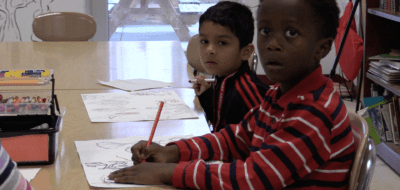

Emily Alejo, 9, had a choice to make. Her school, Haw River Elementary in Alamance County, was offering students after-school clubs once a week. Would she choose volleyball, music, yoga, newspaper, Harry Potter crafts or something else? Her friends wanted to try robotics, so she tagged along.

Within weeks, she learned how to run a motor and construct a toy car, bird, and crocodile. Robotics came easily to her, so she began helping others in her club and teaching her 2-year-old sister the basics.

“I heard that boys were better at robotics because it’s more of a boy thing, but I don’t think that’s true,” Emily said, working on her latest robotics project with friends.

Emily and her classmates are part of a statewide experiment known as Restart. The program allows some of North Carolina’s lowest-performing schools to have more flexibility like charter schools.

They can try new things to improve student performance, such as extending school days, using money in ways not designated by the state, and hiring teachers for positions other than those for which they are licensed.

Haw River Elementary School decided to add after-school clubs, eliminate some teacher assistant positions, add more teachers, and reduce class sizes. They also added a school support coach to help teachers improve their lesson plans and use more data to track students’ progress.

Haw River was one of the first schools in the state approved for the Restart program in the spring of 2016, along with four others:

- Barwell Road Elementary (Wake County)

- Walnut Creek Elementary (Wake County)

- E.M. Rollins Elementary (Vance County)

- Goldsboro High School (Wayne County)

Since then, the program has expanded rapidly. Every month, more schools come before the State Board of Education to request Restart status by providing plans of the changes they would like to make. Currently, 103 schools in the state have been granted permission to use Restart, and more are waiting for Board approval.

Since Restart began, there has been some confusion about the program, particularly about the involvement of the state’s Department of Public Instruction.

“When it first started, we got a few phone calls that were, ‘OK, so our application got approved. Now what do we do?’” said Nancy Barbour, director of educator support services for the state Department of Public Instruction. “And it was like, ‘You implement your plan. There you go. That’s what you do.’ The schools may have thought that they were applying and that now the state was going to come in and do something, (but) it was never intended that way.”

The school autonomy is by design. The Restart program relies on the premise that schools know what is best for their students and should be granted flexibility to make changes. The principles of the model are similar to those that govern charter schools.

Alamance-Burlington School System Superintendent Bill Harrison was interested in trying after-school clubs at Haw River Elementary. The logistics of setting up clubs for more than 500 students has been challenging at times, but Harrison and Principal Jennifer Reed have been happy with the program.

“We just feel our kids need to be with us more. Too many of them, the experiences they have outside of school aren’t as positive as what we wish,” Harrison said. “My kids were able to go to the Y[MCA]. My kids were able to go to dance…Too many of our children here don’t have those opportunities.”

The goal is to change students’ attitudes toward school and hopefully improve their academics.

“We wanted to keep the students at the center of our attention and figure out what could really motivate and drive them,” Reed said. “Kids are excited. They’re motivated. It’ll be interesting for the end-of-the-year data to see how that goes and to go back and see what club they were involved in.”

Reed said she has fielded emails from other principals who want to know how the Restart program works. Her advice? Have a superintendent who is supportive, visit schools that are doing the program, and build a model that meets your school’s needs and does not simply replicate others’ programs.

The varieties of Restart

In the 2016-2017 school year, North Carolina had 505 low-performing schools and 468 recurring low-performing schools, or schools that were low performing for at least two of the past three years. The Restart statute says any of those 468 schools may apply for the charter school-like flexibility the program allows. But that means different things to different people.

“If they wanted to be a Restart, it’s not a model,” said Joe Ableidinger, chief program officer and director of innovation for The Innovation Project, a group of district superintendents, staff, and collaborators working on education innovation in North Carolina.

He said there is no rubric for what happens once a school chooses to become a Restart school. There are no specific changes that need to be made. It is even possible that a school could choose the program and then do nothing with it at all.

That is what happened with Siler City Elementary School in Chatham County. The school applied for the Restart program in 2016 and was approved but has not made the changes it had initially planned. Instead, the school is planning to work with North Carolina State University’s Caldwell Fellows to host a summer school program for its students, according to Principal Larry Savage.

“We applied for licensure waivers under the [Restart] program, and to date, we have not needed the waivers. We have been able to find fully licensed teachers to staff our classrooms. We also applied for flexibility related to calendars and instructional time, and we also haven’t needed that, but we continue to explore options,” Savage said. “Having said that, as a principal, we really appreciate the flexibility and recognition of the challenges we face at the state level.”

Siler City Elementary has shown improvement, even without the planned Restart changes.

“Last year, we didn’t need that flexibility, but we did do great things,” Savage said. “Last year was a fantastic year. We actually exited that status as being designated as ‘low-performing,’ and we’re proud of that. Our school grade has risen to a C, and we exceeded growth last year…teacher turnover rate, suspensions [are] below state average. We’re proud of all that, but we’ve gotta sustain it.”

In Edgecombe County, the district uses Restart schools as a buttress for a pre-existing program: Opportunity Culture, which focuses on teacher leaders, multi-classroom teachers, and teacher-led training. The goal of the program is to extend the influence of good teachers to reach more students.

The county has four schools approved for Restart: North Edgecombe High School, Phillips Middle, Coker-Wimberly Elementary and Princeville Elementary, though Princeville’s plans were delayed by Hurricane Matthew in October 2016.

Edgecombe County’s leadership spent time considering what it wanted to do at the four struggling schools, according to Erin Swanson, director of innovation for the school system.

“We had a plan in mind,” she said. “We knew we had to do something dramatically different there.”

Opportunity Culture was the dramatic intervention the district chose. But when district leaders heard about Restart, they saw it as a way to expand the impact of the Opportunity Culture project. Flexibility around licensure and class size, as well as financial flexibility, sounded appealing.

Restart schools do not have to adhere to class size laws, which have been a long-running source of controversy in North Carolina. The General Assembly mandated class size restrictions in 2016, and districts have asked for relief ever since. Earlier this year, legislators voted to phase-in the requirements and provide more funding for enhancement teachers (arts, music, physical education) — something many schools said they would have to lose in order to accommodate smaller class sizes.

“All of these things we knew would help us as we were trying to implement Opportunity Culture,” Swanson said.

So far, Edgecombe County has primarily used financial flexibility and a little bit of the licensure flexibility — hiring teachers for subjects other than those in which they hold licenses. District leaders are trying to take careful, measured steps as they make changes.

For instance, the district found some interest from parents in extending the school day and year for schools with Restart status. But last year, Coker-Wimberly and Princeville were the only schools with Restart status; the other two did not come on board until this fall. Because there is a feeder pattern of students from elementary to middle to high school, district leaders believed changing the school day or calendar would have been disruptive.

“We wanted to be sure first that the foundations during the school day were in place first,” said Valerie Bridges, superintendent of Edgecombe County Schools.

Those foundations include having capable teachers in every classroom before launching more extensive changes.

Barwell Road Elementary School in Wake County is one school that decided to take calendar changes and run with them. The school began as a Restart last year — it was one of the first five to be approved — and calendar flexibility was one of the initial changes district leaders hoped to implement.

“It helped because, right off the bat, that’s one of the things that we were allowed to do; that you could change your schedule,” said Assistant Superintendent James Overman.

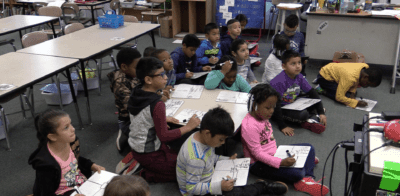

The district wanted to extend learning in classrooms beyond preparing students for standardized testing. At both Barwell and Walnut Creek Elementary School — another Restart in southeast Raleigh — the district added 10 days to the school year for learning symposiums. The symposiums focus on creative learning opportunities schools would not typically have time for during the school year.

For instance, fourth-graders created a movie theater experience, complete with a concession stand. The first grade transformed into a camp where students “kayaked” and “canoed” down the hall.

“Part of the reason that we chose to add (learning symposiums) came from the idea of summer school or summer camp, but you didn’t get to give everybody that experience,” said Beth Hodge, senior director for innovative and strategic initiatives for the Wake County Public School System.

Barwell Road also extended the school day so it could offer clubs after school on Thursdays and pay teachers to work with the students during clubs.

Michael Dunsmore, superintendent of Wayne County Schools, was part of the group of superintendents that initially worked with The Innovation Project (TIP) to jumpstart the Restart program in North Carolina. He was particularly interested in using the program with Goldsboro High School, which was once high-performing but has since struggled.

“Everybody was tired of seeing this school slip backwards, and we were looking at ways within the General Assembly and the state statutes of how we could help this school and return it to its glory days,” he said.

More than half of the school’s staff was replaced after the implementation of Restart at Goldsboro High, one of the first five schools approved for the program. Calendar flexibility was a big driver in the decision to choose the program, but so was licensure flexibility.

Goldsboro High School is in close proximity to Seymour Johnson Air Force Base so there were a number of military families that included teachers who had come from other states. There were also a number of military personnel and their family members with expertise that they were willing to share with the high school students.

But the requirements of licensure were onerous for the highly-mobile military population, and Goldsboro High was not able to hire the experienced people they had working right next door.

“I think a lot of folks in the community, particularly the students, didn’t realize what was going on over the fence at Seymour Johnson,” Dunsmore said.

Hitting the brakes on Restart

While some school districts quickly embraced Restart, others took a slower, more cautious approach.

In July 2016, the State Board of Education approved 14 Durham schools for the Restart program. A year and a half later, the district reversed course and asked the state to remove 12 of the schools from the list.

Durham Public Schools Superintendent Pascal Mubenga, who began in the role in October, explained the drastic change in a letter to the state education department in December. With the projected costs of the state’s planned K-3 class-size reduction and its possible financial impact on the district’s budget, Mubenga decided it would not be fiscally wise to simultaneously launch a new program in 14 schools.

Nakia Hardy, Durham schools’ deputy superintendent for academic services, said the district decided to keep two of the 14 schools in the Restart program: Glenn Elementary School and Lakewood Elementary School.

“When you look at Restart across the state, many districts began with two to four schools, and 14 schools was very ambitious to begin,” Hardy said.

Part of the reason Durham decided to keep the two elementary schools enrolled in the Restart program, according to Hardy, is that it prevents the state from trying to enroll them in a separate program for struggling schools called the Innovative School District, or ISD.

“It was part of the decision,” Hardy said. “We also looked at the data and talked with the principals, so that we could make a very thoughtful recommendation.”

Glenn and Lakewood were considered last year for the ISD, a new state program that chooses five struggling schools from across the state and hands them over to management organizations to try to improve their performance.

When the ISD expressed interest in Glenn and Lakewood last year, Durham school and community leaders fought the proposal. By law, the ISD can no longer consider Glenn and Lakewood schools since they are part of the Restart program.

For now, Durham is in the beginning stages of Restart and has not yet determined how the program might be implemented. The district needs time, Hardy explained, to talk with the principals before announcing what changes will be made. They are considering what flexibility they might want with instruction, curriculum, and scheduling.

Even in schools where the Restart program is taking place, not everybody is enthusiastic about the model.

Jim Merrill, former superintendent of Wake County Schools and chair of the first board of superintendents for The Innovation Project (TIP), said that change can be difficult.

“It’s hard for folks when all of a sudden you say, ‘OK, you’re free,’” he said.

It requires creativity to implement Restart, and a willingness to let go of the past, he said.

“My own organization has its own structures and traditions that I have to sweep away,” he said.

But the wariness about Restart can go deeper for teachers than just having to change how they instruct students. Sometimes becoming a Restart school means eliminating staff.

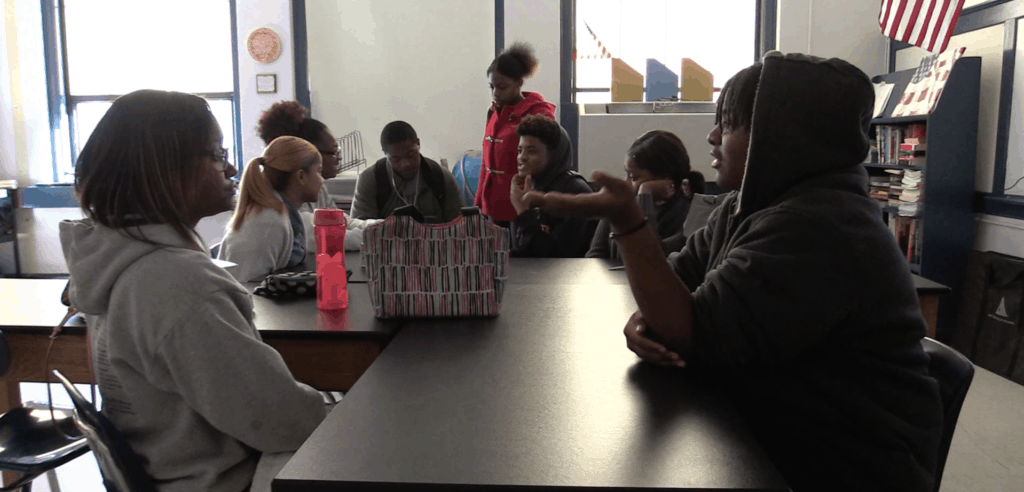

Paula Wilkins, principal of Cook Literacy Model School in Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools, understands the staffing challenges of Restart. Cook was previously identified as a “priority school,” meaning it was one of the lowest performing Title I schools in the state.

Staff changes were a difficult part of the Restart process for teachers at Cook, Wilkins said. When they were told the school was adopting the Restart model, they learned the school had decided to make staff members reapply for their jobs.

“For people at that time…it was kind of the slap in the face of, ‘We’ve been here and now you’re telling me I have to reapply to my job,’” Wilkins said.

Worse still, families in the community learned the school was becoming a Restart by hearing about what was happening to teachers.

“They started these series of meetings, which did not go very well,” Wilkins said.

Community members were confused as to why the program was necessary and why their children’s teachers were being asked to reapply.

Wilkins came on board as principal shortly after the meetings, and immediately began trying to reach out to the community. She had a series of get-togethers with families and made an effort to get them involved in the school’s design team.

“There was just a long period of distrust,” Wilkins said.

But Cook weathered the transition. The school has remodeled itself around reading, offering a longer school year, additional classroom hours, and other strategies focused around improving reading proficiency.

Nevertheless, with more Restart schools on the way, districts are increasingly going to have to deal with these kinds of growing pains. But the bigger question is: in a state where rules usually come from the General Assembly and the State Board, how will state education leaders react to this locally-led movement?

“I’m not optimistic that the high-performing school will be rewarded with more flexibility,” Merrill said. “The high-performing school will simply get a growth model that says no matter how good you are, eventually you’re not going to grow. And welcome to the rules of this game.”

Back at Haw River Elementary in Alamance County, students continue to gather once a week to practice yoga poses, create Harry Potter crafts, play basketball with the assistant principal in the gym, and work on robotics. They are hopeful the Restart program will jumpstart their success.

Spending more time with teachers is part of the reason Emily has enjoyed her robotics club so much, she said. Her robotics classmate, Donovan Thaxton, 11, and his friends have enjoyed having something to do while their parents work. So far, they have learned about gears and electronics.

“We picked robotics because we’re smart, and we like doing robot things,” said Donovan, who has built several robots, including a crane and a dog.

“Nobody else (has) built the dog,” Donovan said proudly. “His eyes moved and his tail wagged and everything!”

COMING WEDNESDAY: What is the future of restart schools in North Carolina, and how are they being held accountable? State lawmakers and school leaders weigh in on the new program and where it’s headed.

This story was reported by EducationNC reporter Alex Granados and WRAL reporter Kelly Hinchcliffe through a collaboration funded by the Center for Cooperative Media. EducationNC data reporter Lindsay Carbonell contributed to this report.

Editor’s Note: Gerry Hancock, a co-founder of The Innovation Project, is also one of the founders of EducationNC.