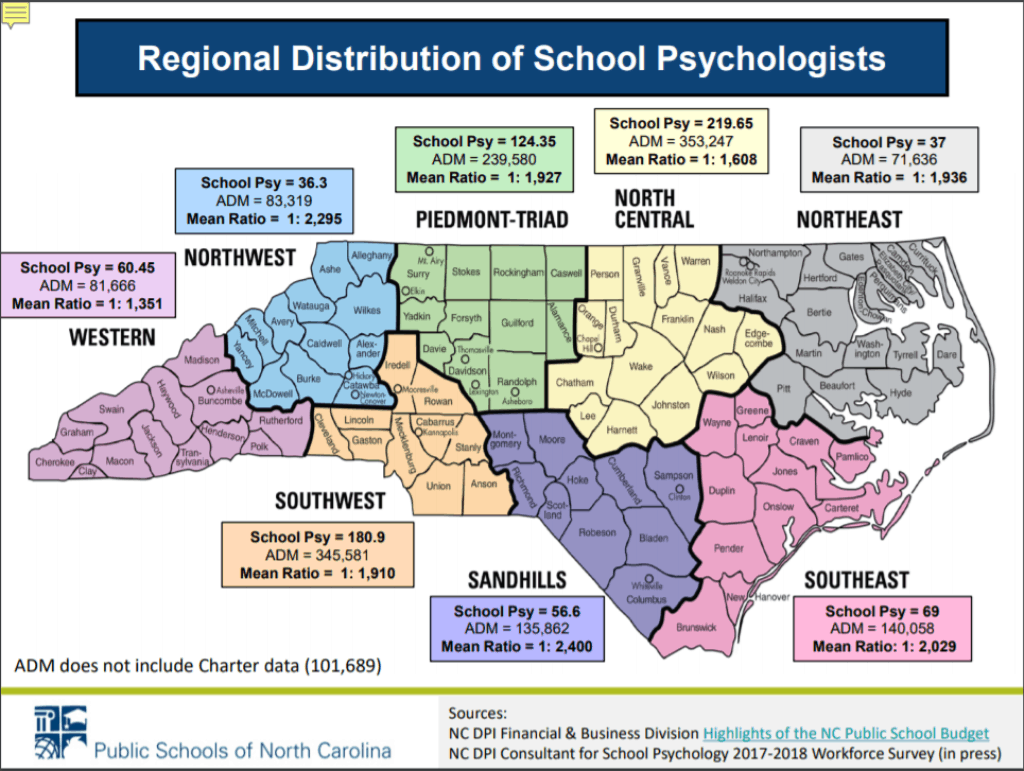

According to 2017-2018 NC DPI data, there is one school psychologist for every 2,083 students in North Carolina. The recommended ratio is one school psychologist for every 500 to 700 students. In 2016-2017, there were 65 school psychologist vacancies across the state and 12 school districts without any school psychologists. As of 2017-2018, there are 75 such vacancies.

“Currently, lots of our school psychologists don’t have an opportunity to provide comprehensive services due to ratios,” said Boling.

Boling outlined a day in the life of a school psychologist. In general, a traditional school psychologist spends their day assessing students for special education eligibility using a test kit. Often, one school psychologist will serve multiple schools or an entire district of schools, limiting their ability to develop a comprehensive support plan for a student they have only interacted with for a few hours during testing.

“Our children are more than black and white scores on a paper. We need to be able to talk to teachers, talk to their families, and do observations to get a really good look at our children, so that we can support comprehensive service delivery,” said Boling.

The North Carolina School Psychologist Association recommends increasing access to school-based mental health services, increasing pay for North Carolina school psychologists, and enacting reciprocity for North Carolina licensure to fill the gaps with qualified candidates.

“All means all. When we’re talking about our children, we need to be able to support our communities to make sure that all children get the right help at the right time by the right people,” said Boling. “I do believe that has to do with school safety and the direct need for school support personnel.”

An outline of Boling’s full presentation can be found here.

Lynn Makor, a consultant for school psychology at N.C. DPI, presented further information on school psychology licensure and practice.

According to Makor, there are five school psychology training programs in North Carolina and all of them are approved programs by the National Association of School Psychologists. Compared to the 1,271 active school psychology licenses in North Carolina, there are only 781.35 school psychologists employed in North Carolina schools.

“Closing that employment gap needs to be priority number one in addressing the vacancies that exist. Moving towards an improved staffing ratio would be the next target after that,” said Makor. “These five training programs are necessary but not sufficient to put a stop to the 75 vacancies in the state. We need to look to other states and have targeted recruitment efforts.”

According to Makor, having a streamlined licensure process and creating a more competitive salary schedule would incentivize candidates with a national credential to come to North Carolina.

Cynthia Floyd, a school counseling consultant at N.C. DPI, expanded on Makor’s remarks by outlining the roles of school social workers and school nurses.

“Part of the difference in ratios is that school counselors serve all students. If there are 450 students in a school, the school counselor serves every last one of them,” said Floyd. “They heavily rely on the school social workers, psychologists and nurses to identify additional needs.”

Makor and Floyd’s full presentation can be found here.

Improving mental health services in schools

Mark Benton, deputy secretary at the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), presented on the status of mental health issues and coverage across the state.

According to Benton, 10 percent of North Carolina’s population under age 18 struggle with a significant mental health or substance abuse issue, while 31 percent of those are not receiving the treatment or help they need.

N.C. DHHS recommendations included:

- Increasing the number of individuals trained under the Mental Health First Aid program

- Expanding the use of the Community Resilience Model by school personnel

- Expending Counseling on Access to Lethal Means

- Providing more training for clinicians through the CEnter for Child and Family Health

- Increasing the number of school counselors, psychologists, social workers and nurses

- Expanding the number of services a school district can bill Medicaid

- Amending state law to exempt school districts from collecting N.C. Health Choice co payments

Benton’s full presentation can be found here.

Kym Martin, executive director of the N.C. Center for Safer Schools, presented multiple examples of comprehensive school based mental health models.

Martin also identified threat assessments as a key instrument for keeping schools safer.

“Consider if we need to require that schools put a threat assessment process and instrument in place,” said Martin. “Many have them informally, but if we had legislation that required it and could provide them with tools that they could use and instruments with which they could do this, then I think we could go a long way.”

Martin’s full presentation can be found here, starting on slide 35.

Next steps

Chairman John Torbett (R-Gaston) requested that Martin aid the committee in the creation of two pieces of legislation: a statewide peer-to-peer program where high school upperclassmen mentor freshmen students and a requirement for a school threat assessment in every school.

Rep. Becky Carney (D-Mecklenburg) asked that the committee consider the compassionate schools model, and Rep. Donna McDowell White (R-Johnston) requested that the committee consider the statewide launch of the anonymous tip line phone application called SPKUP NC.

The subcommittee on student health meets again on April 23. The subcommittee on student physical safety and security will hold their first meeting on April 17, followed by a second meeting on May 3.

The full state House Select Committee on School Safety will meet again on May 10 to consider recommendations from each of the subcommittees ahead of the short session.

Recommended reading