Conclusion

This article is clearly not intended to provide a thorough overview or evaluation of self-governing schools and parental choice. Instead, the more limited – but highly policy relevant – purpose is to draw attention to some of the conflicts between pursuit of those policies and the public interest. Such conflicts arise because of the large and salient individual benefits of education that accrue to individuals relative to the potentially large – but far less salient to individual families or to the operators of individual schools – public benefits that justify the public funding of schools and making it compulsory. The existence of such conflicts need not imply that policymakers should completely avoid policies such as expanded parental choice and school autonomy. Instead, it means that they need to use caution in moving forward with policy initiatives of this type, and to incorporate mechanisms and provisions designed to promote the public interest.

In addition, the provisions might include controls or limits on the exercise of choice by parents to keep schools from becoming more segregated than is consistent with the public interest.

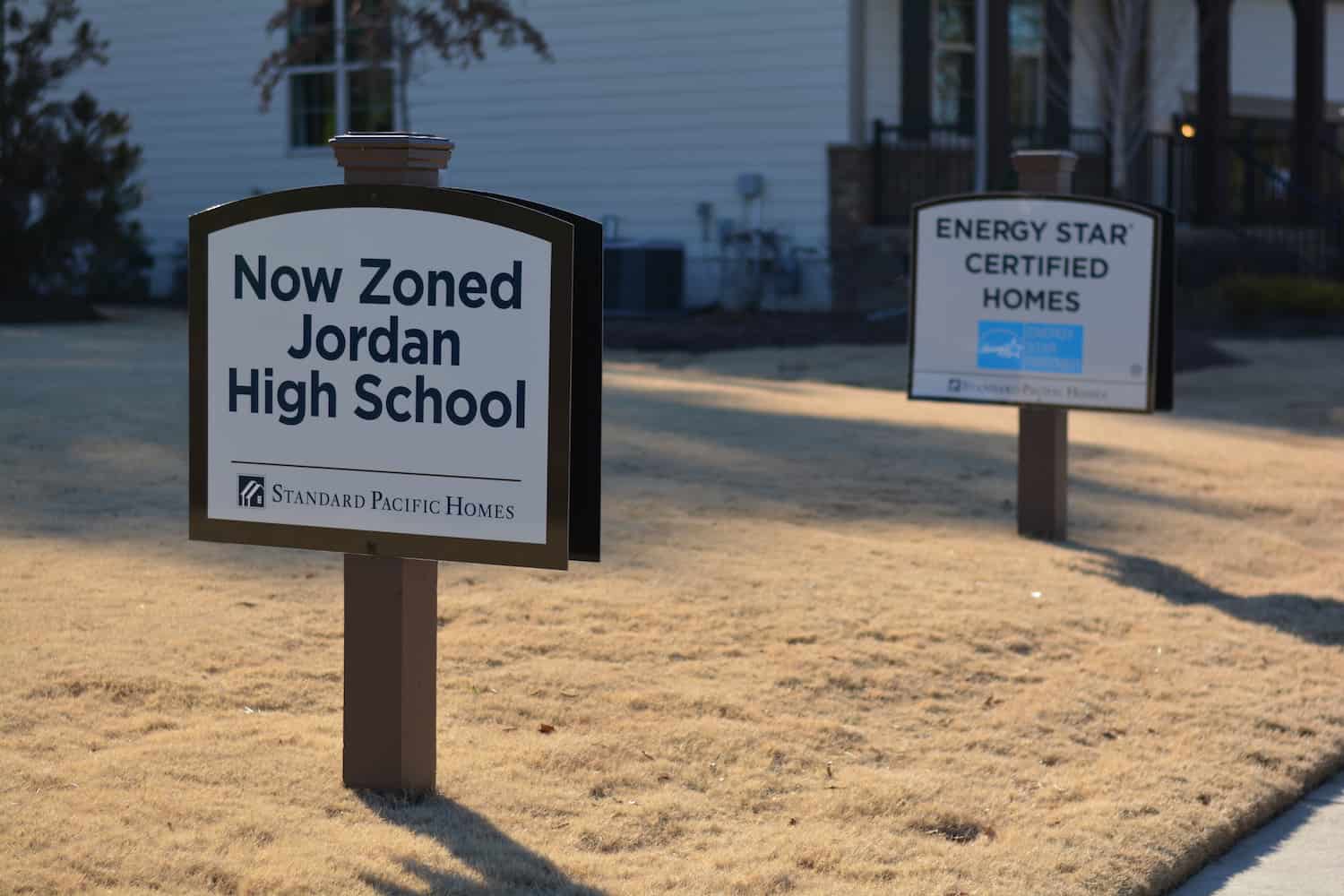

Useful provisions might include, for example, a system-wide accountability program that focuses attention on the internal school process and practices, including admission practices of each school; extra funding and support for schools serving large proportions of disadvantaged students; and district-wide provision of services such as transportation, special education services, and professional development to take advantage of economies of scale. In addition, the provisions might include controls or limits on the exercise of choice by parents to keep schools from becoming more segregated than is consistent with the public interest. In district-based systems in which a higher-level unit authorizes the schools, mechanisms for each district to provide input into the types and locations of new self-governing schools would be desirable. Such mechanisms would help the district foster a single coherent, but flexible, school system that addresses the needs of all the district’s children.

[T]he challenge for education policymakers inclined to move policy in the direction of self-governing schools and expanded parental choice of school is to keep their eyes on the public or collective interest in education.

Although I have not directly discussed voucher programs – that is, programs that provide public funding for privately operated schools – the reader would be correct in inferring that vouchers would generate even greater threats to the public interest than any of the forms of public school choice described here. That follows first because of the extreme difficulty of holding individual schools that are privately owned and operated accountable for public purposes. Many, for example, may not even be willing to report how they spend the public dollars. In addition, depending on the size of the vouchers and the scale of the program, voucher programs may well generate even greater pressures for large concentrations of disadvantaged students. If the program is large, the concentrations may emerge in the traditional public schools. Otherwise, or in addition, they may occur in low-quality private schools established primarily to take advantage of the public funding. Further, given that private schools are likely to refuse to give up their control over whom they accept, what starts out as parental choice among private schools is even more likely to morph into a system in which the schools are choosing which publicly funded students they want to enroll. Finally, any difficulties of the type discussed above associated with getting charter schools to work collaboratively with traditional public schools would undoubtedly be magnified in the context of private schools.

In sum, the challenge for education policymakers inclined to move policy in the direction of self-governing schools and expanded parental choice of school is to keep their eyes on the public or collective interest in education. In the natural pursuit of their own self interests, families and self-governing schools will look out for their own private interests. If the education policymakers do not watch out for the public interest, who will?

Editor’s note: In sharing Professor Ladd’s article with you, it was not the intention of EdNC to cast anyone’s school in a negative light. My son, Hutch Whitman, applied and was accepted to Research Triangle Charter School and he almost went there. It’s a great school. As the principal notes, “[the school has] improved the percentage proficiency across math and biology in one year by 213% for economically disadvantaged students, 106% for African-American students, and 143% for Hispanic students.” EdNC hopes to be able to share the story of the good work this charter school is doing with its students and the community going forward.