In his book, “A Secular Age,” philosopher Charles Taylor makes the point that our contemporary Western society never engages in what he calls “anti-structure”— that is, a deliberate break from the time-bound business of what most of us refer to as the “daily grind.” We may take the occasional vacation, but, for the most part, we moderns are the proverbial hamsters on a wheel, seldom taking the opportunity to escape as a society from time and its demands on our minds and bodies.

However, I would argue that for the first time since the Enlightenment’s emphases on science, human freedom, and free market competition led to pervasive secularity some 500 years ago, the entire world was forced into a form of “anti-structure” in 2020-21 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This is no small occurrence. Not only did the world economy virtually stop for a short period, but all of us stopped the routines of our daily lives — the hamster climbed off the wheel, if you will — to adjust to a new reality forced upon us by a virus.

What we had not counted on was just how reliant we had become on our routines of daily life to give meaning to our existence. In this sense, the loss of employment and the meaning it gives to our lives as well as the loss of face-to-face communication and interaction with our fellow human beings led to a worldwide identity crisis. Who were we without the activities of daily life, and what was our purpose?

The American community college has not been immune to the effects of this crisis, especially since its own identity as a sector is tied closely to enhancing individual students’ social and economic mobility. Ours is a very people-centric enterprise. The teaching and learning that occur on our campuses are individualized by necessity and design. Many of our students, and indeed our faculty and staff, choose our colleges primarily because we are humane — we care about them as individual human beings — something that requires us to maintain a physical presence with each other as intrinsically social beings. We may believe in and market our missions as economic development engines, but what the pandemic has taught us at the community college is that the core of our mission is to bring higher education to individual human beings in a personalized manner.

While some of us were fortunate enough to keep our jobs through the use of today’s video conferencing platforms, many others — chiefly among them our community college students — were not so fortunate. Their jobs required time spent face-to-face with customers in the hospitality and food services industry, which declined 26% in overall employment in Beaufort County between July 2019 and July 2020. Moreover, as community colleges such as my own largely altered their instructional and co-curricular modalities to online education out of necessity, students lost their traditional classroom connections with faculty, staff, and peers.

Not only were these individuals often displaced from their work due to the dangers of a deadly pandemic, they were also displaced from an educational experience that represents hope for a better future in a ruthlessly competitive economy. Suddenly, in a matter of weeks in March 2020, the foundations of individual identity in 21st century life — work, school, family, even religion — collapsed into an ephemeral, virtual heap left smoldering on a host of websites. The degree of psychic distress can best be described as the first true, global, existential crisis in the modern world.

At community colleges, as with our colleagues in the PK-12 and university sectors, we took the necessary measures to keep our students, faculty, and staff safe. We told ourselves that our traditional strengths in reaching students “where they are” meant we could continue to meet our mission of access and student success in a virtual fashion. We told ourselves that we might lose enrollment due to a chronic lack of broadband service for the rural and inner-city poor, but that we could at least count on tuition and fee assistance from the federal and state governments to enable those who lost their jobs to continue with their higher education experiences. For example, we could (and did) spend significant sums on purchasing laptops, tablets, and hot spots with cellular plans to mitigate internet access in our remote rural areas, such as the four-county, 2,100 square mile region my college serves.

But, despite all of these hopeful assumptions, we were wrong. Many of our students did not persist. Our enrollment at Beaufort dropped over 10% between fall semester 2019 and fall semester 2020.

An April 4, 2021, article in The Chronicle of Higher Education indicates that community college enrollments have declined nationally close to 10%, compared to a 4.5% decline in other higher education sectors. What accounts for this large disparity?

Certainly, the loss of employment stemming from the pandemic accounts for some of this decline among community colleges. When you cannot afford to pay for rent, food, transportation, childcare, and health care, higher education takes a back seat. Also, a lack of access to, experience with, and competency with distance learning technologies led to some students withdrawing from their studies.

However, I would like to add one additional reason, which the 2020 IPEDS Data Feedback Report for my college made very obvious: Many of our students, at least at Beaufort, prefer an in-person learning experience. This report made plain in stark statistical terms that our students, when compared to students at our peer colleges, take fewer online courses. In fact, 46% took no online courses at all in fall 2019, compared to 28% for our peer institutions. And, these numbers come from a college that truly excels at distance education, employing more Blackboard Exemplary Course Award winners than any college or university in North Carolina.

The fact of the matter is that no matter how successful we become in offering distance learning, we cannot replace the support and camaraderie that our students feel in traditional, face-to-face courses. Nor do our students feel the same sense of accountability for their words and actions online as they do in-person. We have to face reality: Online instruction is only as good as technology enables it to be, and our current technology cannot successfully replicate the experience of interacting in-person with a faculty member and other students.

So, even amidst all the rhetoric about the evolving prevalence of and necessity for distance education in our technologized, interconnected world, is it possible that we have it wrong? Do we need to pay closer attention to the learning styles of our students, who, after all are why we exist in the first place and who will always vote with their feet?

As the president of a rural community college that serves a diverse variety of students, let me pose the heretical proposition that in-person interaction carries distinctive meaning, even in today’s internet-saturated world. The students from my four-county region in far eastern North Carolina want their community college experience to build on the social bonds that tie them to their cultural identities — those that proceed from family, friends, and geography.

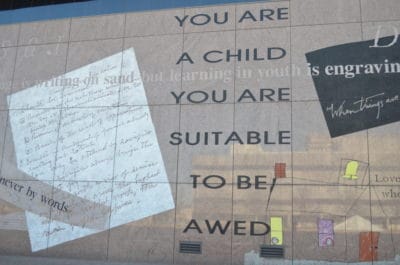

Essentially, by waiting for in-person class sections before returning to campus, they are telling us that they wish to create the individual connections that come from literally breathing the same air and inhabiting the same space in time as their peers. They are reminding us of the importance of place as a physical, geographical space imbued with the meanings of identity gleaned from live, in-person interaction with faculty, staff, and peers.

Perhaps this is the real meaning of “community” in our sector — a meaning that cannot be replicated in online instruction, which still lacks the substance, vitality, and sense of personal responsibility associated with direct human interaction. At Beaufort, we intend to remember that lesson as we move into the post-pandemic world, where, hopefully, we can rediscover our common humanity face-to-face.