|

|

This article is part of a book by EdNC titled, “North Carolina’s Choice: Why our public schools matter.”

Here is a free PDF of the book. A printed copy can be ordered here.

North Canton Elementary in Haywood County only runs one morning bus route, and at the wheel is Carol Harkins. She has been a bus driver for 25 years.

“I like building those relationships with these kids, and just seeing how they get so comfortable with you, that sometimes they call you mama, and just being able to give them time to talk,” she says. “These are my kids.”

In 2021, Tropical Depression Fred dumped 14 inches of rain in 12 hours, triggering flash floods and landslides in Haywood communities, and Harkins was behind the wheel of a school bus. She recalls crossing a bridge to drop off some students, and not five minutes later, turning around and seeing that the bridge was starting to go.

She called in for support, and she, along with the rest of the students, were lifted via a bucket truck across the water. Asked if any of her students were scared, she said no, “We played games. We made it fun.”

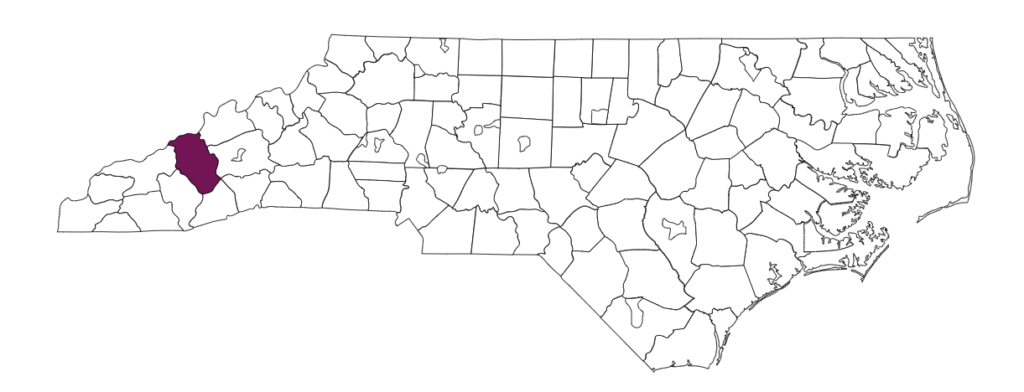

This flooding was just one of the many challenges Haywood County and its school district have had to overcome. In the last decade, the district 30 minutes west of Asheville has persevered through a cyber attack, multiple flooding events, a pandemic, and most recently, the closing of the county’s largest employer.

The Canton paper mill provided well-paying jobs for more than a century to local residents. The loss shook the foundation of Canton, as well as the county in which the town sits.

And while the community wrestles with the idea of what will come next for their economy, the public school system remains a constant — inherently connected to the community, offering refuge during challenging times, and creating fertile grounds for growth.

Our public school systems fall in the special category of anchor institutions. Anchor institutions are rooted by definition, moored to the communities they serve. In North Carolina’s rural regions, they offer stability and support when the environment inevitably changes.

Anchor institutions are the first line of defense in times of crisis. When a 100-year flood hits, or a town’s largest employer shuts its doors, or life comes to a halt during a pandemic, communities head to the anchor institutions to assess, organize, mobilize, and cope — to share their burdens.

“The anchor institution concept idealizes the belief in the power of place-based institutions to support social and economic growth,” says Michael Harris and Karri Holley, who study the impact colleges have on the economic and social development of cities. School districts often have an even bigger impact on towns, cities, and counties.

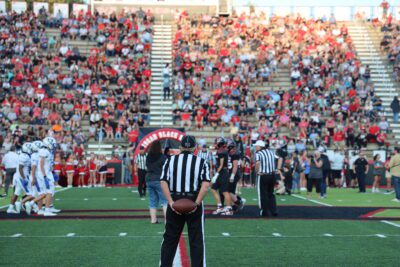

As spiritual as a Sunday service can be, so too can a Friday night under the lights at a high school football field. Generations of families who have sat in the same pew at church will sit on the same bleacher during the Pisgah vs. Tuscola football game in Haywood County. The rivalry between the two high schools began in 1922 and is locally known as The Mill vs. The Hill.

Pisgah High School is within eyesight of the Canton paper mill, which shut down in 2023 after over a century of business. Tuscola High School, as you can imagine, rests on top of a hill about eight miles west in Waynesville.

Jill Mann is the principal of North Canton Elementary. In the wake of the Canton mill closure, she said, “I don’t know that there’s another school system that has had so many things happen to them that we have. And it just seems like everybody comes together, and we get through it every single time.”

Dr. Trevor Putnam took the Haywood County superintendent job in November 2022. Five months later, and still on the heels of the COVID-19 pandemic, he was at the helm when the paper mill announced its closure. Relying on the community’s history of resilience, Putnam chose to be hopeful.

“It’s looking at the glass half full or half empty,” he says. “And I choose to look at it half full, and an opportunity to fill it. Whatever the end result may be, we’re going to be OK, and we’re going to be Haywood Strong.”

School districts are the safety nets for our state and our society.

Social prosperity takes center stage

What is social prosperity and how can it be measured? According to researchers Katharina Lima de Miranda and Dennis K. Snower, social prosperity is determined by solidarity, agency, and empowerment. When we talk about it in schools, it can look like belonging and being given a safe space to grow.

Each of these things — solidarity, agency, and empowerment — starts with taking risks. It happens when students begin making friends at school. It continues during all-district band competitions or try outs for the junior varsity basketball team. Building blocks for social prosperity are found in so many places at school.

With solidarity comes comfort with oneself and within a group and the experience of belonging. Feeling connected, students are more likely to cheer on their peers.

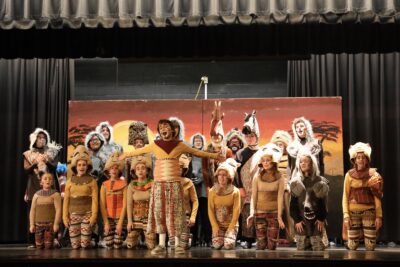

An easy place to see and sense this type of belonging is through the arts.

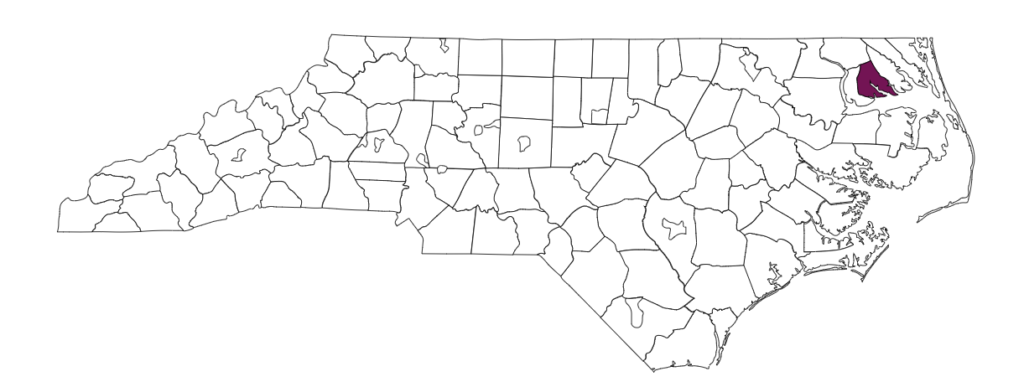

Angela Martin has been teaching theater for 18 years in the Clinton City and Sampson County school systems. Sampson County is the state’s largest producer of turkeys and sweet potatoes, and 49% of the county acreage is taken up by farms.

Martin grew up performing at the Sampson Community Theater and brings her lifelong love of the stage to the region’s students with seasonal all-county productions. The theater teacher prioritizes representation for these plays, getting a substitute for herself and traveling to all the high schools to hold auditions. She has an open call and makes sure the home school community is involved. The spring 2023 all-county performance of “Grease” included 40 students from eight high schools as well as homeschool students. Every performance sold out.

“Just like in the original movie, the girls are very close and they love each other as family, and we’re kind of like that,” one student said.

Simon Ussery is a homeschool student and snagged the lead role of Danny Zuko. On stage with all his new friends, Ussery said Martin “encourages and pushes us to be better.” His supporting cast, both on and off the stage, nodded their heads and cheered in agreement.

“Theater education can help young people develop a strong sense of self and identity, build empathy and learning among peers, and broaden the ways they make meaning of the world around them,” say Gwynne Middleton and Mary Dell’Erba of the Education Commission of the States.

During a production, students take agency in their jobs — whether it be starring as the lead role or creating a new world through set design. They are individually empowered while working in unison with their crew. And as the whole cast takes center stage at the end of a show, is there a bigger sign of solidarity than a final bow, hand-in-hand? In theater, each student has a supporting role working toward a common goal. An unanticipated benefit is increased social prosperity.

The weaving of a community safety net

In 1946, President Harry Truman signed into law the National School Lunch Act, with hopes to “safeguard the health and well-being of the nation’s children and to encourage the domestic consumption of nutritious agricultural commodities and other foods.” Of the many programs birthed from this Act, the one we are most familiar with today is the National School Lunch Program, more colloquially known as free or reduced price lunch.

From August 2022 to February 2023, not even a full school year, over 2.1 billion free or reduced price lunches were served in our nation’s school systems. In our rural communities where food is often grown, food insecurity remains high. Access to food is influenced by population density and geography. Fewer people to serve means less grocery stores, and the distance to these food hubs means more money for gas and potential transportation barriers.

While schools are not grocery stores, they are spaces where students come with provided transportation five days a week. The communal meeting space lends itself to learning and feeding kids. More than lunch, schools can offer an array of food initiatives, such as the School Breakfast Program, Summer Food Service Program, and the Child and Adult Food Care Program.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, an estimated one in every five children in North Carolina struggled with hunger, and almost 60% of students enrolled in North Carolina’s public schools qualified for free or reduced price school meals. And in March 2020, federal pandemic regulatory waivers allowed schools to offer free meals to all. This expansion of the program highlighted the importance of schools in our society, again making the case that they serve as anchor institutions.

Kim Cullipher is the school nutrition director at Perquimans County Schools. Perquimans is considered 100% rural by the North Carolina Department of Commerce. Cullipher says, “Universal feeding allowed me to know that no child that attended school went hungry that day. That’s our purpose. That is why we show up every single day, fighting daily uphill battles that get harder each day; our purpose, our why, is to ensure that no child goes hungry.”

Feeding students remains top of mind for many school districts as they wade through the choppy waters of a post-pandemic world. No Kid Hungry says, “Longitudinal data suggest that children’s learning outcomes suffer when they regularly experience hunger and that nearly every aspect of physical and mental function is hurt as well. Food insecurity affects concentration, memory, mood, and motor skills, all of which a child needs to be able to be successful in school.”

Rural school buildings are especially positioned to be intermediaries within the health and wellness space. In addition to nutrition, school counselors, social workers, and nurses provide comprehensive student support services to support the whole child. These services are provided to all students, including those served across 18 exceptional children programs: intellectual disability, visual impairment, hearing impairment, traumatic brain injury, serious emotional disabilities, developmental delays, learning disabilities, orthopedic impairment, speech/ language impairment, autism, other health impairments, and multiple disabilities.

In some school districts, this includes dental care.

According to the Health Resources and Services Administration of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, as of September 2019, an estimated 2.4 million North Carolinians struggled to get adequate dental care. Only 25% of dentists in North Carolina practice in rural areas.

Montgomery County is one of our 78 rural counties and is one of the regions designated as a Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) by the North Carolina Office of Rural Health. In an effort to mitigate that shortage, the county school district started working with a local health care provider to deliver dental care on school campuses.

In 2017, two school-based dental centers opened at East Middle School and West Middle School with the help of FirstHealth of the Carolinas, a nonprofit health care network headquartered in Pinehurst.

FirstHealth received grant funding for the construction, planning, and implementation of the two clinics. When school is in session, the clinics often are open two to three times a week, serving students from all grades. During the summer, dental services continue with parent-scheduled appointments.

Dr. Paul Hood of FirstHealth Dental says having the clinics in schools eliminates any transportation issue for parents. The caretaker doesn’t have to leave a job to transport the student, so there isn’t a missed day of work.

Another barrier to entry for many health care providers is trust. If the family doesn’t have a history of going to the dentist for preventive care, appointments can be scary. The school environment is familiar, taking the element of the unknown out of the equation.

Hood says, “There’s not that much availability of places for our parents to take their kids for dental care, and I think they feel good about it being at a school. That gives us (and them) a little sense of validation. And I think they feel safe about bringing them up there at the school.”

Adding to the school district dental services, in October 2022, FirstHealth started a portable clinic program, which visits all six Montgomery County elementary schools and the high school.

“I think the portable program again helps tremendously with eliminating the transportation barrier,” Hood said. “Kids actually can miss less school time by seeing us in school. They don’t have to come to school late or leave early. Oftentimes, we find that the day they have a dental appointment, they simply don’t go to school at all, whereas if we’re with the portable program, we’re taking them out of class for maybe 30 or 45 minutes.”

During the 2022-23 school year, the portable clinic had 244 elementary student visits, 1,271 middle school student visits, and 159 high school student visits. School-age children are getting regular teeth cleanings, learning preventive care, and creating the healthy habit of seeing a dentist. None of this could happen without the support and excitement of the school district, Hood says.

Partnerships among community organizations like these are win-wins. Using the strength and expertise of the dental clinic along with the space and school’s ability to organize (and always pivot) makes for a healthier student body.

The people of anchor institutions

In our rural areas, anchor institutions are there for the highs and lows, but mostly for everything in between. They both ground communities when the earth below them feels unsteady, and in times of smooth sailing, they stand just as firm. There doesn’t have to be a crisis for an anchor institution to play a role.

Schools and the people in them are anchor institutions in the small but gigantic act of showing up every day — in the math teacher refusing to let a student give up, in the bus driver greeting their riders the same way each day, in the support of teammates when the game winning shot is missed, or in the euphoria of watching the scoreboard hit zero when the home team is victorious.

The day-in and day-out of choosing to try and having staff create the opportunity for students to fail and learn and grow is the daily work of our public school system.

In the COVID-19 pandemic, we saw the immediate need for schools and the tireless work of leadership trying to make it safe for students to return in-person. The U.S. Department of Education collected data before and during the COVID-19 pandemic and determined “that in-person learning, on the whole, leads to better academic outcomes, greater levels of student engagement, higher rates of attendance, and better social and emotional well-being, and ensures access to critical school services and extracurricular activities when compared to remote learning.”

All public schools are anchor institutions for their communities, but in rural areas it hits harder. Generations of families drive the same roads, attend the same church, and play on the same football fields — the roots in rural regions run deep. Anchor institutions in these areas thrive in spite of constant challenges because of the people who inhabit them.

Behind the Story

Caroline Parker did the reporting and shot the footage for the Sampson County theater short. Laura Browne produced and edited the video.