Senate President Pro Tempore Phil Berger, R-Guilford, listed child care as one of the top challenges facing state legislators in this year’s long session during his opening remarks last month.

“How we deal with those challenges will impact the North Carolina we leave to our children and grandchildren,” Berger said, mentioning child care alongside education, infrastructure needs, and health care.

As federal funds propping up the child care industry ended last year, legislators pointed to the 2025 session as an opportunity to find a long-term solution that alleviates high prices for parents, labor shortages for businesses, and low compensation for child care teachers.

“Obviously the issues that we had last session are still issues,” said Rep. David Willis, R-Union, a co-chair of the early childhood legislative caucus last session and owner of a child care program in Charlotte. “This session, they’ve not necessarily gotten any better. I think we’ve gotten more awareness. I think we’ve gotten some more urgency around it, which is going to be helpful.”

But how much the state allocates to solve these issues will depend on the state’s larger fiscal picture, Willis said.

“We’ve been told to kind of prepare for a really tight budget with Western North Carolina and all the recovery there,” he said. “Having extra dollars is going to be a challenge, but I think we’re also at a point where we can’t backslide any further on early childhood.”

The caucus, which has not yet announced its chairs for this session, is trying to find policies that increase the supply of child care, lower the cost for parents, and maintain quality.

Advocates call these three realms — access, affordability, and quality — the child care “trilemma.” Several early childhood advocacy groups will release their shared agenda in the coming weeks.

Sen. Jay Chaudhuri, D-Wake, a caucus co-chair last session, said addressing these issues will depend on whether the state finds a dedicated funding stream for early childhood programs.

“That’ll be one of the key budget questions that lawmakers need to ask, is whether we’re willing to make a down payment on our our young people’s future,” Chaudhuri said.

Who should pay?

Legislators probably will consider policies this session that split the cost of care among multiple entities.

Parents, employers, and the state should contribute, Willis said.

“There’s an obligation there for the state to step in,” he said. “The question, at that point, is: How much can we do? How much should we do? And that’s where we’ve obviously had some disagreement over the years, and continue to do so today.”

Tri-Share, a pilot launched in 2024 and created in 2023 legislation, does just that: splits the cost of child care between participating employers, eligible employees, and the state. But participation is voluntary and has been growing slowly, program leaders said.

Smart Start is recommending the legislature either make the program permanent or expand it. Lt. Gov. Rachel Hunt’s package of policy priorities said she will “lead a coalition of business leaders, families and policymakers to make child care more affordable by renewing and expanding” the program.

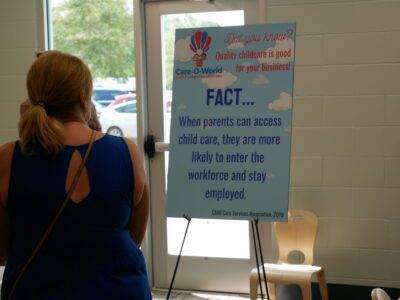

Figuring out how businesses can engage in child care solutions is the job of Samantha Cole, who holds a new role created by the Department of Commerce in 2024: the state’s first child care business liaison. Though businesses of all kinds and sizes have multiple options to help employees afford and access care, state investment is still necessary, Cole said in January at a legislative advocacy day in Boone.

Sen. Jim Burgin, R-Harnett, a caucus co-chair last session, said every level of government — local, state, and federal — needs to chip in.

Several local initiatives have started across the state to raise awareness on the importance of child care and convene local stakeholders to create solutions. Some local governments have contributed funds to those solutions.

Other states and localities have created public-private partnership funds, programs that match local funds with state investments, trust funds, and new taxes — from businesses’ payrolls to properties to gambling.

At the federal level, Burgin said a block-grant approach to education funding could benefit early learning. He also said he thinks Medicaid funds should be able to fund community college tuition and child care for student-parents enrolled in the program.

How should the funding be spent?

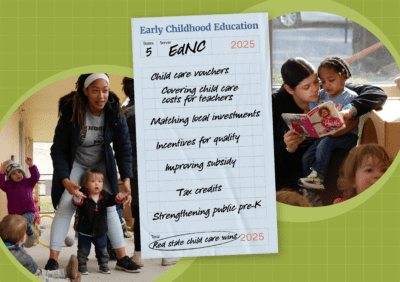

However much funding comes from the state, legislators will consider policies this session that provide support to programs, teachers, parents, and the state’s early childhood system. Here are the policy ideas at play:

To save existing programs and open new ones

The legislature will decide this session whether to continue funding compensation grants that go directly to licensed programs. These grants, started through federal dollars, were meant to stabilize child care coming out of the pandemic. Advocates warned that 20% of programs would close within a year if that funding stopped.

The state legislature allocated $67.5 million in June and $33.75 million in November to continue the grants, at 75% of previous funding levels, through March.

Instead of experiencing mass closures, the state has had a slow leak of programs. From February 2020 to November 2024, the state experienced a net loss of 5.6% of its licensed programs.

Willis said he hopes the state continues some form of direct support to providers.

“I don’t want to give too much hope for that continuing, because the idea was that we would really be off of it by now, but I also can’t see us walking away and losing more ground, because it would be extremely difficult to make that up in some other way,” he said.

As Western North Carolina recovers from Hurricane Helene, local leaders say more funding is needed to rebuild affected child care programs and help families access care as they return to work. The legislature gave the NC Partnership for Children $10 million for child care relief in its second relief bill in October.

Caucus members have backed funding for a statewide subsidy floor in recent sessions, and advocates from Smart Start and NC Child are recommending the policy again this session.

A subsidy floor rate would establish a minimum amount that child care programs across the state would receive for serving children through the state’s subsidy program. Right now, subsidy rates vary widely from county to county. They are based on what programs charge, which, experts say, is not an accurate indicator of actual cost.

A floor rate would help sustain programs in lower-income and rural areas. Low subsidy reimbursement rates were the main reason six programs closed in Western North Carolina in the fall of 2023, the programs’ operators said.

Increased funding for NC Pre-K, the state’s pre-K program for at-risk 4-year-olds, is a recurring request from advocates. Legislators in recent sessions have not increased funding to sufficiently cover the costs of administering the program, providers say. Private child care programs, public schools, and Head Start programs host NC Pre-K classrooms.

Legislators also might consider policies that expand access through start-up funding, tax breaks, partnerships with institutions that have unused facilities, and streamlined regulations.

Burgin said property tax cuts could help people interested in starting home-based child care programs. House Bill 115, filed in February by Democratic legislators, would totally exclude licensed child care facilities from property taxes.

Burgin also said he is meeting with community college presidents, state administrators, and county commissioners to find vacant or underused facilities that could house private child care programs and cover some facility costs. Regulations should be streamlined to remove barriers to these partnerships, he said.

“If we could deal with the property and the expenses, then I think it changes everything,” Burgin said.

To recruit and retain teachers

Legislators will consider how to support and strengthen the early childhood teacher workforce, from higher compensation and benefits for current teachers to pipeline-building strategies for future generations.

Stabilization grants have mainly been used to increase teacher compensation in the form of base wage increases, bonuses, and benefits.

Willis said he plans to propose legislation that would give automatic subsidy eligibility to child care teachers, which would help teachers pay for child care for their own children. This has proven to be an effective retainment tool in Kentucky and several other states.

“The more we can do to support those teachers who are also mothers, the better,” Willis said. “And we can keep them in the workforce longer and take some of the pressure off the providers, then it’s a win-win for all of us.”

Advocates also have asked in previous sessions for funding to expand WAGE$ statewide. Housed at the nonprofit Early Years, the WAGE$ program offers education-based supplements to educators who commit to staying at a child care program.

Kristi Snuggs, president of Early Years, told EdNC the program has cut turnover by more than half over the last 30 years.

Community colleges train the majority of early childhood educators. Hunt’s plan prioritizes creating incentives and securing funding for community colleges to host on-site programs that serve as learning labs for prospective teachers and provide care for students and communities.

Pre-apprenticeships and apprenticeships in early childhood education have also spread in popularity across the state in the last couple of years through the work of Building Bright Futures, an initiative from the North Carolina Business Committee for Education that has grant funding through September 2025. The effort provides financial support and resources to encourage new teachers to enter the profession.

To help parents afford care

Legislators will consider proposals to help parents afford child care, which is difficult across income brackets. A recent analysis from the National Women’s Law Center found that a family in North Carolina must make an average of $156,200 annually to comfortably afford infant care, defined as spending 7% of a family’s income.

The largest source of funding for helping families afford care is the state’s subsidy program, funded through a mix of federal and state dollars.

Legislators might consider increasing funding to expand the reach of the program, which is aimed at helping low-income working parents afford care.

Tri-Share, the cost-sharing pilot program for employees of participating companies, is another tool aimed at increasing affordability. It is intended to help parents who make too much to get subsidy assistance but still struggle to afford care. Families must make less than 300% of the federal poverty line to qualify.

Legislators allocated $900,000 over two years in 2023 to three regional Smart Start partnerships, which act as facilitator hubs to sign up businesses and manage payments to child care providers.

The program is opening participation to any interested employer this year. As of February, it was serving only 18 employers, 20 employees, and nine children. The funding could reach about 300 children, said Mary Scott, director of strategic partnerships at the North Carolina Partnership for Children.

Burgin and Willis said they are still learning about lessons from the pilot.

To support early childhood infrastructure

Smart Start is asking for $15 million in additional recurring funds to “improve the quality and increase the accessibility and affordability of early care and education, expand infant and maternal health programs, and support parents as the first and primary caregivers.”

Smart Start is a network of 75 local partnerships, which are nonprofits that support young children, families, and teachers through programming, subsidy distribution, technical assistance to child care programs, and a variety of other initiatives and resources.

The organization is also requesting a 10% administrative rate to administer NC Pre-K, a recurring $5 million for Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library, “long-term solutions for early childhood teachers” including WAGE$ expansion and health care coverage, increased behavioral support, the reduction of suspensions and expulsions in early childhood settings, and several of the items mentioned above: a subsidy floor rate, NC Pre-K investments, and Tri-Share funding.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this article misstated the number of employers participating in Tri-Share.