In this article, we use the Cherokee language, followed by the phonetic spelling using English letters, then the full English language translation.

“You want me to walk you to your class because you are in third grade?”

The question was kind, but met with an incredulous gasp from across the aisle. “I’m a big girl,” responded the bus rider, and then, after a pause,“I got Ms. Thurmond.” Then it was the other party’s turn to gasp.

The statement was met with the excitement and squeals, masking the nerves that only a day of firsts can create. “Does she do fun stuff,?” asked the new third grader. The veteran responded, “Yes, a lot. And at the end, at the end of the school year, she’ll do a lot.”

It’s easy to overhear conversations like this on an electric school bus. The usual engine noise is cut to a fraction of its diesel predecessor. Combine the quieter ride with first day of school jitters, and you’ve got three elementary schoolers who don’t have to yell to express themselves.

After riding up hills and highways, down coves, and making impressive two-point turns out of some challenging cul-de-sacs on the Qualla Boundary, this school bus filled with Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indian (EBCI) students was nearing its end destination — Cherokee Central School.

ᏏᏲ, ᏓᏆᏙᎠ (Hello, my name is)

Cherokee Central School (CCS) sits in between the Big Cove and Yellowhill communities of the EBCI. The school was relocated to this new campus in 2009 after a land swap with the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The site reconnects tribal communities and serves kindergarten through 12th grade.

CCS is a tribal-controlled school, operating separate and apart from the Department of Public Instruction. It acts as its own district, and on Aug. 1st, 1990, the Tribal Council authorized the Cherokee School Board, under the P.L. 100-297 Grant for the Bureau of Indian Affairs Department of Education. Beverly Payne, assistant superintendent, said this allows for flexibility, and since all three schools are located on the same campus, it deepens the feel of community.

On the first day of school, buses unloaded students behind the building, while the front is reserved for individual car drop-off. Educators, leadership, tribal council members, and the Principal Chief were all welcoming families. Some staff wore traditional ribbon skirts, while others donned the school colors burgundy and gold or the EBCI seal. There was music and wrist bands, high fives, and many questions being answered.

The carpool lane framing the front of school undulates, reminiscent of the Boundary’s water source, the Oconaluftee River. All three schools — elementary, middle, and high — are connected by this soft stream design, but the curves give each a distinct entry point.

The first stop for the carpool line, and this visit, was Cherokee Elementary. To signal the start of school, a Cherokee language instructor inside recited The Pledge of Allegiance, followed by a chorus of language instructors singing “America the Beautiful,” all in Cherokee. The day’s announcements began, and Assistant Principal Donna Robertson welcomed everyone to their first day.

Robertson talked of rotations, reminders, birthdays, and lunch. She also introduced the Cherokee phrase of the week: ᏏᏲ ᏓᏆᏙᎠ, shi-yo, da-qua-do-a, which translates to “Hello, my name is.” She encouraged everyone to practice everyday. She repeated it again over the intercom, introducing herself.

Robertson ended the morning announcements with this affirmation:

“You’re smart, smarter than you think, and you are loved by all. Always follow the Sacred Path of being responsible, respectful, truthful, and caring to all.”

Consuela ‘Consie’ Girty has been with the district for over 20 years but took the position of superintendent in June of 2023. Girty encourages everyone, even those teachers who aren’t Cherokee, to use all the language they know, even if it is just ᏏᏲ shi-yo, hello, passing in the halls. Her focus, and what she is most excited about, is the cultural immersion opportunity at CCS.

“I’m excited about a lot of our cultural integration, a lot of our language integration. We’ve got a real push on culturally responsive instruction, and I feel like it’s going to make a huge impact with our kids, because that’s what they need, that’s who they are,” Girty said. “And I feel like we have a whole team of people behind that are ready to go.”

ᎭᎴᏫᏍᏓ, Ꮒ, ᎭᏛᏓᏍᏓ (Stop, look, listen)

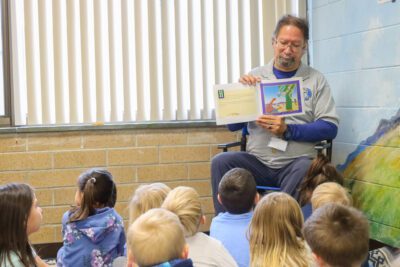

The first moments of first grade can be a lot for any student. Educator Samantha Treadway told her class as they sat down for a story, “It’s okay to be nervous on the first day. Even dinosaurs get nervous!”

She opened up the book, “We Don’t Eat Our Classmates,” where young Penelope Rex has a hard time not tasting her fellow students because they are just too delicious. Students laughed throughout the story, and Treadway took breaks to ask her class how they make new friends.

Once the book was finished, the class was sorted into pairs to talk about their favorite things. Students asked about colors and ice cream flavors. One student exclaimed, “I love my mom and dad, too!” finding common ground with her partner.

After getting to know their new friends, the group stood for a big stretch, and Treadway prepared for their first class outing: a bathroom break. As students sat back on the carpet, she asked student Elvis Crowe to come up and help her.

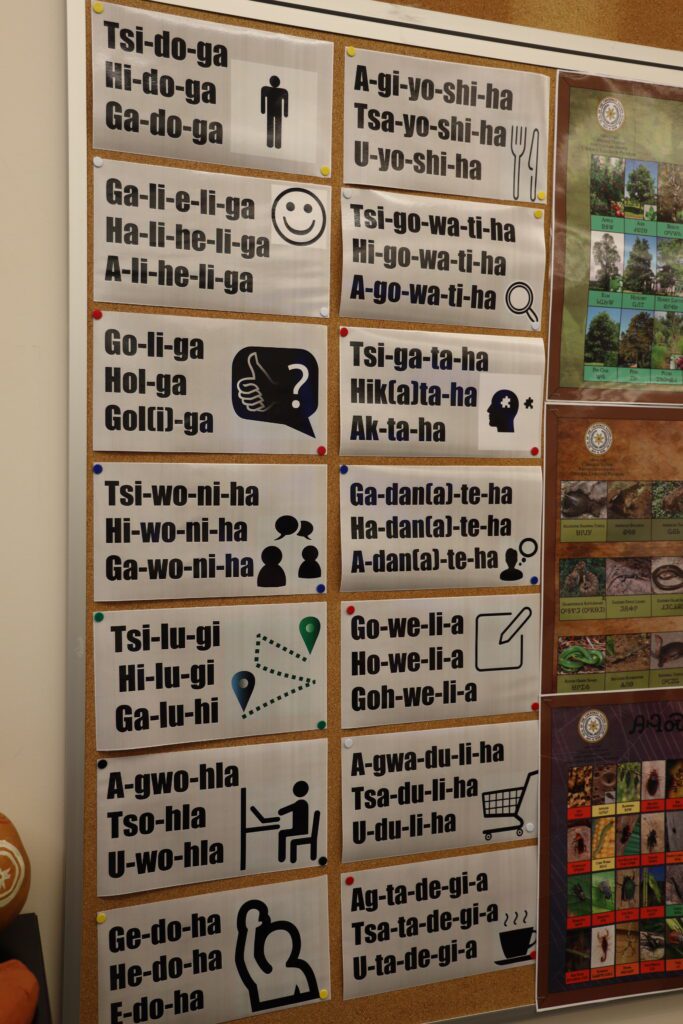

Treadway talked about a phrase in Cherokee they will begin using a lot in the classroom: ᎭᎴᏫᏍᏓ, Ꮒ, ᎭᏛᏓᏍᏓ. The first two words, ᎭᎴᏫᏍᏓ, pronounced ha-le-wi-sda, mean stop, and Ꮒ, pronounced ni, means look, she said to the class.

She then said the word ᎭᏛᏓᏍᏓ, pronounced ha-dv-ga-sta, listen. She said that will be the students’ response — telling themselves and reminding their other classmates to listen. All together — stop, look, and listen.

Crowe knew these words already in Cherokee, so he helped Treadway show the class how to participate. She explained what should happen when they hear her begin the phrase: “Your body should be still, and your eyes should be on me, and your ears should be listening.” Before heading to the bathroom, they stop, look, and listen — ᎭᎴᏫᏍᏓ, Ꮒ, ᎭᏛᏓᏍᏓ — to instructions.

This is the type of seamless integration Girty was speaking about. After the bathroom break, one of the Cherokee language instructors who sang at announcements joined Treadway in the classroom.

In years past, there was a Cherokee language class students would rotate into. The school has shifted to a “co-teaching model,” as Girty calls it. Language teachers are assigned to grade blocks, so they flow in and out of classrooms integrating throughout regular courses all day long.

Heading into Teresa Morgan’s middle school math class, we never had to leave the connected hallways of CCS. Morgan’s seventh graders are friendly with each other and their teacher, already working in groups on a math game. It’s a scene you may expect to see a week into the school year, but not on the first day.

This is one of the benefits of looping, a practice where a teacher moves with a class from grade to grade. Morgan taught these students last year and will see many of them again the next, as she covers sixth, seventh, and eighth grade math.

When inquiring about the continuation of Cherokee immersion for math, Morgan said they focus on basket weaving and beading, native games, and other cultural arts. Those activities incorporate math standards. “Their patterns are math,” she said.

As the seventh graders were leaving for their next class, Morgan told them, “Alright, everybody have a really good day. I will see you in the morning!” Her students replied with jovial farewells, and she responded, “Bye, I love you.” As quickly as the seventh graders left, a new sixth grade class transitioned in. We followed suit with the bell and headed to Cherokee High School.

ᎢᏳᏍᏗᏉ (Bring ’em on)

Richard Bottchenbaugh grew up speaking Cherokee at home.

“It was on both sides of my family. Speakers everywhere,” he said.

At Christmas dinners or holidays, it’s Cherokee at the table. “It’s still that way,” he said. And at his grandfather’s house, “we have what’s called a Cherokee room where no English is allowed.”

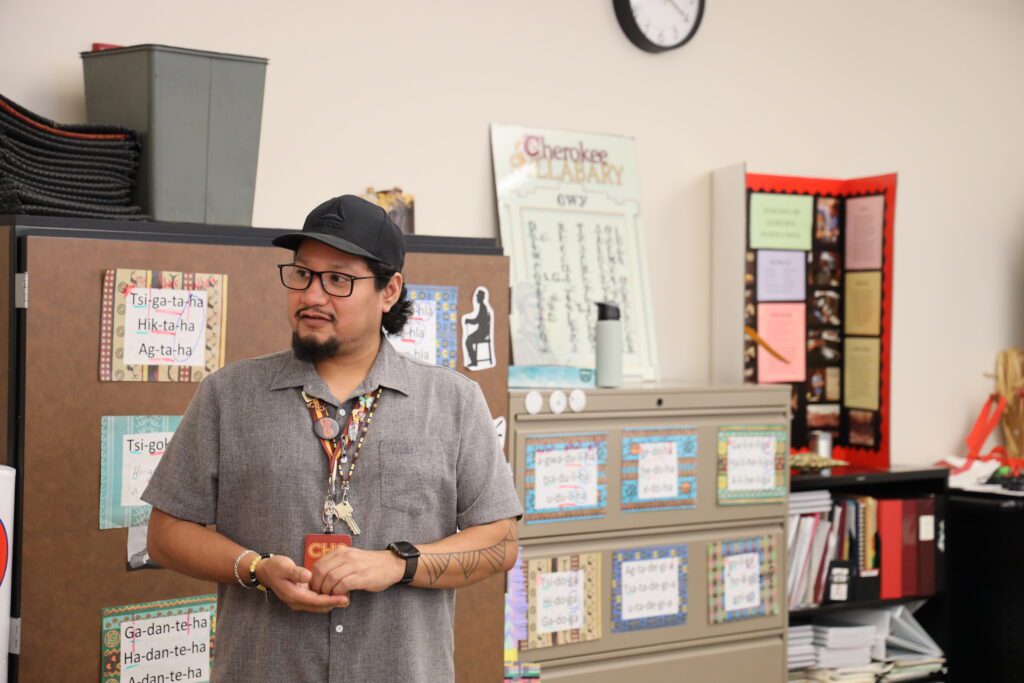

Raised with his native language, Bottchenbaugh was able to build upon this foundation to eventually become a Cherokee language instructor. His teaching career started at the New Kituwah Academy, a full language immersion K-6 school on the Boundary. He moved to CCS six years ago and now teaches three levels of language — Cherokee I, Cherokee II, and Cherokee Immersion — to high schoolers.

The first class is an introductory course where students learn the basics. In Cherokee II, the focus is mastering the syllabary — using it to write, translate, and speak.

This second level is for upperclassmen. Bottchenbaugh is the kind of teacher who believes if he is feeling burnt out, his students are, too. He likes to keep things fresh and give his class creative ways to learn their language.

In the most advanced course, Cherokee Immersion, it’s all about the constant practice of language. Students converse in Cherokee, having to use present, past, and future tenses. They go on nature walks to identify plants, go swimming, dance, sing, and play Cherokee games — all while speaking their native language.

The importance of immersion and dedicated classes to the language cannot be understated. In 2018, the tribe could identify 226 fluent speakers of 16,000 enrolled members.

Bottchenbaugh’s enthusiasm for instruction and his tribe are contagious — a benefit to his students, school, and the survival of the language.

Not far from Bottchenbaugh’s classroom is the wood carving shop, another place where high schoolers can practice a traditional Cherokee art.

Joshua Adams is a successful professional artist and an alumni of CCS, its woodworking class, and its current instructor. This is a popular elective, and one that begins with honoring the past.

CCS’s wood carving class began in the 1930s with the famous Cherokee woodworker, Goingback Chiltoskey. His dedication and instruction inspired many in his community, including his niece Amanda Crowe, who took over his post in 1953. Crowe’s talent and approach to teaching remain the standard at CCS, Adams said. She taught the woodcarving class at the school for over 40 years.

The wood students use to carve is gathered by Adams or donated from the community. Safety is a top priority, and Adams said he believes his students really take that responsibility to heart. Many have carvers at home and are eager to get instruction at school. Along with woodworking, there is a Cherokee arts and crafts course that covers beading, finger weaving, basketry, pottery, and more.

And while it might be a day of firsts, it isn’t the first day of practice for high school sports.

After school let out, the campus was teeming with athletes. On the track, runners stretched. Under the bleachers, cheerleaders got in formation. And on the football field, players ran drills before the coaches started blowing whistles.

There is an upcoming rivalry game for Braves football, and it always occurs at the very beginning of the season. The opponents are not in the conference, and not even within 400 miles of Cherokee Central School.

The Battle of the Nations football game began over 30 years ago and is an annual friendly match up between the Cherokee Braves and the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians’ Choctaw Central Warriors.

Dr. Heath Robertson is the CTE director at CCS and was a football coach for the Braves from 2007 to 2012. He said the contest is important for a myriad of reasons, and one is rooted in tribal culture.

“It’s a way for our young men to show their strength, show their athleticism, show what they’re made out of. And that was the original intent, to really instill cultural pride, pride in who you are as a person, pride in being a Cherokee.”

Dr. Heath Robertson, CTE director at Cherokee Central School

On some football practice jerseys reads the Cherokee phrase, ᎢᏳᏍᏗᏉ, i(e)-yu(you)-sti-gwo. It is a saying past football coach Skooter McCoy brought to the team. It can be interpreted as “bring ’em on,” “bring on all challengers,” and “we will play anyone.”

Elements of the tribe, its past and present, are interwoven through standards taught, through the architecture of campus, through electives offered, and even through the singing of the national anthem. It’s the simple greeting ᏏᏲ shi-yo, echoed in the hallway by young members of the tribe, at school made for them. Its omnipresence is a constant reminder to students of their importance, of their story.

Editor’s note: On August 21st, corrections were made to some phonetic spellings of Cherokee words, and one change made to reflect the EBCI Cherokee dialect versus the Cherokee Nation. If interested in learning more translations, use this language engine.