|

|

This story first appeared at The 74, a nonprofit news site covering education.

Nationally, school districts and charter schools have poured billions of federal pandemic relief dollars into staffing. Most states don’t detail that spending precisely, but North Carolina does. A FutureEd analysis of how North Carolina is spending its last and largest round of federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief money suggests that localities across the state, especially rural school districts, put larger shares of that money into short-term staffing fixes than into long-term personnel commitments. This decision could potentially ease their fiscal pain when the funds run out.

Of the $3.6 billion the state received in the third and final round of federal relief, about $2.3 billion had been spent or earmarked as of Oct. 31, including $1.2 billion on staffing.

Stressing the short term

Notably, given warnings of looming post-ESSER teacher layoffs, the largest share of North Carolina’s staffing investments — and the single largest last-round expenditure of any sort — went to one-time expenditures.

About 55% of North Carolina’s local education agencies spent some of their third-round ESSER dollars on staff bonuses. That translated to $445 million, or 20% of the final federal installment spent so far. Most of these expenditures occurred in fiscal year 2022, likely reflecting pandemic-related challenges in recruiting and retaining staff.

North Carolina’s state-level data do not show whether bonuses were distributed across the board to thank teachers for their efforts during COVID or targeted to hiring and retention in hard-to-fill areas. But an earlier FutureEd analysis of the nation’s 100 largest school districts’ third-round ESSER plans found that nearly half the districts considering bonuses intended to target them toward specific hard-to-fill positions, hard-to-staff schools or effective teachers. FutureEd’s current analysis of ESSER spending in selected North Carolina school districts revealed that several are using bonuses strategically to hire and keep staff in hard-to-fill jobs. Research has found targeted bonuses to be more effective than across-the-board stipends in attracting and retaining teachers.

Statewide, staff bonuses were most likely in rural areas. “A lot of the more rural districts already face competition (for teachers), especially if they’re bordering a county or a district that is urban and can offer a larger (salary) supplement,” said Rachel Wright-Junio, director of North Carolina’s office of learning recovery and acceleration. “So, I would understand why they would take advantage of awarding bonuses to try to attract and retain teachers.”

Though our analysis suggests that bonuses may have been a wise use of one-time funds, especially when targeted to fill hard-to-staff positions, interviews with North Carolina district leaders suggest that they have also forced some districts to compete for teachers, as some were able to offer higher bonuses than others. Wright-Junio expressed concern that rural districts may see worse teacher and bus driver shortages when the bonus funds run out.

Spending may not equal new hires

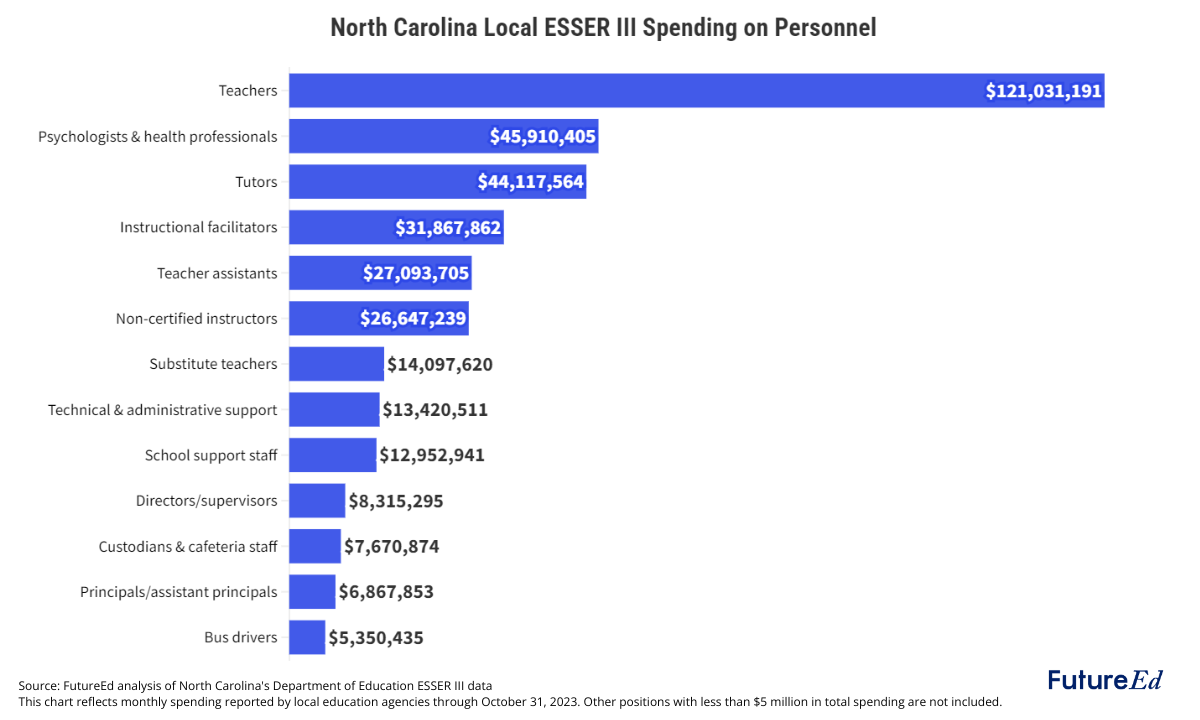

North Carolina districts and charter schools have spent nearly $369.3 million of their final round of ESSER funding on staff salaries, with about one-third of the money going to classroom teachers. An additional $50.2 million went for recurring extra payments to attract and retain highly effective educators. These salary supplements are typically set at the local level and paid for with local funds. Though bonuses represent North Carolina’s largest ESSER expenditure, teacher salaries emerged among the top spending priorities in two-thirds of local education agencies.

We found that the number of North Carolina teachers supported by federal funds rose by 23% between 2018-19 and 2022-23 — an increase of 1,300. But the total number of teachers statewide has declined slightly, by 720, from pre-pandemic levels. This suggests that at least some ESSER money has funded existing educators, not new personnel.

While some districts might be paying existing staff with ESSER dollars to free up other funds, our analysis indicates the statewide student-teacher ratio has declined, from 15.1 in 2018-19 to 14.7 in 2022-23. Pandemic funds may have made it possible for school districts to keep teachers they might otherwise have had to let go due to student enrollment declines.

This doesn’t necessarily mean all these positions will automatically disappear when the ESSER money runs out. “You don’t know the counterfactual, which might be that the district would have hired for that new position anyway and used other spending for it,” said Dan Goldhaber, director of the Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research at the American Institutes for Research and a FutureEd research adviser. “I think it probably indicates that some of those teachers are, in fact, going to go when ESSER disappears. But you don’t know that for sure.”

Looking forward

The North Carolina Department of Education has developed several tools to help local education agencies assess which of their investments are most important to sustain. For example, it created a framework for sustainability, called an investment grid, to help districts use performance data to gauge the value of their investments. State education officials are also helping school districts and charters find additional funding for summer learning, tutoring and other priorities. They developed a strategy for districts to align their ESSER investments with existing federal funding programs so they can potentially transition to other federal funding.

Ultimately, North Carolina’s local education agencies are going to face staffing choices as the deadline for spending the state’s remaining $1.2 billion in federal COVID school aid approaches. Their education leaders have spent the largest share of their last round of ESSER monies on bonuses and other short-term investments may make the task a little easier.