|

|

Highlights

- The North Carolina House’s budget proposal would change how the state funds subsidized child care. Advocates worry that the change would lead to higher costs for most families receiving assistance.

- The plan also would provide one year’s worth of stabilization funding, at a reduced level. That funding is meant to replace federal pandemic relief, which ends this month.

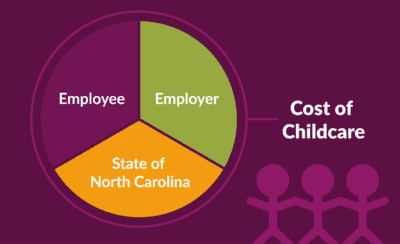

- The proposal includes a one-time $1 million to expand the state’s Tri-Share pilot to three more sites. The pilot splits the cost of child care between businesses, employees, and the state.

The state House released a budget plan Monday that proposes deregulating child care to address a lack of affordable care for families.

It also would provide some short-term relief for child care programs by replacing some of the federal stabilization funds that will run out in less than two weeks. The expiration of that funding, which will happen before any state funding could reach providers, is expected to close some child care programs and increase prices for parents.

The House proposal explains that “deregulatory actions” are among the strategies the state wants to use to address the ongoing crisis in child care. Yet many state officials, national experts, and advocates say the proposal would do the opposite.

The plan would loosen requirements for teacher qualifications, allowing one lead teacher to oversee two classrooms. And it would remove program quality from the equation that determines how much programs receive from the state’s subsidy program.

“It will further destabilize an already unstable child care system,” said Elaine Zukerman, interim director of policy at the NC Early Education Coalition, an advocacy group.

For most families receiving care, the removal of quality from the subsidy payment formula would actually lead to higher costs, according to a statement from the state Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS).

“The House Budget would drastically change the current child care subsidy program,” DHHS said. “Currently, subsidy funds help families afford child care programs with 3 stars or above and religiously sponsored programs that meet health and safety standards. The current budget would allow subsidy payments for any program, regardless of quality. High quality programs — which serve the overwhelming majority of children — will receive less money, making them less accessible by increasing costs for parents.”

In the state’s current system, licensed programs must participate in the state’s QRIS (Quality Rating and Improvement System), and earn three to five stars on its scale, to receive funding from the subsidy program, which uses a mix of federal and state money. The subsidy program is meant to help low-income working families afford care and serves 51,000 children statewide — 8% to 15% of eligible children, according to the state Division of Child Development and Early Education (DCDEE).

The amount of funding providers receive for each child served through the program depends on the county, the facility type, the age of the child, and the program’s star rating.

The budget would remove the star rating factor, which is based on staff education and on program standards. The proposal also says the state does not intend to pay more or less in overall subsidy funding to implement the new rates.

Advocates are concerned this would remove incentives for providers to enhance quality and, in some cases, might lead to lower reimbursement rates, making it harder for providers to offer care to low-income families.

“We strongly oppose this measure, which essentially renders our star rating system — which has been a model for other states across the country — meaningless,” Zukerman said.

Sandy Weathersbee, owner of Providence Preparatory School in Charlotte, who also serves on the boards of the North Carolina Partnership for Children and the Child Care Services Association, said he approves of some of the regulatory reforms the state is working toward within QRIS, but still thinks subsidy rates should reward higher quality ratings.

“In the marketplace, we get to make choices about how we run our businesses,” Weathersbee said. “And if I choose to run a really high-quality business, I want to have a high-quality reward.”

Experts say regulatory requirements are not a major factor contributing to the high cost of child care.

“We’re seeing states and families across the country grapple with the high costs of care,” said Karen Schulman, director of state child care policy at the National Women’s Law Center. “We have seen this discussion of deregulation as supposedly an easy fix. It is most definitely not.”

Not all states require participation in a quality rating system to receive subsidy funding, or differentiate subsidy rates on quality ratings, Schulman said, but the flat rate should add to program’s resources rather than reducing funding.

“It can work if you have everybody feeling good about it, but if you take something away, that’s very different,” she said. “For a program that’s already struggling to make ends meet, it can be very difficult.”

Schulman said overall deregulation has actually led to higher costs in terms of insurance and turnover. The labor-intensive nature of the industry, she said, is the top reason providers cannot pay competitive wages while parents cannot afford to pay more.

“Why it’s so hard to reduce costs for child care is because a lot of it is from labor; it’s the staff,” Schulman said. “But we’re already paying such low wages to staff, you can’t reduce that more if you don’t want to completely reduce the supply even more — lead to an even greater shortage of child care.”

Short-term relief

The House proposal includes $135 million in one-time funding to extend compensation grants to child care providers, but at a reduced rate, for one year in an effort to avoid predicted closures and price increases. The funding should provide 75% of the amount programs are now receiving, legislators and state officials say.

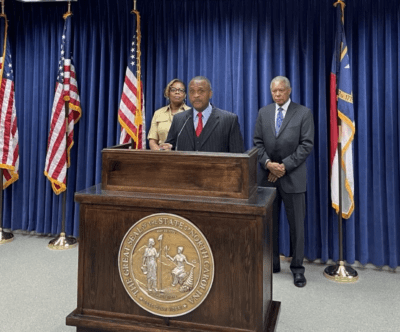

“As we’ve worked diligently on the House budget, one thing has remained clear: We cannot leave Raleigh without addressing the child care crisis,” said budget chair Rep. Donny Lambeth, R-Forsyth. “The House budget continues 75% of current stabilization grants to keep child care centers open, and parents can remain in the workforce, while giving the state time to develop a more sustainable model for child care costs.”

A survey in March estimated the end of stabilization funding would cause about 20% of licensed programs to close within a year, and also would increase tuition costs for parents. Advocates have called for a one-time $300 million allocation this session to avoid that, and Gov. Roy Cooper’s budget plan proposed $200 million.

“It’s great to see legislators recognize and understand that child care is one of the top issues for people across the state of North Carolina right now, and that they absolutely have to do something to address this funding cliff,” Zukerman said. But because the House proposal is short of what’s needed, she said, and because federal funds will run out before it would begin, “there will still be repercussions.”

Sherry Melton, a lobbyist for the NC Licensed Child Care Association, said the funding extension would help “maintain the status quo,” but echoed the need for a long-term solution.

“It’s non-recurring, one-time money, which basically puts us in the same position a year from now,” Melton said. “So we also would like to see both the House and the Senate support additional solutions that last beyond a year.”

The final budget’s components will depend on the House and Senate working together to reach a compromise. Senate leadership has not been publicly supportive so far of spending state money on child care.

“North Carolina cannot afford to wait any longer for legislators to fund compensation grants,” Zukerman said. “This money is going to be gone in less than two weeks. And I know the budget process is complicated and time-consuming, but North Carolina families, businesses, child care providers, and children cannot afford to wait another few months for a budget.”

Long-term solutions

Beyond short-term relief, several visions have emerged for how the state could address the broken child care market. The proposal includes an expansion of Tri-Share, a pilot program that splits the cost of child care between participating businesses, eligible employees, and the state government.

The state started the pilot in three regions in last year’s budget, and it launched in 14 counties this summer.

The House proposal would expand this pilot to three more sites with a one-time allocation of $1 million.

“We are appreciative of the support to the early childhood education (child care) workforce for compensation grants and grateful for the state’s continued trust in NCPC/Smart Start to implement and expand NC Tri-Share in the House’s budget,” said Amy Cubbage, executive director of the North Carolina Partnership for Children, in an emailed statement.

More on Tri-Share

Business leaders have been increasingly vocal about how child care challenges are affecting workforce participation. The N.C. Chamber Foundation last week released a report in partnership with the U.S. Chamber Foundation and NC Child that said the state is losing an estimated $5.65 billion a year because of insufficient child care.

The chamber is looking for a solution that shares costs between multiple entities, according to an emailed statement.

“Our state’s leaders are hard at work negotiating our state’s budget and we trust they will do so with balance, respect, and an eye on maintaining North Carolina’s status as a top state to live and work,” said chamber spokesperson Kate Payne, in an emailed statement. “We recognize the need for a long-term, market-based solution that does not rely on government funding alone.”

Since the pandemic, some states have dedicated permanent state funding streams to help families afford care and help providers pay teachers competitive wages and offer high-quality care and education.

More on other states’ solutions

In North Carolina, advocates have asked the legislature to step in to provide both short-term relief and long-term investment in the form of a subsidy floor, wage supplements and child care provision for early childhood teachers, and investments in Smart Start and NC Pre-K.

Cooper’s budget includes funding for these measures. The House proposal does not.

“North Carolina relies on quality early childhood care and education to support children’s healthy development and learning, allow parents to work and keep businesses running,” the DHHS statement said. “Investments are needed to keep child care programs open, support the workforce, increase subsidy payment rates, and support NC Pre-K. While the House Budget provides some funding for stabilization grants, it does not fully fund the need and does not invest at all in subsidy or NC Pre-K.”

Editor’s Note: This article has been updated to clarify the role of the N.C. Chamber of Commerce and its foundation in the child care policy conversation.