Share this story

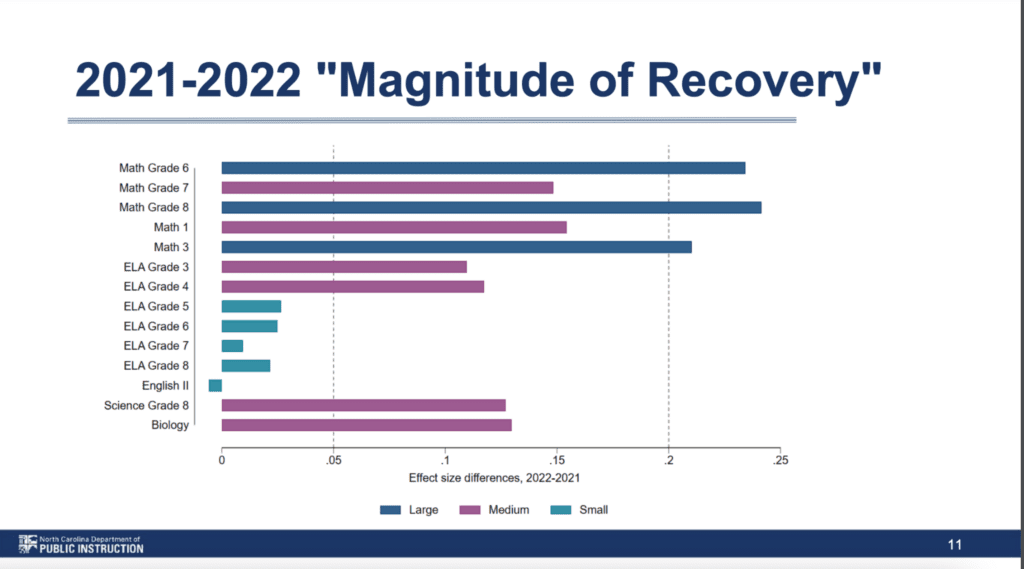

- Students showed signs of academic recovery in nearly all subjects in 2021-22, per the report. The strongest gains were in middle and high school math, with gains also found in third- and fourth-grade reading, eighth-grade science, and high-school biology.

- “What this says to me and says to many of our local level leaders, is that getting kids back into classrooms with their teachers and with their peers... really made a difference for them in math and in science,” DPI's Dr. Jeni Corn said.

North Carolina students made significant strides in pandemic recovery during the 2021-22 school year, the Department of Public Instruction’s (DPI) Dr. Jeni Corn told lawmakers on Tuesday.

Corn, the director of research and evaluation in DPI’s Office of Learning Recovery and Acceleration, presented a new analysis of 2021-22 test results to the House K-12 Education Committee. DPI also released its full 530-page report of that data on Tuesday, which they developed with the Education Value-Added Assessment System, commonly known as EVAAS, a program at SAS.

“We’ve all had these conversations for roughly over a year now about the lost learning, with different people calling it different things,” said Rep. John Torbett, R-Gaston. “We’re more interested currently in the road to recovery, and how do we get our children not only back to where they were, but ahead of where they were prior to Covid? Well, hopefully, we’re going to hear some good news today.”

![]() Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

North Carolina widely saw gains in test scores from the 2020-21 school year, Corn told lawmakers, suggesting recovery from the lost instructional time during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Last year’s 2020-21 report showed “that learning progress had slowed across all grades and subjects, but in some cases, students were as much as 15 months behind where they would have been in a typical year,” per a DPI release announcing the new data.

Students showed signs of academic recovery in nearly every subject in 2021-22, the new analysis shows. The strongest gains were in middle and high school math, Corn said, with notable gains also found in third- and fourth-grade reading, eighth-grade science, and high school Biology. Only high school English (English II) remained unchanged from 2020-21.

“This has been a crisis for our K-12 system. And we have been working so closely, and so many districts and school level leaders have been working so hard to get our kids back on track,” Corn said. “North Carolina is on track – we are in the phase of recovery … What we’re here to talk about today is how the work and the anecdotes we’ve been hearing in the public school system about the work that have been going on during the 2021-22 school year is showing up in empirical evidence.”

‘Our schools and districts have made incredible strides’

The analyses from both 2020-21 and 2021-22 compare test scores projected for individual students against their actual scores. Those projected scores come from 2018-19 testing data – what Corn said offers “a picture of business as usual.”

As a reminder, North Carolina suspended end-of-grade and end-of-course tests during the 2019-20 school year due to the pandemic.

The new report found “higher percentages of students with more positive ‘effect sizes’ or results when compared to the 2020-21 findings,” the DPI release said, showing that “greater proportions of students are showing more positive gains.”

Effect Sizes: Standardized metric that indicates magnitude or practical significance of a research outcome. A large effect size means that a research finding has practical significance, while a small effect size indicates limited practical applications.

DPI’s pandemic-recovery presentation

Here is how DPI categorized effect sizes:

- Small: Effect size less than 0.05

- Medium: Effect size ranges from 0.05 to 0.20

- Large: Effect size greater than 0.20

The report also found the amount of time at the end of the 2021-22 school year needed to recover lost instructional time also varied by student group, grade, and subject.

In some grades and subjects, recovery time decreased by almost half, the report shows. The 15 months needed for recovery in Math 1 after 2020-21, for example, decreased to nine months after 2021-22. In sixth-grade math, the 10 months needed was reduced to less than five months after 2021-22; the 14.5 months of recovery time needed in biology was cut to 8.25 months.

“The results from the 2021-22 school year empirically confirm what we’ve been hearing from teachers and principals and parents around the state,” State Superintendent Catherine Truitt said in the DPI release. “Our schools and districts have made incredible strides in helping so many of our students get back on track to their pre-pandemic performance. This data also tells us there is more work to be done and fortunately we still have federal funding available to support interventions targeted at the students who need it most.”

DPI highlighted several other findings from the data:

- There were smaller effects of growth in middle-grade reading scores.

- In 2021-22, on average, students identified as economically disadvantaged underperformed projected scores compared to the general student population for all tested subjects, except eighth-grade reading. However, the magnitude of recovery for students identified as economically disadvantaged was greater for reading in grades 3, 4, and 5 compared to the general student population.

- On average, at the state level, students across all races and ethnicities (American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian/Pacific Islander, Black, Hispanic, Two or More, White) showed signs of academic recovery for every subject, with the exception of Asian students in reading for grades 3, 4, and 5; Black students in reading for grades 6 and 7 and English II; Hispanic students in reading for grade 7; and white students in English II.

- On average, students with disabilities’ actual scores for 2022 were closer to predicted than the general student population. The same was true with multilingual learners.

- Overall, N.C. public school students showed greatest gains from 2020-21 to 2021-22 in middle and high school math.

“What this says to me and says to many of our local level leaders, is that getting kids back into classrooms with their teachers and with their peers – really getting that hands-on – really made a difference for them in math and in science,” Corn said. “And in ELA – (we’re) still headed in the right direction, but less of a jump.”

Moving forward, ESSER funds, truancy, and more

The new report can help leaders understand the long-term impact of the pandemic on students, Corn said, and help identify future interventions. Disaggregating the data by specific student demographics also helps state and local leaders offer targeted interventions, she said.

Previously, this data influenced investments in academic bridge programs, which provided summer programs to help elementary students who were in kindergarten through fourth grades during the 2019-20 school year. The data also informed middle-grade math interventions, she said, and Career and Technical Education supports.

“Our school leaders and our students still have work to do, but we are headed in the right direction,” Corn said. “Students are being helped to get back on track to where they were expected to have been if the pandemic never happened. And fortunately, we still have ESSER dollars that our local school districts are using to target these interventions to students where they need them most.”

As districts work to allocate their remaining Covid relief funds, a national report released last month found North Carolina is among 15 states expected to take the “biggest hit” as ESSER funds expire in 2024. (You can read more about that “ESSER cliff” here.)

Rep. Hugh Blackwell, R-Burke, asked if DPI can measure where students are now in relation to where students would have been if the pandemic had not happened. Corn said DPI is working with EVAAS to develop such a “year-to-year” model that would measure when the state’s districts “have recovered.” DPI hopes to release such a report by this summer, she said.

Rep. Marcia Morey, D-Durham, asked about recent truancy data showing that upward of 30% of students are chronically absent. According to 2021 myFutureNC data, 26% of K-12 students missed 10% or more of school days. The state’s 2030 goal is 11%.

Corn said local districts are using various “intentional strategies” to keep students in class.

“We’ve been hearing the same things about the number of students identified as chronically absent,” Corn said. “We all know that in order to learn, students need to be in school.”

While chronic absenteeism is still a problem, things are moving in the right direction, Corn told lawmakers. The number of students identified as chronically absent increased from 22.6% of the tested student population in 2020-21 to 28.5% in 2021-22, the report says.

Corn said many districts have seen improvement during the 2022-23 school year.

For those chronically absent students, the new DPI report showed academic recovery from the pandemic in reading for grades 3, 4 and 5. However, those students “fell further behind the general student population in 2021-22, especially in Science Grade 8 and Biology; and Math in Grades 5, 6, 7, 8, and NC Math 1 and 3,” per the release.

Rep. Brian Biggs, R-Randolph, asked if DPI had studied the difference in learning recovery between schools that reopened for in-person instruction early, versus those which remained in remote instruction.

DPI’s new report includes an analysis that categorizes every school by the number of remote days they had for the 2020-21 and 2021-22 school years, Corn said. (You can view that data starting on page 146 of DPI’s full report.)

Anecdotally, Corn said DPI heard that schools that reopened earlier, particularly in western N.C., saw smaller test score decreases in 2020-21. However, she said that 2021-22 data shows the rest of the state catching up.

“(Covid) certainly has had a significant impact on the cohort of students that were in school during that 2021 school year. We don’t know, I don’t think, fully what the longitudinal impact is going to be on these students,” Corn said.

As a state, Corn said DPI is keeping 2018 test scores “front and center.”

“I think we’d all admit, we had a lot of work to do in 2018, too – that there were students that we were failing in 2018,” she said. “But I think that part of the intent of this analysis and this research is keeping that 2018 idea at least on the table, and then thinking about how we can help kids, not just get back to that point, but beyond.”

Recommended reading